Like many towns in California and across the country, Piedmont has a complicated and little-known history regarding race and the treatment of non-white people. This summer, Exedra intern and PHS grad Marta Symkowick ’20 researched the story of Piedmont’s first Black homeowner, Sidney Dearing, and how race has shaped Piedmont’s history over time.

We present Marta’s story in three parts, starting with Dearing’s ordeal. Part II addresses the history of housing discrimination in the city, and its effects on current race relations. Part III considers what lies ahead and how the city can work to address past wrongs.

Like every community, Piedmont is built on a shared story. The common experiences we remember and the experiences we live today shape our view of ourselves and the world. We like to think of ourselves as civic-minded, open-hearted, caretakers of our best traditions.

But what happens when important stories are left out or forgotten? That question came up in a recent conversation I had with Piedmont City Council member Timothy Rood. Rood told me how on his daily dog walks, he often passed by a home on Wildwood Avenue, decorated in purple wisteria and painted gray with white trim. It’s a lovely home occupied by a lovely family. Almost 100 years ago, it was just as lovely, and occupied by an equally lovely family. But their story is seldom told.

If you live in Piedmont, Councilman Rood told me, you should educate yourself about 67 Wildwood Avenue.

Rood said that he began by researching the subject himself. “I learned about this story from a post [of an old newspaper clipping] on an Oakland history Facebook group that I’ve been part of for a few years. I was really struck by it because I lived right down the street for many years. I saw that house every day.”

In 1924, the house was bought by Sidney Dearing, a wealthy man who became the first black homeowner in Piedmont. His story is worth remembering, although it is not taught in our school’s history classes. Soon after Dearing moved in, a mob of 500 white residents surrounded the house, demanding he move out of Piedmont because he was Black. After he refused, three bombs were planted on his property, at least one of which was active. Even in 1920’s segregated America, this was an outrageous act that made headlines in newspapers across California.

Rood’s research was sparked by a bit of consciousness-raising he experienced last spring while thinking about issues raised by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. He decided that this was an opportune moment for Piedmont to embrace the coming changes and move forward by reckoning with the painful aspects of its history, including those surrounding race and Sidney Dearing’s story.

Rood tapped into a cultural moment that other Piedmonters were feeling, too. In July, a group of anonymous high school students, also inspired by BLM and troubled by things they have seen and heard in our community, launched an Instagram account to expose racist behavior. They called it Reporting Racism Piedmont, and wrote that they started it with “the mission to illuminate the experiences of people of color in Piedmont Unified School District.”

Numerous other new Piedmont-based organizations have also started recently, including the Piedmont Racial Equity Campaign, the Youth Anti-Racism Project, and POPS, a group dedicated to bridging the educational divide between Piedmont and Oakland.

In early August, Piedmont took a huge step forward by voting in a formal repudiation of racism. The unanimous City Council resolution agreed to review city policies, procedures, ordinances, values, goals and missions “through an anti-racism lens.” Rood said an important aspect of the resolution is “examining and owning” the city’s history. Councilwoman Jen Cavenaugh stated that the resolution is just the beginning of the conversation. “I hope this is the first step of many,” she said.

Rood plans to continue to build on the resolution, potentially putting up a plaque or other memorial near the Dearing residence. “It’s important that we all understand what happened so we can appropriately respond to the effects of historic injustices around race that are still apparent in our community.”

Rood’s words inspired my curiosity to learn more about Piedmont history. When I was at Piedmont High School, I took AP US history. While we did learn about segregation in Oakland and Piedmont, we never learned about Sidney Dearing. When I began reading on my own, what I found shocked me.

The Creole Cafe – “Best Jazz Music and Entertaining upon the Coast. Southern cooking a specialty”

Grand Opening Notice, May 11, 1921

New Orleans-style jazz music twists down 7th Street in Oakland. Laughter fills the air in the self-proclaimed “leading cafe of the west,” as men and women step and twirl. Waiters bustle around with trays bursting with traditional Southern food. Almost 100 years later, I stand on the same 7th Street. My fingers trace all that remains of Sidney Dearing’s legacy, a single bronze plaque from the Oakland Walk of Fame stating, “The Music They Played on 7th Street — CREOLE CAFE.”

When Meghan Bennett, Piedmont resident and creator of a website devoted to Sidney Dearing, discovered how prominent a businessman he was, she was stunned. “[Dearing was so well known that] he had a plaque in West Oakland for his Creole Cafe. The city of Oakland recognizes him, but we [in Piedmont] don’t.”

Dearing was born on March 8, 1870 in Fredericksburg, Texas. He was a bartender there in the 1890s, and married his first wife, a Black woman named Lizzie Williams, with whom he had one son. After Dearing and Williams divorced, he moved to Oakland in 1907. He became the proprietor of the Creole Cafe in 1918. Dearing married Canadian Irène F. Davis in 1920, and they had two daughters.

“Sidney Dearing was definitely a hustler, which I believe to be his greatest strength, and what allowed him to persevere against great odds,” said Joseph Palmer, Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) President and genealogist. Palmer founded the historical society focusing on the Martinez cemetery potters’ graves, where Dearing was buried in 1953. Palmer has been working with Bennett to piece together Dearing’s story.

The Creole Cafe was one of the main jazz establishments that popped up in Oakland after the bohemian Barbary Coast jazz scene in San Francisco fell apart. The Cafe was where the Kid Ory Original Jazz Band, led by trombonist Kid Ory, made its debut in the Bay Area before becoming the first Black jazz band to make a recording. “It was crazy learning about the group that played at the Creole Cafe, and how they made the first record in L.A. a year later,” Bennett said.

The timing wasn’t ideal, however, since Prohibition had started in 1918. The Cafe was closed down by the federal government in 1921 (ironically, the year Prohibition was repealed) for possible alcohol consumption. “He was definitely a prominent businessman, and if it wasn’t for prohibition closing the Café down he could have done even better,” Bennett said.

Dearing’s wealth contributed to his ability to buy a house in Piedmont in January, 1924. One of the main reasons he was able to make the purchase was that he did not do it himself. Instead, his mother-in-law from his second marriage bought it for him, according to Palmer. “His mother-in-law was white,” Palmer said. “She married a Black man from Virginia who was Canadian.”

Since inter-racial marriage would only become legal in all U.S. states with the Supreme Court Case Loving v. Virginia in 1967, Dearing’s mother-in-law moved to Canada, where she raised her children. She later became widowed, which is one of the reasons that she most likely did not buy the house herself. “I suspect it was his [Dearing’s] own money that he gave his mother-in-law because from what I can tell, she was widowed at a very young age with young children at a time when it was [especially hard] to be a single mother,” Palmer said.

Dearing purchased the house at 67 Wildwood Avenue in January 1924, for what he said was $10,000. He therefore became the first Black homeowner to live in Piedmont. Yet Palmer said that it was no surprise that when the Piedmont community learned that Dearing was Black, they wanted him gone. The remarkable aspect is that after all the hostility he had to endure, Dearing continued to fight. “The courage that he had to have had [to continue] against all odds is remarkable,” Palmer said.

“Piedmont has race war peril on its hands”

Whittier (CA) News, June 9, 1924

On May 6, 1924, at 8 pm, 500 angry white Piedmonters surrounded 67 Wildwood Avenue. The mob demanded that Dearing “name his price” to buy the house back from him. The police were called to help calm the increasingly violent protestors, but it was only after Dearing agreed to meet the next Tuesday to arrange for the sale of his property that the crowd finally dispersed.

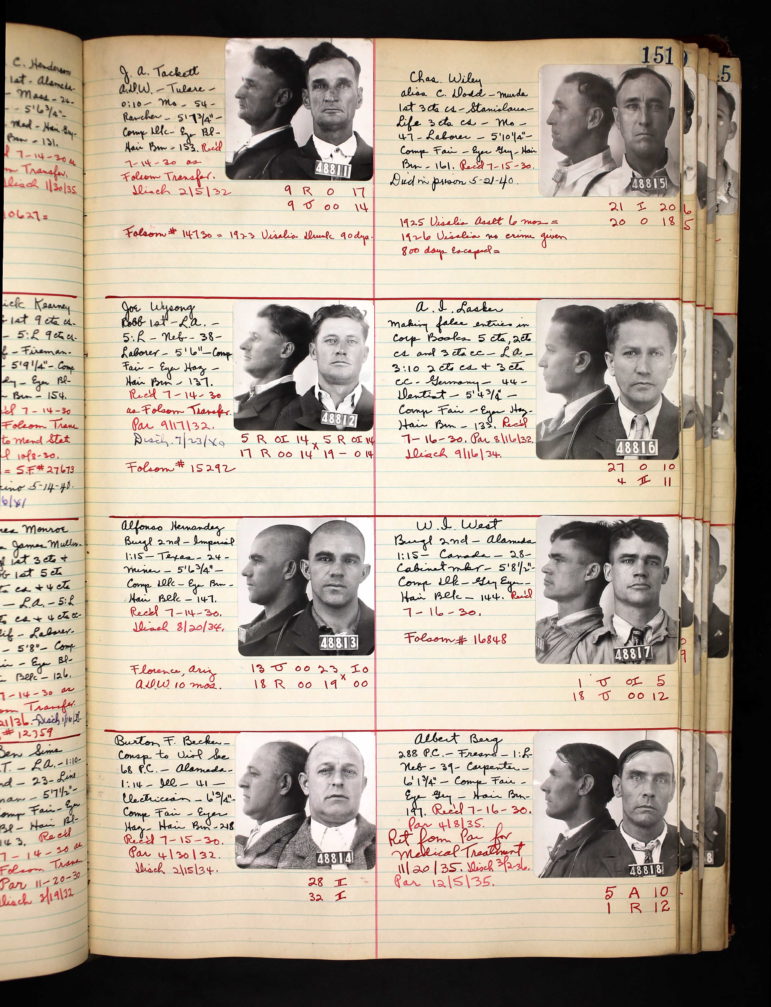

Unfortunately, as we have seen happen all too often recently and throughout US history, the police were a large part of the problem, not the solution. The same year Dearing was threatened because he would not leave his home, 3,000 members of the Knights of the Klu Klux Klan marched on the 4th of July in Richmond, CA. Oakland Klan No. 9 Chapter, led by Piedmont Chief of Police Burton Becker, entered a drill team for the parade.

By 1924, the KKK had become so widespread in the Bay Area that the residents of Piedmont knew that Becker was a member. He had previously publicly declared his affiliation and had appointed Klansmen to positions in the police department. (Becker and other Klansmen were kicked out of the KKK for attempting to commercialize the name in Nevada. He was then elected Sheriff of Alameda County in 1926, where he became involved in a major bootlegging scheme. Becker was investigated by then-Alameda County District Attorney Earl Warren in 1930, then convicted and imprisoned at San Quentin Prison, where he died.)

Becker unsurprisingly refused to provide Dearing with adequate police protection, and the sheriff of Alameda County, Frank Barnet, had to step in.

Protests started after Dearing refused to sell the house to the West Piedmont Improvement Club for $8,000, 20% less than what he paid. When interviewed, Dearing said that he had been requested to move simply because Piedmont property owners did not want to have a colored resident in their community.

The week following the protest, Dearing moved the location of another arranged meeting to his house, citing his safety. He hired four armed guards, installed three locks, and moved his family out of the house to his mother-in-law’s residence in Oakland. Dearing countered that he would not sell under “peaceful conditions for less than $15,000, and that under the present harsh conditions for nothing less than $25,000. [$10,000 of the price is for] the surrender of constitutional rights,” he said.

But the threats did not end. On June 1, a bomb made of stolen dynamite was discovered planted in the shrubbery between Dearing’s house and his next-door neighbor’s, who had been leading the fight against Dearing. He was now spending only two hours a day at his house, but still refused to abandon his property. “The fact that he doesn’t succumb to the pressure, demanding that if you’re going to buy me out, you’re going to pay me this much [is incredible],” Palmer said.

Later, two more bombs were found planted around the Dearing residence. He came home to discover the third bomb with an actively lit fuse in his backyard. He quickly stamped it out and ran around the corner to take cover. When he came back, the bomb was gone, taken away by those who had planted it. Later, after being notified, Piedmont Detective Sergeant Frank Heere said, “I believe that Dearing’s story is true. I have every reason to believe a third bomb was thrown at Dearing’s home, as he told me. However, I am not interested in it.” It was reported that at this point, the Piedmont Police simply refused to investigate the “secret organization” (assumed to be the KKK) that was threatening Dearing.

“The matter of condemning the Dearing property and building this street will be for the improvement of the city as well as to make the negro move from Piedmont.”

Piedmont Mayor Oliver Ellsworth, Oakland Tribune, June 12, 1924

On June 5, 1924, the members of the Piedmont City Council slipped into the council room. A pause, and then the debate began. The problem: Sidney Dearing. Holding firm against a violent mob and three bombing attempts, it was clear that Dearing would not be scared off his property by mere Piedmont citizens. The vote was cast. The City Council would intervene.

The next day, the Council offered to pay $8,000 for the property. When Dearing refused, the Council moved to condemn the property under eminent domain, which gives the government the right to seize property necessary for public works. In this case, the Council claimed they needed the Dearing property to build a street between Wildwood and Fairview Avenues. They were so committed to removing Dearing that they even filed a suit condemning a portion of a white resident’s property behind Dearing in order to construct the street.

Even with all levels of white power in Piedmont arrayed against him, Dearing still continued to fight. When the government condemned his property and sued, Dearing filed a counter-suit, hiring John D. Drake, a lawyer and President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAAC) Northern Chapter, to represent him.

Dearing and Drake attested that the City could not file for eminent domain if they had no actual intention of constructing the proposed road. They claimed that race alone was not grounds for his removal. In an article in the Oakland Tribune, Drake said the following: “In reply thereto it might be well to state that this is a question not only affecting Mr. Dearing, but affecting the rights of every American citizen. If the city of Piedmont can hide behind the flimsy subterfuge of a public necessity that does not exist, and set at naught the constitutional rights of an American citizen and take away his property simply on the ground of his color, so may the constitutional rights of any other American citizen be set at naught when he shall insure the displeasure of his more powerful associates, and we may at once say farewell to the constitutional government and to the principle on which we have counted for our safety. Such action would seem to indicate that we are governed by prejudice and passion and holds up your city to ridicule and gives the lie to our much boasted claim of democracy. So it is needless for me to state that Mr. Dearing authorizes me to say that he refuses to consider such an offer.”

Unfortunately for posterity, the story trails off after Drake’s rousing defense. We do know that Dearing agreed to sell his Piedmont house in February, 1925. The relevant sources do not mention how he came to make the decision, how much the house sold for, and what happened at the time to the city’s condemnation suit. (We do know now that the street was never built.) Dearing lived in Oakland for another 28 years until his death at age 83 in 1953.

How far have we advanced since Dearing’s time? Who was the next Black family to try to move into Piedmont? How has Piedmont addressed these racial issues in terms of housing, policing, schools, and community acceptance? Part II of this series will address these topics.

Please visit www.sidneydearing.com for additional resources. Other sources for this story include the Oakland Tribune, San Francisco Examiner, Sacramento Bee, Whittier (CA) News, Ogden (UT) Standard-Examiner, and “White Nativism and Urban Politics: The 1920’s KKK in Oakland, CA”, by Chris Rhomberg, University of Illinois Press, Winter 1998.

Courage, wealth, savvy, and excellent legal representation we’re all critical for Mr. Deering to press on. Only God knows how many Black people have been unjustly stripped of their home or land. Racism-white superiority is detrimental to a vibrant wholesome strong city, state, and country.

I have been so moved by what Mr. Dearing and his family had to go through, their persistence for racial equity, change and their bravery!! I look forward to learning more and am very appreciative of your excellent journalism, Marta!!

Educational article. It might be worth noting that Deering was from the West Indies and of African and South Asian heritage.

Thank you for this excellent article. It’s shameful that even long-time Piedmont residents did not know this history, and it’s so important to bring it to the fore.

I live next door to that house. We need a historical marker on it! We need a City Council resolution acknowledging the part played by the city, its police chief and its citizens in the harassment of the Dearings.

And let’s be real, racism is still happening today in Piedmont.

How horrible, cruel and unjust…and how interesting that we are (most of us) just now learning about this. White privilege still echoes in Piedmont all around us. This very well-written article may help us readers to recognize our own innate prejudices and get them behind us. Thank you, Marta. I, too, look forward to reading the next installments.

Excellent article and historical accounting. Heartbreaking to read. But it is so important for us to know our past to make the needed changes in our City culture.

I hope all residents take the time to read this and the next 2 installments. And, I am so proud that this was written by a PHS person. Thank you Marta!

Nicely done, a very important story to tell.

Thank you Marta!

Sad story and a terrible past. Thank you for the article.

Admitting to and learning from bad actions in the past is the only way to improve.

Thank you for researching and writing about this important history.

Good research! Well done. Looking forward to reading the next installment!

Great article.