This is the third part of an Exedra series on race in Piedmont. The murder of George Floyd in May sparked significant activism throughout the country, and led Marta Symkowick (PHS 2020) to pursue these local stories. Part I focused on Sidney Dearing, the first Black homeowner in Piedmont, who was driven out of town by white residents and the city government. Part II delved more deeply into the history and causes of residential segregation in Piedmont, and suggested housing policy changes that could further diversify the city.

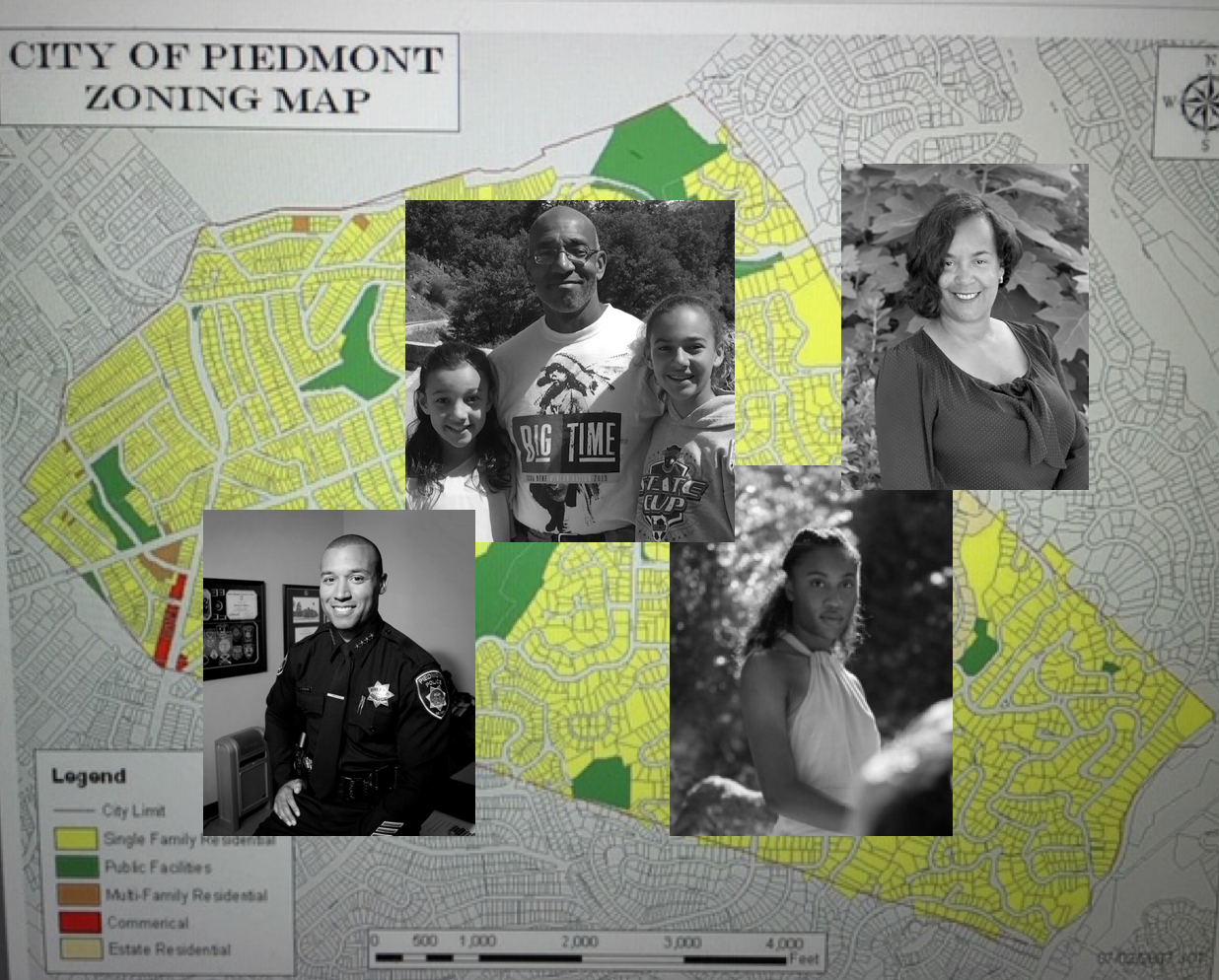

Part III presents the views of several Black members of the community, including residents (one of whom was just elected as the first Black member of the Board of Education), a student at Millennium High School, and the city’s police chief. Their perspectives show how far Piedmont has come since 1925, when, after ferocious, racist harassment, Sidney Dearing finally sold his house — but also how much more work needs to be done.

Current perspectives on race in Piedmont

Piedmont has diversified somewhat since Dearing’s time, when the population was almost 98% white. In the 2010 census, 72% of residents were white, 18% Asian, 4% of Hispanic origin (which can be of any race), 1% Black, and 5% multiple race. Oakland, by contrast, is one of the most diverse cities in the United States, with 2010 census figures of 36% white, 27% Hispanic, 24% Black, 16% Asian, and 7% multiple race. Where does Piedmont go from here?

Veronica Thigpen

Veronica Thigpen moved to Piedmont two years ago as her daughter prepared to start high school. At first she was uncertain about what it would be like to settle in a predominantly white neighborhood, but so far she has found PADC and the broader community to be extremely welcoming.

“I joined PADC because I was looking for a community of people who would have shared values,” Thigpen said. “I hit the jackpot there. We also met neighbors that are just the loveliest family. They’re really good friends of ours now. That’s really all anyone can ask for when you move to a new community. You want to make friends.”

Yet Thigpen still considers it important to have honest conversations about the history of a community like Piedmont. “There are certain stories that we just don’t tell in this country, and this is what we have been learning about ever since George Floyd’s murder,” she said. Dearing’s treatment by white Piedmont is one of those “uncomfortable truths.”

“It wasn’t surprising to me as a Black American. I’ve heard stories like this my whole life. The story of Piedmont is full, layered, textured. And I think that it’s important that we tell all of it right.”

She continued: “It’s really important for Piedmont, and cities across the country as a whole, to learn about, talk about and remember what has happened so that we can deal with what’s going on now and create a better future.”

Thigpen ran for and won a school board seat in November. In addition to her goals of promoting educational excellence and student involvement in decision-making, she also plans to further develop the racial equity policy the Piedmont Unified School District adopted this year. The policy focuses on creating an anti-racist curriculum, increasing teacher diversity, making the PUSD culture more inclusive, and hiring a new staff person to coordinate implementation of the policy across the district.

Richard Turner

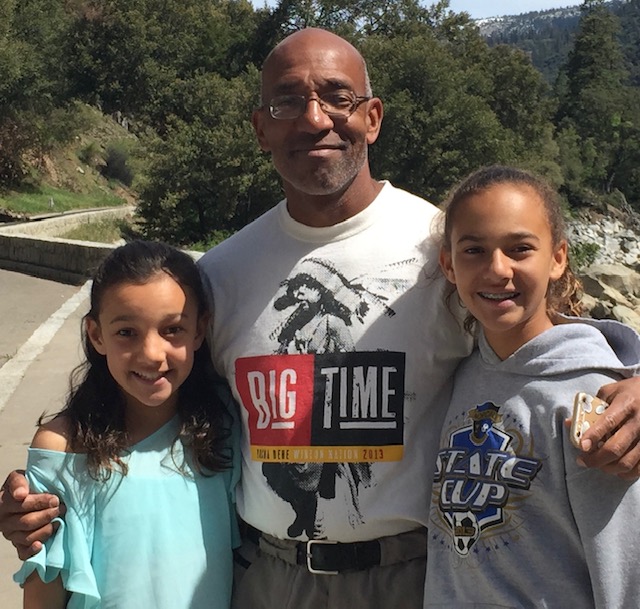

Piedmont resident Richard Turner has lived in Piedmont since 2002. He raised his son and two daughters in Piedmont and said his children were perceived differently by their classmates, in many cases based on longstanding stereotypes.

“I have to believe that at some level, their engagement with these groups has been impacted by the fact that they’re African American,” he said. “They have had issues about their hair and their features and all these things that are definitely held in less esteem.”

Turner still remembers listening to a conversation between two young boys when he was playing tennis at Hampton Park.

“There was a Black kid playing with this white kid,” he said. “The Black kid had fire red hair. You wouldn’t be confused that he was African American, but he was fair-skinned. At one point during their interaction, he said to the white boy, ‘You have that good hair.’ And I cringed because I thought we were beyond that. “

The situation can be especially difficult for his daughters because they are biracial (Turner’s son is not biracial). “Their mother is Caucasian, and I’m African American, so they always had to deal with these identity issues,” Turner said. “And I have to tell you, I don’t think that Piedmont makes that particularly easy for them.”

Turner reflected on one of his daughters’ experiences at PUSD. She’d asked a teacher why he was leaving Piedmont, and he cited a lack of diversity. “So, this was a white teacher. And he asked her, ‘Can you imagine being African American in this community?’ He didn’t realize she is African American. There’s that kind of confusion or challenge that they have to deal with.”

Participating in activities outside Piedmont has had a meaningful impact on Turner’s daughters’ upbringing. Their East Bay United soccer club teams, for example, Turner characterized as racially and culturally diverse. “I think that had a huge impact on their socializing,” he said.

Turner was clear-eyed about the contradictions inherent in Sidney Dearing’s story. “The thing that impressed me the most about his story was that it was so well documented, because there’s no denying what that was all about, ” he said.

Yet he was also struck by how Dearing’s story is essentially absent from Piedmont’s recounting of its past, and that this absence of Black history extends to other underrepresented groups as well. The website of the Piedmont Historical Society, he noted, includes nothing about Dearing and little about other people of color.

“What happened to the Ohlone Indians, that segment of the history, took up a paragraph. That was a violent history that they just didn’t [fully tell],” he said.

Despite all of this, Turner said he has found the Piedmont community earnest in its willingness to participate in remedying this past. He initially joined the Piedmont Anti-Racism and Diversity Committee to model activism for his children. PADC’s founding mission is to “promote and practice inclusiveness, foster an appreciation of differences, and raise global awareness within Piedmont and surrounding communities,” according to its website.

Turner has since taken on more responsibility, becoming the PADC school liaison. In this role, he has met many people in the community committed to racial equity and inclusion. And when he’s asked others to get involved in PADC activities, he has always received positive responses.

“Sometimes all you need to do is ask,” he said. “People are so gifted in this community and they’re so willing to get engaged.”

However, as in the rest of the US, Turner still sees racism perpetuated in part by an inability to listen. Issues like white privilege, housing affordability, and reparations for past injustice, such as Dearing’s case, are ever present in Piedmont as elsewhere in the country.

“I think sometimes people don’t hear each other,” he said. “There has been a long-standing need for open communication in order to make Piedmont an anti-racist place, but having the conversation is not going to be easy. ”

Turner considers further acknowledgement of the problem across the wider community to be a vital first step.

Harmonee Ross

Harmonee Ross is a senior at Millennium High School and president of the Black Student Union. She lives in Richmond but has spent countless hours over the past year trying to understand Black history in Piedmont. So far, it has been a difficult process. “As a Black person in the Piedmont community, I feel very alone even though I have BSU,” she said. “I know freshman year I gave in to the racism that I was receiving by not reporting it,” she said. “I didn’t know how to report it. I didn’t know how to tell.”

Despite this, she was excited to learn about Sidney Dearing. “His story made me feel that I wasn’t the first person to experience racism in Piedmont,” she said. “Mr. Dearing’s story is so important because if I had learned about his story freshman year when I joined Piedmont schools, I would have felt so empowered to know that he stood his ground. He didn’t give in. And that’s powerful. But I would actually love to learn about his story in school, because I believe it’s important to have it in the curriculum so citizens of Piedmont can understand [their history].”

At the same time, Dearing’s story highlights some persistent truths about racism. “Wealth can’t get a person of color the same respect that a white person can get. And that is something that white privilege blocks white people everywhere from seeing, and it’s heartbreaking and it’s frustrating but it’s something that needs to be changed,” she said.

“I constantly use the phrase, you got to look at the man in the mirror, look at yourself, see what you can do besides using your wealth. Wealth in Piedmont is used as a pacifier: ‘Oh, you donated money. You did good.’ But I don’t think that’s true. You have to change the way you look at others. You have to stop calling the police on Black students who are just trying to get home or trying to get to a friend or exploring the city that they go to school in.”

Ross said that when BSU first started last year, she joined for a community she could connect with in a way she could not with her white peers. Through BSU she found the strength to speak up. This year, as president, she is hoping to expand the purpose of BSU in the Piedmont community. “We are a school-based club and we are our own community. First of all, we’re there to have fun, to be kids, to bond, to love on one another, and to get to know each other and our struggles. Now, we’ve also taken the position of sharing our stories and taking action.”

BSU recently produced a video containing their experiences at PHS and participated in a panel discussion led by the Piedmont Educational Foundation. BSU members are excited to see new policies adopted by the community, including the Board of Education’s new racial equity policy, and hope to continue to spark conversation in Piedmont, Ross said.

Ross has also become involved with other groups in Piedmont, including the new Youth Anti-Racism Project, where she helped organize two recent events. Ross was also asked to become the Millennium High School liaison for PADC. She makes a monthly report to the PADC Board about race relations at the school.

“I was completely shocked when Dr. Turner asked me to take on that role,” she said. “And not because it’s the biggest position in the world, but because I look at that club, that committee of adults as my inspiration. There are people in that club that make me feel proud to be Black. They make me proud of all the work that I’m doing.”

Jeremy Bowers

Piedmont Chief of Police Jeremy Bowers lives in Oakland, and his children attend Piedmont schools. He appreciates being a part of both communities. “Living in Oakland has been fantastic,” he said. “I’ve told this to many different people, and sometimes they get emotional about it, but I have never lived in a place where I felt more comfortable, individually, as being who I am and what my racial background is. I can walk around Oakland with my children, and we just blend in. There are other people that look like us. We don’t get second looks.”

But the Dearing case made an impact on Bowers. “Everyone in the town of Piedmont, from the residents, to the police chief, to the members of the government seemed to be against Dearing,” he said. “I was just absolutely appalled, and very disturbed reading that history.”

Since starting his job four years ago, Bowers has had many conversations with Piedmont residents. “In Piedmont, over the last four years as chief I have heard a number of perspectives about the experience of folks who live in Piedmont. Just the feelings, the emotions [surrounding] living in Piedmont when you’re a person of color [make more sense after] hearing that history.”

Bowers said that working in Piedmont has been extremely positive. “I feel very fortunate to work here from the standpoint that at this time in our country’s history, we’re going through a reckoning. I think there are a lot of people who are engaged in and interested in what’s going on, interested in seeing, and being a part of a conversation and actions of reform and change. Not just in policing, but I think across a number of different areas and perspectives of our society.”

Seeds of change

In July, a group of anonymous high school students, also inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and troubled by things they have seen and heard in the community, launched an Instagram account, @reportingracismpiedmont, to expose racist behavior. The group seeks to illuminate the experiences of people of color in the Piedmont Unified School District and, “to use data to paint a bigger picture of how commonly racist incidents occur in PUSD and what the responses are.”

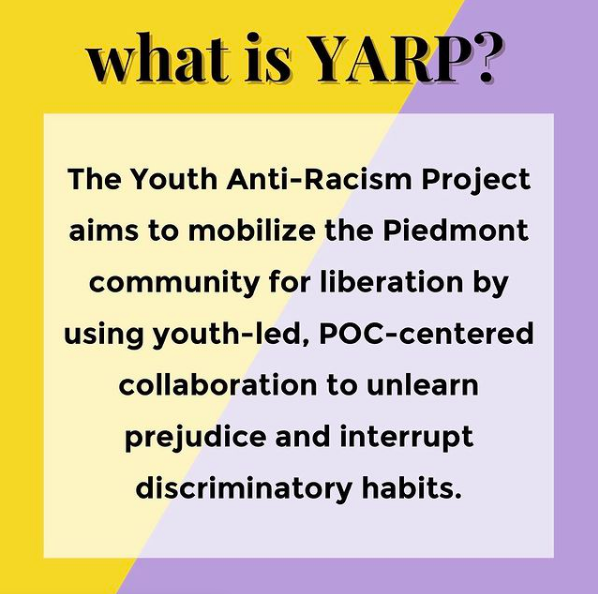

Several other groups are also addressing race in the school system. The Youth Anti-Racism Project “aims to mobilize the Piedmont community for liberation by using youth-led, people of color-centered collaboration to unlearn prejudice and interrupt discriminatory habits,” according to its website. POPS (Piedmont for Oakland Public Schools) is dedicated to bridging the educational divide between Piedmont and Oakland schools by supporting Oakland organizations that fight for educational equity, according to its mission statement. And one of the Piedmont Racial Equity Campaign’s four subcommittees focuses on education and promoting equity and inclusion in the school district. (Three other subcommittees address housing/zoning, policing, and diversifying the city.)

Since passing the racial equity policy in June, Piedmont’s school district has continued to work on issues of racial justice and inclusion. The Board of Education in July unanimously approved a resolution condemning institutional and systemic racism, after consulting with many different community groups.

Before her election to the school board, Thigpen worked with the board through PADC. She said the resolution is a good start, and that the next step is to make policy.

“You have to envision where you want to go and figure out how you want to get there, and then make a plan for the steps that you’re going to do to achieve those goals.”

The school board has also begun to discuss expanding the interdistrict transfer policy, which would allow additional students from more diverse communities outside Piedmont to attend PUSD schools.

A new focus

In early August, the City of Piedmont took a huge step forward by voting for a formal repudiation of racism. In a unanimous decision, the city council committed to review city policies, procedures, ordinances, values, goals, and missions “through an anti-racism lens.” Councilmember Tim Rood said an important aspect of the resolution is “examining and owning” the city’s history. Rood hopes to build on the resolution and would like to see a plaque or other memorial near the Dearing residence.

“It’s important that we all understand what happened so we can appropriately respond to the effects of historic injustices around race that are still apparent in our community,” he said.

Councilmember Jen Cavenaugh would also like to see the city continue to take action. “I hope this resolution is the first step of many,” she said.

Some of the biggest changes have come from within the Piedmont Police Department. Bowers has prioritized improved officer training that includes educating every department employee about the Dearing story and the role the city’s police played. (The police chief at the time was a local Ku Klux Klan leader.) Bowers has also instructed officers to communicate more comprehensively in interactions with the public.

“At the end of every contact, the officers are doing two things,” he said. “Explaining why they’re making the stop by voicing their rationale, basis, and the conclusion of the call, and ensuring that the person understands [the call] by asking if they have any questions or concerns about the nature of the stop.”

Bowers has also worked with the city council to review and change some of the Police Department’s use of force policy. Rood approached Bowers after hearing a speech by President Obama addressing police reform. Over the summer, the 8 Can’t Wait campaign proposed eight reforms police departments across the country could implement immediately, including eliminating chokeholds and banning officers from shooting at moving vehicles.

“I got in touch with the chief to request a briefing on those eight specific aspects of use of force policy,” Rood said. “The chief actually decided to eliminate the use of one of the force-hold maneuvers that has resulted in some of the tragic loss of life at the hands of police officers.”

Shortly after the murder of George Floyd, Bowers decided to immediately suspend the use of force that was authorized in that case, the carotid hold.

“It’s not a chokehold per se in that it restricts blood flow under very specific dangerous situations where an officer is in essence fighting for their life,” he said. “But, given the totality of the circumstances where we’re at, and just the need to take a break and look introspectively and allow us to have some time to really be self-reflective in terms of the policies and use of force policies, I chose to suspend that policy.”

Bowers is currently working with the California Attorney General and a group of African American police chiefs throughout the state to advocate for increased historical training.

“When we send people out to police communities [without] having an understanding of the history of the region, we set ourselves up for disaster,” he said. “Without an understanding of the history, you don’t know where you come from, you don’t know where the culture of the area you’re policing comes from, you don’t understand past pains that may still persist to this day.”

After learning about Dearing, Bowers also feels a responsibility as chief of police to try to promote reconciliation in the community.

“[The history is] important because we need to acknowledge the past wrongs of communities and organizations we’re a part of. I take that seriously as a police chief,” he said. “I think reconciliation is important, even though obviously, I wasn’t a part of this organization 100 years ago. As the leader of it now, I still represent the organization and all that it was, is and will be.”

In addition to acknowledging the past, Bowers considers reconciliation to include an apology by the department for its role in racist behavior, a vow to do better going forward, and a formal process to make good on that vow.

Wonderful to hear about the Dearing story! Although the part about his experiences in Piedmont with the KKK were not so wonderul. The details are so meaningful in many ways and should be memorialized for sure! A plaque is an excellent suggestion! We are so devoid of an accurate history of being black in Piedmont and that should change. I almost thought my family’s experience was a “first” for Piedmont! Little did I know…until now!

I am a 47 year old black woman who attended Beach Elementary School, PMS and PHS and graduated in 1994. I don’t know of any other PHS alums who are black and can say the same for a 12 year stint.

I am currently writing a book partially on my experiences growing up black in Piedmont. I currently live in LA but visit my father Reginald E. Mitchell (Black Piedmont home owner, 1978-1999) frequently, who relocated from Piedmont to Oakland hills after I graduated from PHS. Would love to be involved to share my experiences any time.

Appreciative of this important and informative series about living while Black in Piedmont. I am a 33 year resident, Black Woman and raised my 31 year old Daughter who is also Black. I would like to share our experiences.