Many Piedmonters are surprised, if not shocked, when they hear the story of Sidney Dearing, the first Black homeowner in Piedmont. In 1924, Piedmont residents and city government leaders, all white, conspired to force Dearing out of town. Although open hatred has greatly diminished over the past 100 years, the legacy of racism and white privilege live on today in Piedmont’s zoning and real estate practices. There are glimmers of hope for developing a more diverse, inclusive community through housing and zoning policy reform, but they will require significant adaptation on the part of current and future Piedmont residents.

Persistent lack of diversity despite limited demographic progress

Dearing was forced to sell his house in 1925. Some five years later, the 1930 census counted just over 9,000 residents in Piedmont. The demographic breakdown at the time was 98% white, 1.5% Asian and a scant 0.5% Black – around 40 residents. In 2010, the year of the most recent census, the city’s total population of just under 11,000 was 71% white, 17% Asian, 4% of Hispanic origin (reporting of this category started in 1970), 5% “multiple race”, and 1% Black – around 144 people. While the increase in Asian residents is certainly a shift from a century ago, Piedmont has remained overwhelmingly white.

By contrast, Oakland, which surrounds Piedmont geographically, is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the United States. In 2010, Oakland’s population was 36% white, 26% Latino, 24% Black, and 16% Asian.

De facto and de jure segregation

How has Piedmont, which was incorporated in 1907, continued to be an enclave of sameness amid a sea of diversity? The violent, blatantly racist practices that forced Dearing out of the city are a thing of the past. But the demographic figures mentioned above nonetheless paint a picture of stark contrast between Piedmont and its neighbors.

In his 2017 book “The Color of Law”, Richard Rothstein, senior fellow at the Haas Institute at UC Berkeley, documents the complicity of all levels of government in maintaining racist housing policy up to the present day.

“Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation [also known as de facto segregation]… but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States [also known as de jure segregation]. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time.”

Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law,” (pages vii-viii)

Rothstein doesn’t mention Piedmont specifically in his book, but uses nearby Milpitas to illustrate a point that could certainly apply to city government in Dearing’s time: “The Milpitas story [from the mid-1950s] illustrates the extraordinary creativity that government officials at all levels displayed when they were motivated to prevent the movement of African Americans into white neighborhoods. It wasn’t only the large-scale federal programs of public housing and mortgage finance that created de jure segregation. Hundreds if not thousands of smaller acts of government contributed. They included petty actions like… discovering that a road leading to African American homes was “private” (page 122).

Rothstein also cites numerous other examples of local governments throughout the country in the post-World War II period of rapid suburbanization condemning or re-zoning property to “prevent African Americans from residing there.” These municipalities include Richmond, CA, Swarthmore, PA, Deerfield, IL, and St. Louis County, MO (pages 123-25).

In Dearing’s case, after Piedmont residents failed to drive him out by violent means, city leaders sued to take his property by eminent domain. Piedmont dropped the lawsuit after Dearing agreed to sell his house, but this episode shows how official government action accompanied popular prejudice in keeping Blacks out of Piedmont almost a century ago. According to Piedmont City Council member and professional city planner Tim Rood, the legacy of these practices persists. “Segregation is still very much present in the way our cities and suburbs are organized,” he said.

Piedmont Housing and Zoning History

The origin story Piedmont likes to tell about itself goes as follows: The 1906 earthquake led many wealthy families to move from San Francisco to Oakland and Piedmont (which was at the time an unincorporated area in Alameda County). These families created a close-knit community that has over time nurtured a small-town lifestyle with high property values and good schools, always set apart, since Piedmont’s incorporation in 1907, from the surrounding big city of Oakland. This particular story is documented in the website of The Piedmont Historical Society.

Yet like many small American towns, Piedmont’s “official” history hides a dark underbelly of exclusion. This history progressed through several stages, from outright segregation by means of racial violence in the 1920s; exclusionary single-family zoning starting in the 1920s; racial restrictions and redlining in the 1930s and 1940s; and recently, the more subtle practices of real estate “pocket sales.” Echoing much of the rest of suburban America, these persistent exclusionary practices have made it extremely difficult for anyone but wealthy white (and, more recently, Asian) people to enjoy the high property values and good schools Piedmont offers.

Irene Cheng, Professor of Architectural History at the California College of the Arts, is also a Piedmont resident and the co-chair of the housing/zoning subcommittee of the recently formed Piedmont Racial Equity Campaign. PREC’s mission is to raise public awareness of race and diversity issues in Piedmont and to advocate for policy changes in support of a more diverse city.

According to Cheng, “In neighborhoods [like Piedmont], big landowners bought up large tracts and then developed them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” Often the communities would be advertised as exclusively white. “That was part of the marketing appeal”, Cheng said. “[The neighborhood] was advertised as advantageous because white families could move into these neighborhoods and be assured that they wouldn’t have to mix with other races. Their property values would remain stable.”

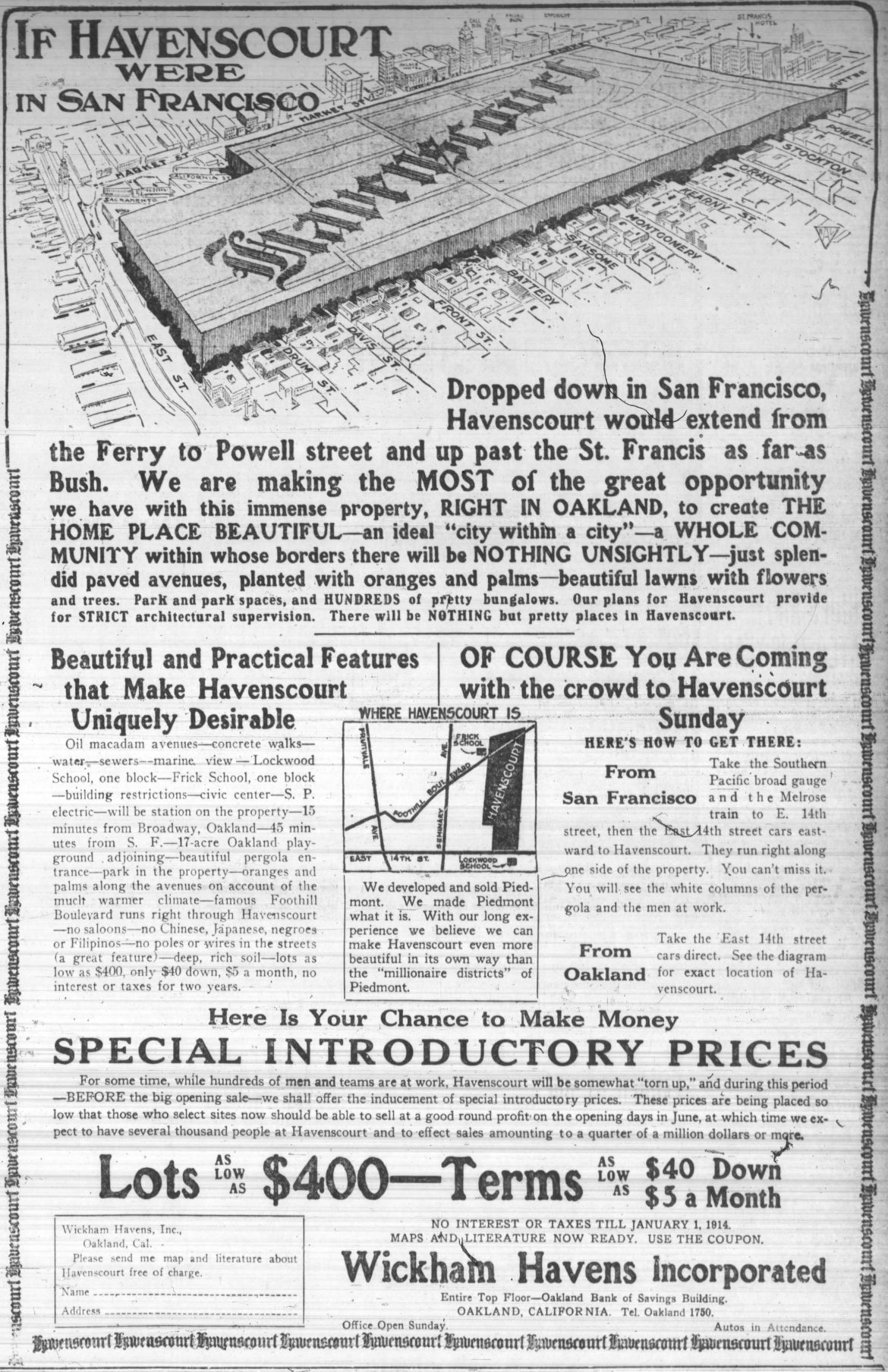

In 1910, Wickham Havens (Frank Havens’ son) marketed racial restrictions for East Piedmont Heights: “Here are the essential facts about this property… It is rigidly restricted and in a restricted section” (Oakland Tribune, 10/15/1910). A 1912 ad for Havenscourt, another Wickham Havens development in Oakland, says: “We developed and sold Piedmont. We made Piedmont what it is. With our long experience we believe we can make Havenscourt even more beautiful in its own way than the ‘millionaire districts’ of Piedmont.” The same advertisement promised “no saloons–no Chinese, Japanese, Negroes, or Filipinos–no poles or wires in the streets.”

The US Supreme Court outlawed racially-biased zoning in its 1917 Buchanan vs. Warley decision, but that did not stop whites from seeking other ways to exclude people of other races. Property owners started to include racial covenants in their deeds. These restrictions explicitly prohibited owners from selling or renting property to non-white buyers. And while the Supreme Court ruled in its 1948 Shelley vs. Kraemer decision that enforcement of these covenants by State courts was unconstitutional, many Piedmont deeds still include them. At present, homeowners can file paperwork to modify the language, but cannot remove it entirely. A new bill slated for introduction in the California legislature later this year seeks to change this situation

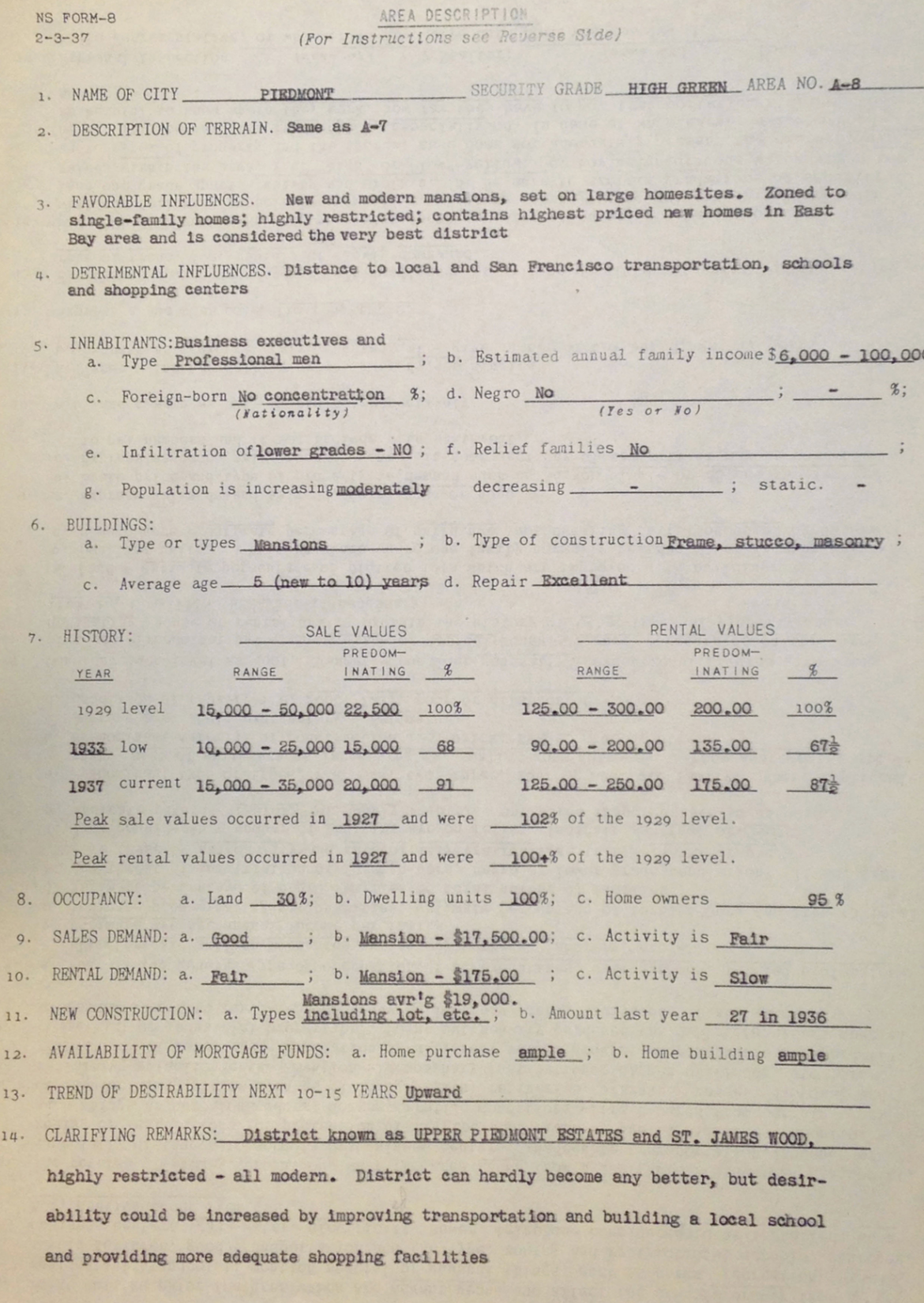

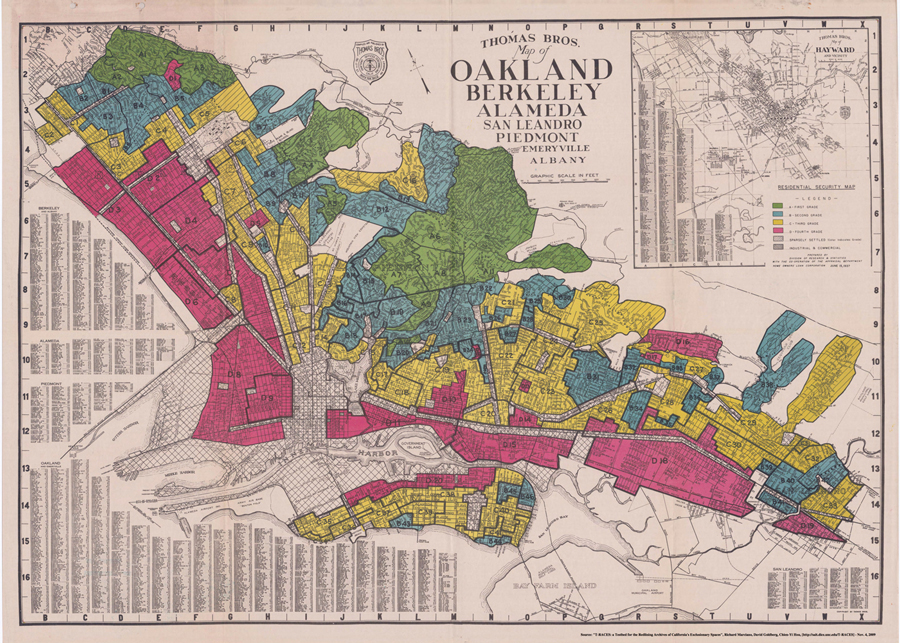

As Rothstein explains in great detail in “The Color of Law,” federal leadership has played a significant role in developing racist housing policy, too. In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration created the Home Owners Loan Corporation which, among other activities, drew up maps of cities graded on their so-called desirability. “First-grade” neighborhoods were labeled green, “second-grade” blue, “third grade” yellow, and the “least desirable” or “hazardous” areas were labeled red. Ratings depended on multiple factors, but arguably the most significant was race. “Hazardous” neighborhoods, outlined in red on the maps, were predominantly Black. Most of Piedmont was green-lined, which meant that homeowners in the city, unlike most residents of the redlined neighborhoods, could qualify for FHA loans and start to build equity in their homes. “So essentially, white families had access to mortgages, and they were allowed to buy single family houses that Blacks just couldn’t, because of the federal government’s policies, bank policies, and the private deed restrictions”, Cheng said.

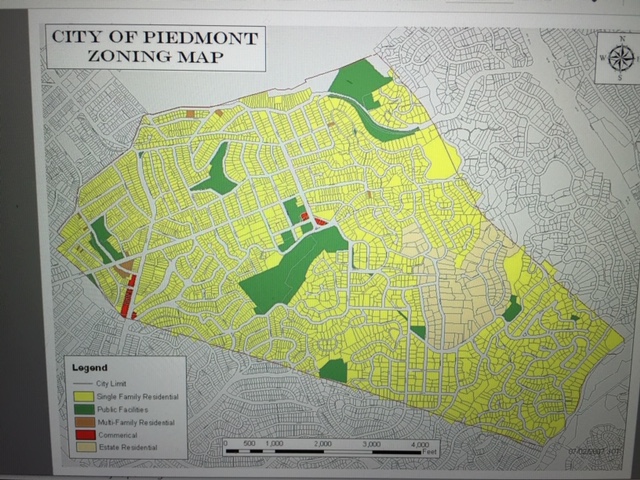

More recently according to Cheng, Piedmont’s almost exclusively single-family zoning has made it extremely difficult for any new housing to be built, since the city is already largely built out. This lack of developable land has contributed to massive increases in Piedmont home prices. These high prices, in turn, effectively exclude anyone who isn’t already wealthy from buying, or even renting, in Piedmont, further disadvantaging potential new residents, particularly Blacks and Latinos, who have been systemically denied – often through legal means –opportunities to build equity over time.

Rood agreed: “The segregated land use pattern created in Piedmont by the “whites only” tract maps and covenants in place throughout its development persists today, with 68% of Piedmont’s total land area, and over 99% of its residential land, reserved for the most expensive form of housing ever invented – the detached single-family home.”

Piedmont’s exclusivity has also been exacerbated historically by the subtle practice of “pocket sales” that may impede diversity. In these private arrangements, real estate agents, who are almost exclusively white and Asian in Piedmont, sell houses “off market” to their clients, who tend to belong to the same socioeconomic groups as the realtors and the sellers.

Cheng believes that most current Piedmont residents, like the real estate agents engaged in pocket sales, do not intentionally discriminate against people of color and/or those with less wealth and income. Nevertheless, they do unintentionally perpetuate historical inequities such as segregation and continue redlining into the present. “Most residents who move here are searching for good schools or other seeming advantages, which stem from racial inequities, that come with a community like Piedmont. I think most [Piedmont residents], if you ask them today, would say that they want to live in diverse neighborhoods. But there’s a kind of disconnect between that desire and their willingness to give up some conveniences or an attachment to what they know and feel comfortable with,” she said.

Rood noted that ”There’s a widespread sense that Piedmont is perfect just as it is, and that we can overcome the sordid legacy of discrimination simply by welcoming all new residents with the means to purchase a really expensive house and pay really high taxes. But as the Bay Area’s housing crisis continues, a more open mind about newcomers is not going to be enough to overcome the legacy of structural racism baked into Piedmont’s development pattern. Piedmont’s racial composition has diversified somewhat in recent decades, but economic segregation remains. The more diverse newcomers to Piedmont without these legacy advantages pay sky-high taxes and mortgages to secure a Piedmont education for their kids. Economic exclusion has a racial component.“

Looking to the Future

What would it take to make Piedmont more diverse? One of the main drivers is access to more affordable housing, according to PHS senior and Black Student Union President Harmonee Ross: “Piedmont [housing] prices need to be taken down so [Piedmont] can literally open up its doors to a diverse community.”

Many policy experts also believe that housing and zoning changes need to be made to increase diversity in places like Piedmont.

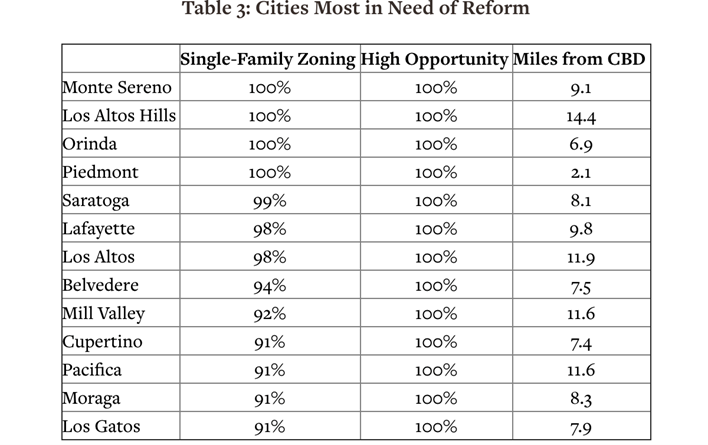

A recent study by the Othering and Belonging Institute (October 7, 2020) discusses the correlation between single family zoning and racial segregation. According to OBI, “Restrictive zoning is a powerful mechanism for hoarding resources, and that will not shift without actively re-shaping zoning regulations at the municipal level… The policy solution we advocate for is not to deprive single-family neighborhoods of resources, but to eliminate the barriers that prevent the rest of the Bay Area’s residents from accessing them.”

OBI’s zoning reform criteria include: 1) the percentage of residential land zoned for single-family housing; 2) an “opportunity designation” based on maps created by the Tax Credit Advisory Committee, which assesses sites for affordable housing developments; and 3) proximity to regional economic centers, or central business districts. This last criterion is especially important, because OBI does not advocate for locating additional housing in places like rural areas that, while they might also have exclusionary zoning policies, do not provide access to services that lower-income residents might need, such as grocery stores, libraries, health centers, and other community-based programs. Based on these criteria, OBI ranks Piedmont fourth of 101 Bay Area municipalities in terms of priority for additional affordable housing.

Sarah Karlinsky, the co-Chair with Cheng of PREC’s housing/zoning sub-committee, and a Senior Advisor at the San Francisco-Bay Area Urban Planning and Research Association, mentions three priorities for policy change in Piedmont:

“First, Piedmont can be an engaged, positive participant in the Regional Housing Needs Allocation process (RHNA). This process [which happens every 8 years] allocates growth targets across income levels to individual jurisdictions based on a variety of factors, including access to transit, good jobs, and good schools,” Karlinsky said. City leaders would argue that Piedmont has participated constructively in the RHNA process in the past two allocation periods (2007-15 and 2015-23), but it is also true that Piedmont has advocated to reduce its recent allocations and has not fully met the allocation goals, especially for low and very-low income housing.

“Second (and relatedly)”, Karlinsky continued, “Piedmont can find ways to increase its housing supply and the types of housing in the city. It would be great to find ways to allow for multi-family housing, including duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment complexes. Diversifying our housing will help diversify our residents.”

Cheng agreed: “When you look at the racial makeup of Piedmont, it’s apparent that the high cost of entry to Piedmont prevents it from achieving the level of diversity of many of our neighboring cities. So one thing we [PREC] are doing is trying to make other options available, [for example] by encouraging Accessory Dwelling Units, which provide much-needed rental housing for individuals and smaller households. Piedmont could also make it easier to build small apartment buildings or to convert a single-family house into a duplex or a triplex.”

Rood added that Piedmont, “nudged along by new state laws and regional planning mandates, has already eliminated many barriers to Accessory Dwelling Units, though they still often face backlash from neighbors more concerned about housing private automobiles on public streets than housing people. The next frontier will be overcoming the barriers to creating more of the “missing middle” forms of low-rise housing (duplexes, triplexes, bungalow courts, and small apartment buildings) that can be found in many older parts of Piedmont and often blend in perfectly with their single-family contexts. The beautiful Mediterranean seven-unit building at Linda and Kingston, the lovely shingled duplex at Moraga and Monticello, and the quaint hillside bungalow court on Moraga Avenue are all equally part of the legacy of Piedmont… allowing buildings like these to be created again is a necessary and important part of Piedmont’s future.”

Karlinsky’s third point is that “Piedmont [residents] could find ways to support affordable housing production, by voting for regional measures that create more funding for affordable housing and by also finding a way to incorporate affordable housing within Piedmont itself.” Alameda County Measure 1A from 2016 allocated $2.1 million to Piedmont for affordable housing, but none of these funds have been used to date.

In addition to housing-specific policy, Cheng also noted that housing is directly connected to education, another source of inequity. “In California, school districts are often tied to where you live,” she said. “If housing is segregated, [local public] schools are also often segregated, and that is true of our city as well. I would love to see us talk about having more diverse students in our schools, perhaps by expanding the inter-district transfer policy, and also potentially sharing funding across Piedmont and Oakland schools to start to break down some of Piedmont’s enclave status,” Cheng said.

Along these lines, PREC recently presented “Coloring Outside the (Red) Lines: The Impact of Racial Segregation on Piedmont Schools and Where We Take It From Here.” This discussion of how race and segregation have impacted Piedmont schools explored how to rebalance educational equity in the Piedmont community and beyond. The event was co-sponsored by the Piedmont Anti-Racism and Diversity Committee and the Piedmont Education Speaker Series.

How have all of these developments impacted the lives of people of color currently living and attending school in Piedmont? The third part of this series will address this vital question, and will include additional ideas for policy and cultural changes going forward.

Sources for this story include sidneydearing.com; “The Color of Law” (2017), by Richard Rothstein; “Single-Family Zoning in the Bay Area” (2020), by the Othering and Belonging Institute; Oakland Tribune; San Jose Mercury News; and KQED.

This Part II is excellent. A perfect follow-up to the first in the series. And, it wonderfully lays out our City’s need for affordable housing. I hope many of our residents are reading this. Thank you Marta Symkowick and Nick Levinson.

Is it time to rename the Havens Elementary school?