Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, warned last week that families may need to change their Thanksgiving plans to keep everyone safe from the coronavirus. The head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Robert Redfield, expressed similar concerns in a call with governors.

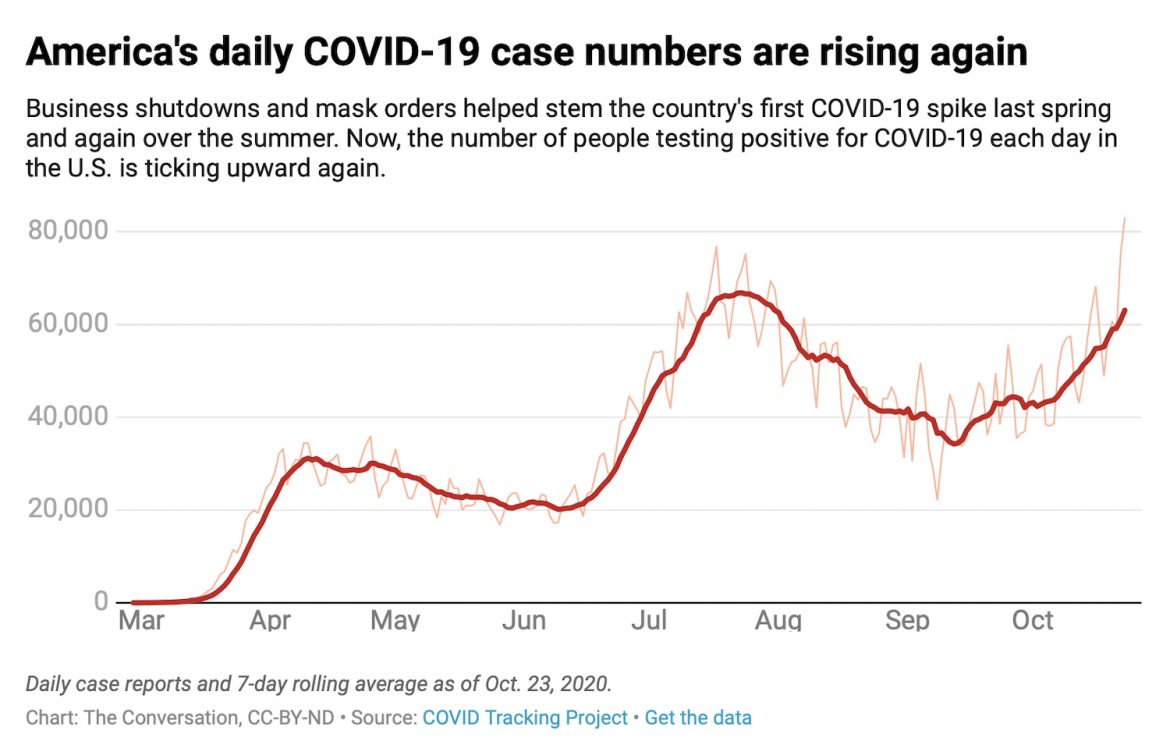

There has been an alarming increase in COVID-19 cases in most states in recent weeks, and we have seen cases rise in college towns in particular. Colder weather means more activities are moving indoors, where the virus can circulate. And people who have been socially isolated for months feel desperate for connection.

As the holidays approach, one important question is what impact sending college students home for Thanksgiving will have on their home communities.

The Public Health Response Team at Texas A&M University, which the three of us serve on, has been documenting COVID-19 trends in Texas for the past six months and forecasting disease spread and the impacts on hospitals. With new cases ticking upward, we have been concerned about what the holidays will bring.

Dual hot spots

In Texas, the most densely populated counties have a higher proportion of documented SARS-CoV-2 infections, and they contain a majority of the state’s colleges and universities. The intersection of these features creates challenges for controlling COVID-19.

Many of these counties were already COVID-19 hot spots before students returned for the fall semester. In more crowded communities, the chance of random exposure to someone with COVID-19 is a lot less random and a lot more certain.

Reopening the campuses brought in an age demographic known to harbor the virus but often with only mild symptoms or no symptoms at all. This facilitated covert spread of the virus. Nationwide, many universities reported a surge in cases shortly after students returned in the fall, and some had to stop in-person classes and shift back to online learning when those cases got out of control.

Soon, these students will be returning to their families around the country for the holidays, and bringing with them the possibility of a souvenir no one wants — COVID-19.

Cause for concern

It’s not just campus activities that raise concerns. It’s also what students do when they aren’t in class, including going to bars and attending off-campus parties.

In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott recently relaxed the minimal restrictions for bars, allowing them to open at 50% capacity. This likely means that bars — chafing from being treated differently from other places where people gather in groups — will be rarin’ to go. With young adults, the likelihood of failing to remain vigilant about social distancing, mask-wearing and other precautions is already a concern. Such risky behaviors would compound the risk factors, facilitating extra opportunities for the virus to spread.

We hypothesize that factors such as college drinking, peer and social pressure to act as if everything is normal, as well as seasonal changes that make outdoor eating and drinking less feasible, will increase the likelihood of exposure to the coronavirus and subsequent infection.

As these young adults return home, some will probably have signs of mild illness. Some may have no discernible symptoms but will still be infectious. They could introduce the virus to communities that have had few infections so far and to the friends and family, including vulnerable parents and grandparents, they have been eager to reconnect with.

While we have been studying the dynamics of COVID-19’s spread in Texas specifically, many other states with large college populations face the same combination of factors, with potentially infectious young adults heading home. It’s important to understand the risks. Nationwide, more than 215,000 people who got COVID-19 had died by mid-October.

So what can be done now?

First, university and town officials can prepare for these upcoming risks. Efforts to contain and mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 on campuses and in surrounding communities are as important as ever.

Some campuses are planning to end the semester at Thanksgiving break or shift to online classes for the final weeks to avoid additional travel that could spread the virus. Others have implemented rigorous testing and contact tracing programs to help stop the spread.

Second, everyone needs to take COVID-19 public health preventive practices seriously. That means avoiding large gatherings — and even smaller ones when new people are involved — wearing face masks, and following the recommended physical distancing guidelines. When going to bars or restaurants, be aware of how well the customers and the businesses take precautions.

Third, everyone should realize the upcoming holiday season will be different from those in years past. Students whose semester won’t end until December should consider avoiding travel until the end of the year — or, if they are traveling earlier, to do it safely. One strategy is to get tested before heading home and again before returning. If you aren’t able to visit your grandparents and other family members in person, you can find remote ways to still connect, such as phone calls or video chats.

We wish everyone a good and safe holiday season — keeping yourself and others safe will mean knowing what the risks are and proactively taking steps to ensure many more happy family holidays to come.

* Walter Thomas Casey II is associate professor of political science at Texas A&M University-Texarkana; Marcia G. Ory is a regents and Distinguished Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at Texas A&M University; Rebecca S.B. Fischer is assistant professor of epidemiology at Texas A&M University. The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This story originally appeared in The Conversation.