Amid California’s mounting literacy crisis, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond named two statewide literacy directors, Nancy Brynelson and Bonnie Garcia, Thursday as part of a push to get more California third-graders reading by 2026.

“We know that when students learn to read, they can learn to read anything,” said Thurmond during a press conference, “but yet, this milestone has evaded so many in our country for so long, and California is focused on how we’re going to get there.”

Brynelson, one of the primary writers of the English Language Arts framework, and Garcia, a dyslexia specialist with a background in structured literacy, will be the new co-directors for Statewide Literacy at the California Department of Education, helping guide school districts on the best practices of evidenced-based methods grounded in the science of reading, officials say, but not bound by it.

“We are not interested in policing pedagogy or orthodoxy,” said Deputy Superintendent of Public Instruction Steve Zimmer, a former teacher. “We are interested in accelerating and expanding what has been proven to work on the ground. There’s an abundance of evidence that shows the critical importance of building foundational skills in the early years.”

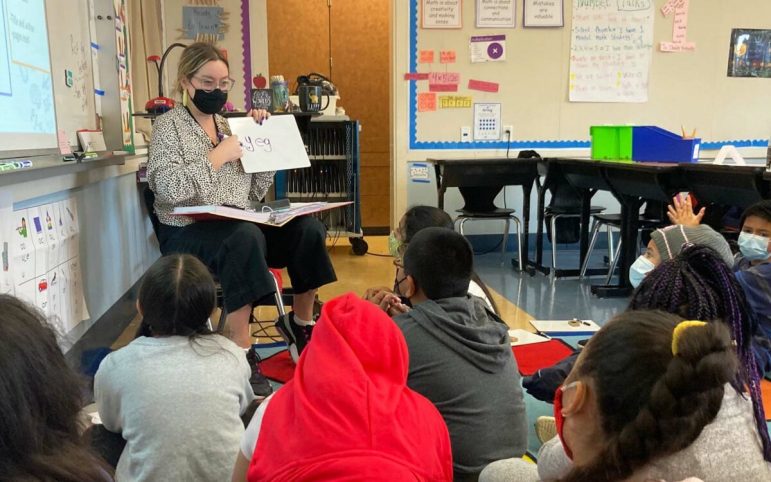

After a longstanding national debate over reading philosophy, some literacy advocates are pleased that the state is highlighting structured literacy, an approach backed by decades of exhaustive scientific research that has recently gained traction nationally.

Structured literacy stresses explicit lessons on reading fundamentals such as phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

“The most important thing is that they are making early literacy a top priority,” said Todd Collins, a Palo Alto school board member and an organizer of the California Reading Coalition, a literacy advocacy group. “It’s good they are introducing the literacy directors, and it’s nice they are getting some spotlight. If there is legislation, people like this at the CDE can be really helpful in implementing things. In other states, they play a very important role.”

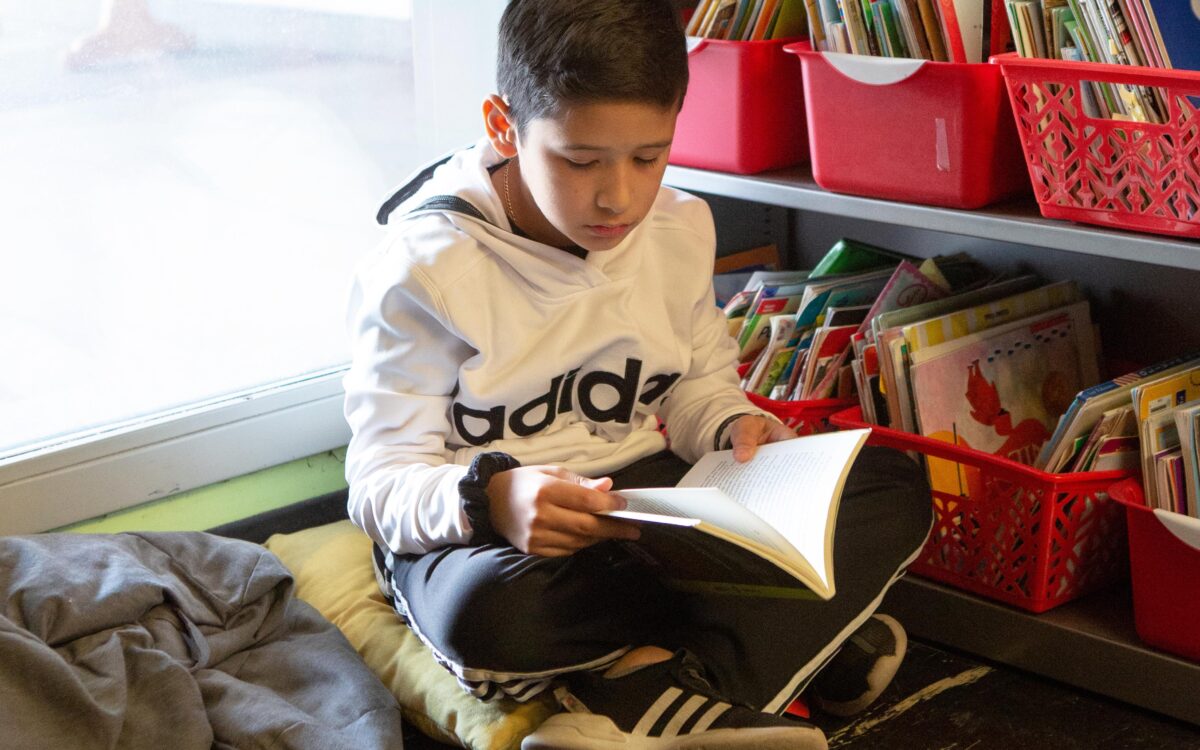

These steps are being taken in the wake of the state’s plummeting test scores and growing awareness of literacy as a civil right too many children are denied. Last year, almost 60% of California’s third-graders, the students most deeply impacted by distance learning and other Covid disruptions, could not read at grade level. Although it should be noted that reading scores have long been languishing, in the wake of the pandemic, roughly 70% of low-income students fell short of grade level.

“The reality is, yes, we do have a lot of catch-up work to do,” said Thurmond. “When you look at reading overall in California, you will see less than half of students reading on grade level. You will also see that when you look specifically at subgroups, African-American students, English learners, students with disabilities, those numbers drop.”

Since reading is a cornerstone skill that lays a foundation for all future learning, including math and science, many regard plunging test scores as cause for alarm.

“It is a great tragedy, and I firmly believe a preventable one,” said Sanam Jorjani, founding co-director of the Oakland Literacy Coalition. “I believe our kids are capable learners and that reading is in reach for all California’s children. They are not broken, and they are not at fault, but they do need support.”

Literacy advocates have long made the connection between rising illiteracy rates and lives on the margins of an information economy where the ability to quickly acquire knowledge is a key survival skill.

“We know, sadly, that when students don’t learn to read by third grade, they’re at greater risk for not graduating,” said Thurmond. “They’re at greater risk for dropping out of school, and they’re at greater risk for ending up in the criminal justice system.”

It should be noted that the new statewide co-directors will be helping school districts build their own literacy plans, and not mandating that they follow any one approach. They plan to offer tools and techniques to meet local demands, officials say, ranging from the needs of English learners to dyslexic students.

“It’s a great first step, but the rubber hits the road with implementation,” said Jessica Reid Sliwerski, a former teacher and CEO of Ignite Reading, a Zoom-based reading tutorial.

“You can have a well-meaning policy, but there have to be guardrails around how that policy turns into meaningful action.”

Some literacy advocates worry that unless the state imposes requirements on districts regarding how to teach reading, as Mississippi and Tennessee have done, little may change. Each of California’s 1,000 districts is allowed to decide how and what to teach.

“We’re talking directly about the science of reading,” said Thurmond. “In California, there’s no state mandate for what districts use. That will require new legislation. Until that should happen, we’ll be working with districts to make sure they get access to all aspects of literacy, including structured literacy.”

Many districts espouse balanced literacy, an approach popularized by Lucy Calkins in her influential “Units of Study” curriculum that often downplays phonics in favor of trying to instill a love of reading, sometimes encouraging children to guess at words using picture clues rather than sound them out.

“Unfortunately for students across California, balanced literacy will likely be alive and well for years to come,” said Megan Bacigalupi, co-founder of CA Parent Power, a statewide parent advocacy organization. “Without accountability and mandates, what is going to compel districts to change, when for years we’ve known how kids learn to read, we have seen millions of kids struggle, and few changes have been made.”

Thurmond also announced $1 million in grants to expand literacy programs at Freedom Schools, an Afrocentric program of the Children’s Defense Fund. He also launched a series of webinars geared to highlight best practices to boost literacy.

“We provide these culturally responsive reading opportunities,” said Kristal Moore Clemons, national director of the Freedom Schools. “Children can’t be what they can’t see.”

The co-directors will also lead webinars, help guide the state’s $250 million reading coach and specialist training program and partner with the Commission on Teacher Credentialing to help implement recently adopted literacy standards in teacher preparation.