For a decade the office of Steve Humphries’ Piedmont home has been filling up with memorabilia — photos, newspaper clippings, miscellaneous stuff he acquired on eBay. Humphries, a former Piedmont High football coach, is a bit of a history buff, and he’s now assembling the team’s unofficial archive.

His uncle Craig Martin, who lives in San Mateo, shares Humphries’ enthusiasm for history. Martin spends much of his free time sifting through genealogy documents. Before coming to California, his ancestors moved between Scotland, Bali and Australia.

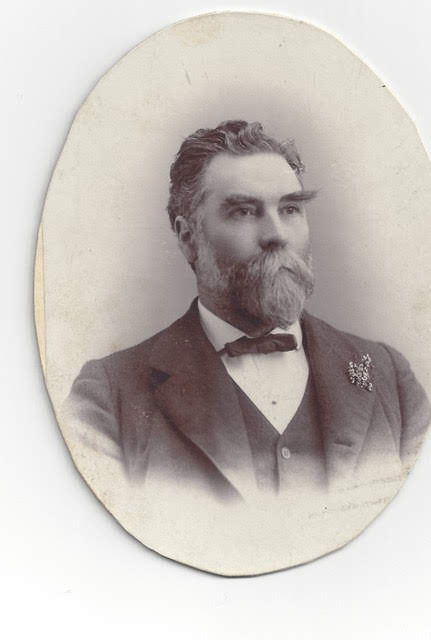

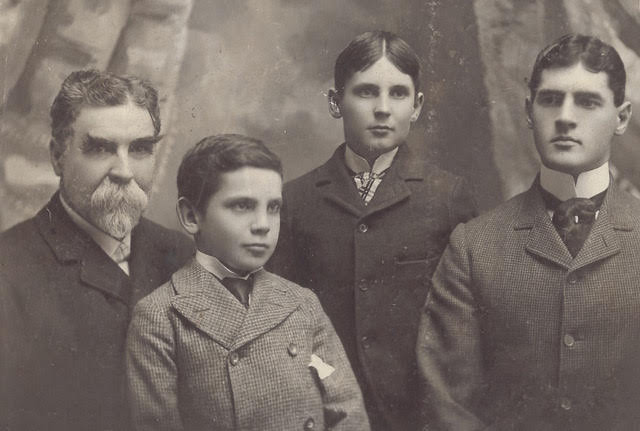

Humphries’ and Martin’s thing for local history may have to do with their family member having been an important Piedmont history-maker himself. Hugh Craig—their great-great grandfather and great grandfather respectively—was one of the city’s founding fathers (and second mayor). 113 years ago this month he successfully led the movement to fend off annexation by Oakland. Craig helped Piedmont become its own city.

The story of Piedmont’s declaration of independence has been widely covered, but the story of how the city developed the character we see in it today—the small town vibe, the love of tradition, the strong civic culture—is less well-known. So in addition to speaking to Humphries and Martin, The Exedra spoke to Piedmont historians and opened up the town’s archives to investigate what makes this town unique.

Hugh Craig envisions the Piedmont hills community as special, separate, and worth preserving

According to his daughter Evelyn Craig Pattiani in her book Queen of the Hills: The Story of Piedmont, Hugh Craig bought six acres of land between Vernal Avenue (now Highland Avenue) and Mountain Avenue in 1879. On land where springtime blooms swathed the hillsides in poppies and lupin, Craig built an English-style home. (In 1912, forced to subdivide his property due to a tax raise, he set the house on rollers and moved it 200 feet, to its current location on 55 Craig Avenue). Until 1907, what is known as Piedmont was an unincorporated area of Oakland.

Craig embodied what would become two key facets of the city’s character: a belief that this particular area of the Oakland Hills has a special beauty that will always attract wealthier families, and a willingness to invest in schools and parks and civic life to preserve its small town charm.

Born in Australia in 1842, Craig grew up in New Zealand. In 1870, after a number of cross-Pacific trips as a purser aboard the packet ship Nebraska, he settled in Oakland, and in 1875 he founded the New Zealand Insurance Company in San Francisco. He later served two terms as president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce. He married Inez Augusta Gilchrist, an Ohioan who had arrived in California with her family in 1867, and together they had six children.

When Craig and his wife settled in Piedmont in 1880 it was a sparsely populated patch of unincorporated forest and farmland. The indigenous Ohlone tribe had been mostly driven out by Spanish missionaries by the early 19th century, or killed by state-sponsored militias after California joined the union in 1850. By the 1880s, at least in the upper hills, Piedmont was already a “rich man’s town,” even though it wasn’t a town yet, according to Ann Swift, a Piedmont historian who served as city clerk for 25 years.

Compared to those residents — mining millionaires like Henry Butters and Isaac Requa, and James Gamble, the man who brought the telegraph to California — Craig hovered closer to earth. Although he was a successful businessman, at home he grew barley and oats for his horses. His commute to San Francisco, by street car and ferry, brought him closer to his neighbors, fostering an appreciation for their tranquil, family-centered lifestyle in the hills.

“The middle class lived near the street car lines,” said Gail Lombardi, an architectural historian for the Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey and member of the Piedmont Historical Society. “They would have had a sense of community.”

Craig quickly grew attached to his way of life in the Piedmont hills. He entered local politics in 1883, when he appeared before the county board of supervisors to stop construction of a rail line that would have cut through his property. He similarly bristled at disruptions to the broader community.

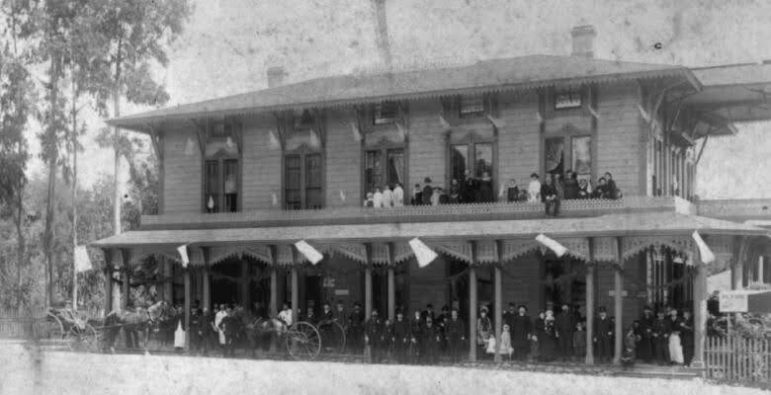

Ever since Oakland hotelier William Plitt had taken over management of the Piedmont Springs Hotel (located in what is now Piedmont Park), Craig felt the hotel cared less about attracting homebuyers from San Francisco with its supposedly curative, pink-water hot spring, and more on tempting scoundrels with the saloon. Craig petitioned the county to revoke the hotel’s liquor license, but was denied.

So, on November 17, 1892, when the hotel collapsed in a fire, Craig’s “surprise was tempered by elation over this providential removal of the blot on the center of the otherwise ideal home district,” writes Pattiani.

He also invested in the community. In 1897 Craig and other family-oriented residents built a new schoolhouse with $16,000 raised in bonds, up the hill from the Oakland side of the present-day intersection of Piedmont and Pleasant Valley Avenues. Like Piedmont, this land was unincorporated. Oakland, in the midst of an extended growth spurt, annexed the land and starting charging Piedmonters a hefty fee to use the school.

“Hugh Craig had six kids,” said Lombardi. “He would have seen an advantage to Piedmont developing its own schools.”

One of Craig’s wealthiest neighbors, Frank C. Havens, had made a small fortune as a broker in the early days of the San Francisco Stock Exchange. In 1895 he partnered with Francis Marion Smith—the “Borax King of Death Valley” who would use his millions to build the Key System, an early East Bay private mass transit system that was the forebear of today’s AC Transit. Together Havens and Smith formed a firm they called the Realty Syndicate; Smith was responsible for laying transportation infrastructure, and Havens for developing the land it ran through.

“His plan, which was brilliant, was to buy as much land as he could,” the historian Swift said of Havens.

Across the East Bay the Syndicate owned 13,000 acres. These holdings included the pasture land between Highland Avenue and Grand Avenue that had belonged to Walter Blair, Piedmont’s first white settler. Blair had arrived in 1852 and established a dairy farm and the Dracena Park quarry—which the Syndicate started developing in 1903. The company integrated and standardized the various transportation routes connecting Piedmont to Oakland, whose Key System was just starting to run.

In building homes and transportation infrastructure, the Syndicate was a big factor in stimulating the growth of Oakland. There would later be evidence that the Syndicate tried to have it both ways.

Independently, Havens bought the grounds of the fallen hotel, which he would develop into Piedmont Park. Combining these improvements, the Syndicate hoped to continue attracting wealthy homebuyers to the hillside community.

Meanwhile, Oakland was growing. According to Dennis Evanosky, author of East Bay Then & Now, Oakland underwent two major “bloomings.” The first started around 1869, when the first train of the newly completed intercontinental railroad disembarked at its West Oakland terminus. Between 1860 and 1880, Oakland’s population grew from 1,543 to 34,555.

The second came after the 1906 earthquake, when 150,000 refugees fled east to Oakland and surrounding areas from the rubble and embers of San Francisco. The Greater Oakland Movement, initiated in 1896 to grow the city’s tax base, mitigate the potential for municipal corruption, and amass political clout in Sacramento, now had to figure out how to accommodate some 60,000 new people who decided to settle in Oakland.

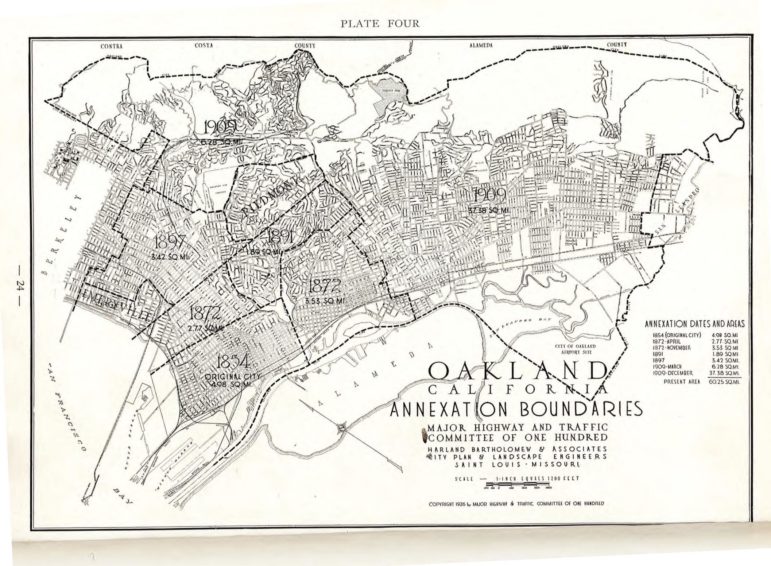

Oakland had annexed Temescal and Golden Gate in 1897, and was now looking east toward the hills. “A lot of these places—Berkeley and Alameda are the big examples—just laughed it off,” said Evanosky. But the smaller communities couldn’t mount so simple a defense.

With a lot of planning and even more luck, Craig and his supporters forced the issue of incorporation, and it broke their way

On December 1, 1906, the Oakland city council passed an ordinance to vote on the annexation of Piedmont, along with Fruitvale, Melrose, and Elmhurst. Voting day was originally scheduled for January 18t, 1907, but an error in the paperwork forced Oakland to temporarily retract its plans.

Craig, then chairman of the Piedmont Incorporation Club, saw this as his chance. In 1899 he had fought an earlier attempt by Oakland to absorb his community, and newspaper records suggest he spent practically all of December, 1906 arguing Piedmont’s case before the Oakland council. The delay in the annexation vote gave him, the attorney James Ballentine, and Varney Gaskill, Piedmont’s first mayor, time to schedule another vote.

On December 28, the men successfully petitioned to vote on Piedmont’s incorporation (“I can see no advantage in giving up our individuality in that way,” Craig explained to the council members), and on January 26t, 1907, with the sewer map defining the city boundaries, 79 men voted for and 38 voted against incorporation, securing the requisite two-thirds majority by two votes.

On January 26, 1907, 79 men voted for and 38 voted against incorporation, securing the requisite two-thirds majority by two votes

“It was lovely to remain Piedmont,” said Lombardi. “But a price came with it.” After years of relying on Oakland, the city now had to provide its own services.

On March 14, annexation was put to a public vote and came out 69 for, 43 against—but Piedmont’s fresh status as a city blocked the decision.

Looming behind the fidgeting public was a familiar force: the Realty Syndicate. According to an Oakland Tribune article from September 4, 1907, in January Craig cited the “beneficent influence” of the Syndicate as a key reason for incorporating. From the Syndicate’s perspective, annexation might have meant disrupting the system of land, transportation infrastructure, and water rights it had spent the prior decade buying and developing.

But the same article cites Craig, in September, outing the Syndicate as the hand behind a new movement in Piedmont. Pro-annexationists wanted to disincorporate and reverse a decision that they feared would raise their taxes. Craig, one of Piedmont’s five elected trustees, suspected the Syndicate had been alarmed by his suggestion that the new city raise tax rates on unimproved land.

The Oakland Tribune called Craig a liar: “Every person familiar with the facts knows this is not true,” it published September 4, but he may have had a point. Leading the disincorporation movement was Piedmonter Edward Engs, who is listed in the 1907 census as the Syndicate’s attorney.

On September 7, 92 men voted for disincorporation, and 63 voted against it. But this time they were a dozen votes short of the requisite two-thirds. Piedmont remained its own city, and by 1909 Oakland had annexed the remaining surroundings, locking in the borders as we know them today.

Humphries, Craig’s great-great grandson, suspects that beyond his family and city employees, Craig is just a name on a city street sign. “Most people who just moved here have no idea,” he said.

Many of the values that guided the fight for Piedmont’s independence continue to shape life in this hillside community. The limits on commercial business development keep the town quiet, uncongested and superficially unchanged, and ensure that a “blot” the likes of the hotel saloon can never resurface.

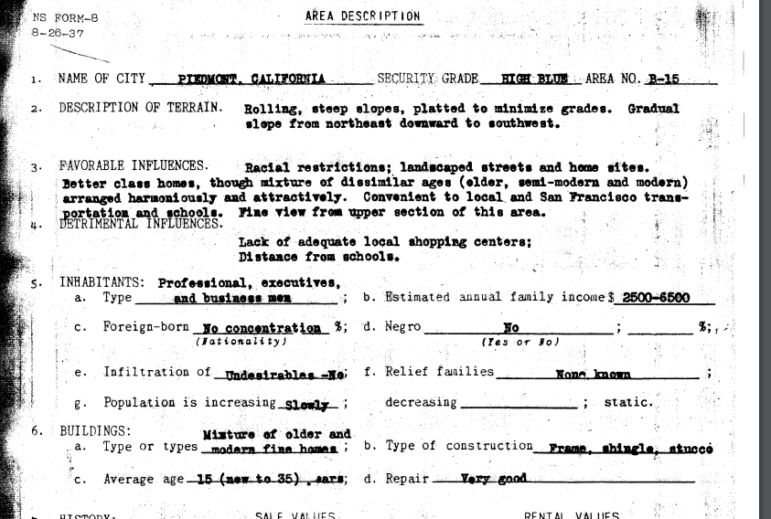

They also keep Piedmont racially homogenous. In the decades immediately following the city’s incorporation, Piedmont’s exclusiveness would be codified into something exclusionary: discriminatory practices known as redlining, designed to keep minorities out of town.

Piedmont, according to a 1937 document from the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation, was a “favorable” place to build and make loans because of characteristics such as “landscaped streets” and “Racial restrictions.” That year, Piedmont had no black residents. Although the practice was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the city was, and remains, predominantly white. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Piedmont is approximately 72 percent White, 17 percent Asian, almost 4 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 2 percent Black/African-American. By contrast, in the surrounding city of Oakland, White, Hispanic/ Latino and Black/African-American each make up about one quarter of the population. Asians are 16 percent.

But so persisted the town’s other foundational values. Education remains a priority–Piedmont schools consistently rank among the best in California, and family-centered traditions, such as 4th of July parades and Pinewood Derbys, still dot the civic calendar.

Much of what the city is today, both the intentional and the unexpected—flows from that time in 1906 when Craig, the Australian businessman for whom the Piedmont community became home, seized the moment and left his mark. “None of this would have happened if he didn’t have a passion for having a city,” said Humphries.

So more than a century later, what are today’s Piedmont citizens passionate about? And what kind of mark will they leave for the city’s future? It doesn’t seem like much of a stretch to imagine that Hugh Craig would have considered these questions the most urgently in need of good answers.

Great article, very interesting!

As a long time teacher and private tutor in Piedmont, I appreciate the depth of this article documenting Piedmont’s history. Good job!

Interesting article. It would be great during Black History month to address some more in-depth lengths of Piedmont’s redlining, KKK police chief in 1929 and Sidney Dearing who was our city’s first black resident who went through hell living here.

Wow yes I certainly would be interested in learning more about that!

https://www.sidneydearing.com/