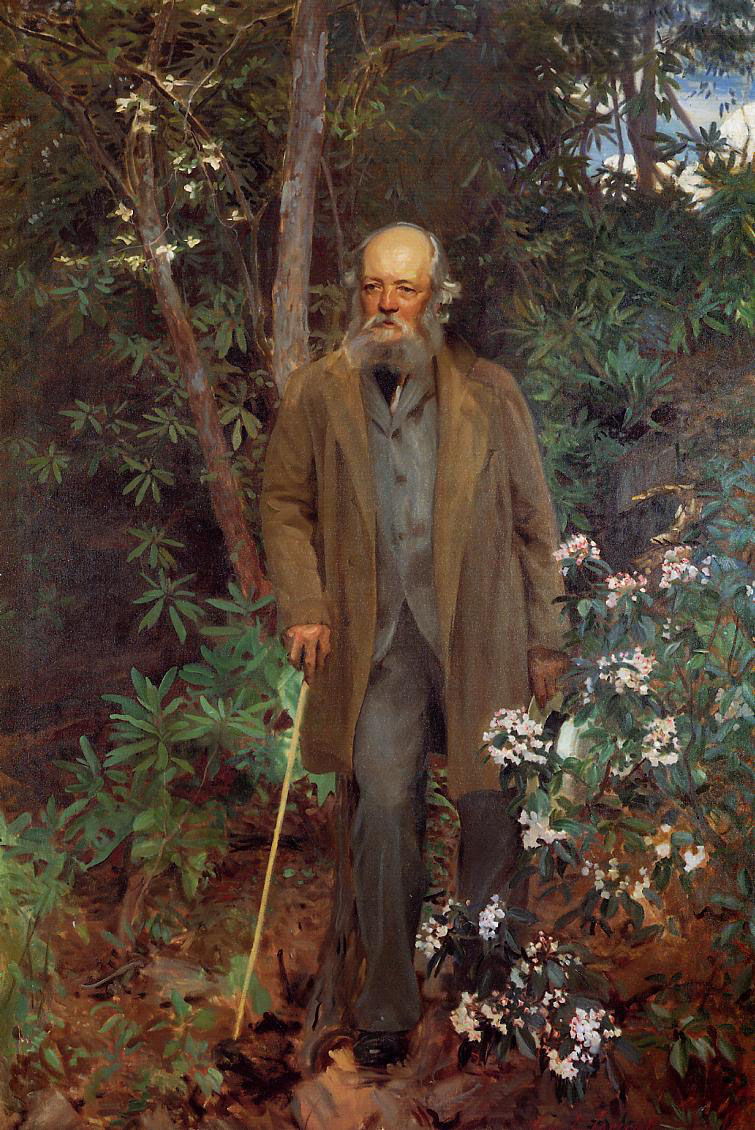

Oakland and neighboring cities are fortunate recipients of the legacy of the landscape architect, author, journalist, city planner, public official, and creative genius who transformed the American landscape. Already celebrated as the designer of Central Park (1857), the Connecticut-based designer Frederick Law Olmsted found himself in the wilds of California just as Oakland was booming and in need of a grand vision for a cemetery.

Oakland was incorporated as a town in 1852. The core of the town was on both sides of Broadway, just up from the waterfront. The first burials were out of town, 16 blocks away on Oak Street between 7th and 11th Streets, near today’s Lake Merritt BART station. In those days, burial grounds were dreary and used all available space. Bodies were buried very close to each other, sometimes on top of each other. There was no room for plantings and no temptation to linger.

By 1857, that first cemetery was filled. Oakland officials moved the cemetery an additional 10 blocks away to Webster and 17th Streets, near today’s Snow Park. At that time, it was well out of town. Bodies were dug up and reinterred in the new Oakland Cemetery. Record keeping was poor and not all of the bodies were reinterred. When Mountain View Cemetery was established, these bodies were moved again.

Oakland continued to grow, and by 1863 this second cemetery was nearly full. It was no longer out of town. It was blocking civic expansion and posing a health hazard. Dr. Samuel Merritt formed a board of trustees of twelve Oakland leaders for yet a new cemetery. Trustee Isaac Brayton owned 200 acres of land two miles out of town – so far from downtown Oakland that development would never encroach on this land. In February of 1864, the Mountain View Cemetery trustees bought the land for $13,000 and began looking for someone to develop it as an attractive rural cemetery. Fortunately, Frederick Law Olmsted was in California. He was already famous for designing Central Park in New York City and had travelled to Mariposa in 1863 to manage a gold mining operation.

In 1864, Olmsted met with the Mountain View Cemetery trustees and said he’d take a look at the land. The bare hills intrigued him, and he saw the land as a palette for some of his landscaping ideas.

In September of 1864, Olmsted signed an agreement with the Mountain View Cemetery trustees. It was his first independent commission and the only cemetery Olmsted designed.

Olmsted’s design of Mountain View Cemetery followed the principles of the Rural Cemetery Movement, which began in the 1830s in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Cemeteries were no longer barren and desolate. They were designed to be sanctuaries — a place of solitude, quiet, and beauty. Cemeteries were planted with trees, shrubs, and flowers, and families could leave the city, picnic on the cemetery grounds, and take long walks among the trees in peaceful settings.

Frederick Law Olmsted took one look at the surveyor’s topographical map of the Mountain View Cemetery site and saw the best design for the cemetery. He traced his finger in a straight line from the entrance up the center of the land toward the top of the hill.

The bare hills intrigued Olmsted who saw them as a palette for his landscaping ideas. He divided this central avenue into several parts with circles he called “rond points” where pathways radiated. In the flatter portion of land, the pathways were straight and defined diamond-shaped plots. In the hillier portions, the pathways followed the contours of the land and formed the boundaries for cemetery plots.

Olmsted’s main avenue in Mountain View Cemetery

One of the rond points as a fountain flanked by cypress trees

Winding paths as designed by Olmsted

Olmsted’s plan included trees and shrubbery, like a park. He recommended that the trustees line the central avenue with cypress trees, and that they plant hedges around the plots. He also urged the trustees to plant large trees of simple form and compatibility and listed five specific trees for the cemetery. To the native California live oak and Monterey cypress, he added Italian cypress, Lebanese cedar, and Italian stone pine. The Italian cypress is a favored cemetery tree. Simple and dignified in form, it points toward heaven and is symbolic of immortality. The dense, Italian stone pine complement the heaven-pointing Italian cypress trees, and the broad, sheltering branches of the live oak canopies sheltered the deceased. Today, the “Trees of Mountain View Cemetery” booklet highlights 28 noteworthy trees.

The cemetery trustees accepted Olmsted’s plan, and in September of 1864, Olmsted signed an agreement with the Mountain View Cemetery trustees.

Mountain View was his first independent landscaping commission and the ONLY cemetery that Olmsted designed.

In a letter written in San Francisco, Olmsted stated, “I am going to lay out a burying ground near here & it is a great comfort for me to have that object.” In addition to having the palette of the cemetery land for his design, Olmsted was planning to build a home for his family, and the commission was welcome.

Fun facts and roads not taken

While Olmsted was in Oakland, Mountain View Cemetery trustee Rev. Isaac Brayton took him out to Berkeley and asked him to design a plan for Brayton’s new College of California, the future University of California. Only Piedmont Avenue (formerly “Piedmont Way”) in Berkeley survives from this plan.

Olmsted also recommended that Oakland preserve its green areas while land was cheap. He suggested a belt of parks along the crest of the Oakland hills and down through the natural canyons. He urged that these park strips be 100’ wide on each side of the canyons to the bay. His ideas were not followed.

As he had in Central Park, Olmsted worked with surveyor Edward Miller on the cemetery design. It was on Miller’s map that Olmsted traced his finger and laid out his design. Olmsted did not remain in California to see the completion of his Mountain View Cemetery design. He left surveyor Miller to supervise the construction of his design, and Olmsted returned to New York in 1865 to work again with Calvert Vaux, his partner in designing Central Park.

The Rural Cemetery Movement

Mountain View Cemetery is an excellent example of the Rural Cemetery Movement which shifted the perception of cemeteries from dour graveyards to serene outdoor spaces that honored the dead and embraced the living. Olmsted believed that the perfect antidote for the stress of urban life was a nice stroll through a pastoral park. Before the widespread development of public parks, rural cemeteries offered a place to enjoy the out of doors. They were usually within five miles of the city and easily accessible to city dwellers. Landscaped as a park-like setting with pathways that followed the natural contours of the land, these cemeteries retained natural features like ponds, rock outcroppings and mature trees. Families could leave the city, picnic on the cemetery grounds and take long walks among trees and serene settings.

Olmsted design principles

Mountain View Cemetery is not a public park like Olmsted’s other designs, but it does exhibit some of his design principles. Olmsted studied the cemetery site and utilized its topography of numerous hillsides to design winding pathways to offer spectacular views. Olmsted scholars call his use of natural topography his “Genius of Place” design principle.

Olmsted’s “Uniform Composition” principle stated that no one garden feature should stand out. In a cemetery of many grand monuments, this is difficult to see, but Olmsted’s recommended large trees of simple form provide that uniformity. Olmsted’s principle of “Sustainable Design” stated that a design should allow for long-term maintenance and conserve the natural features of the site.

Today, Mountain View Cemetery continues to exhibit Olmsted’s original 1864 design in its Main Avenue straight up the middle of the cemetery. His “rond points” are four fountains today where pathways radiate. Cypress trees now surround each fountain. Olmsted’s original diamond-shaped pathways in the lower, flatter portion were modified by the construction of the 1929 mausoleum, but his pathways in the hillier portions continue to follow the contours of the land and offer spectacular views of San Francisco Bay. Olmsted also included three ponds in his design, still present in the southeast portion of the cemetery.

Contrary to Olmsted’s original intentions that the cemetery be reserved as a place of reverence for the dead — and not for recreational purposes — walkers and picnickers have enjoyed the cemetery’s winding paths, views, beauty and quietude for decades, just as they enjoyed Olmsted’s city parks.

The pandemic and complications with the city of Oakland have rendered the grounds off-limits for the last 14 months, and the public is anxious to make use of the grounds once more.

The coming year marks the Bicentennial of Olmsted’s birth, with celebrations planned in parks and green spaces across the country. Visit Celebrating Olmsted: Parks for all people to learn more.