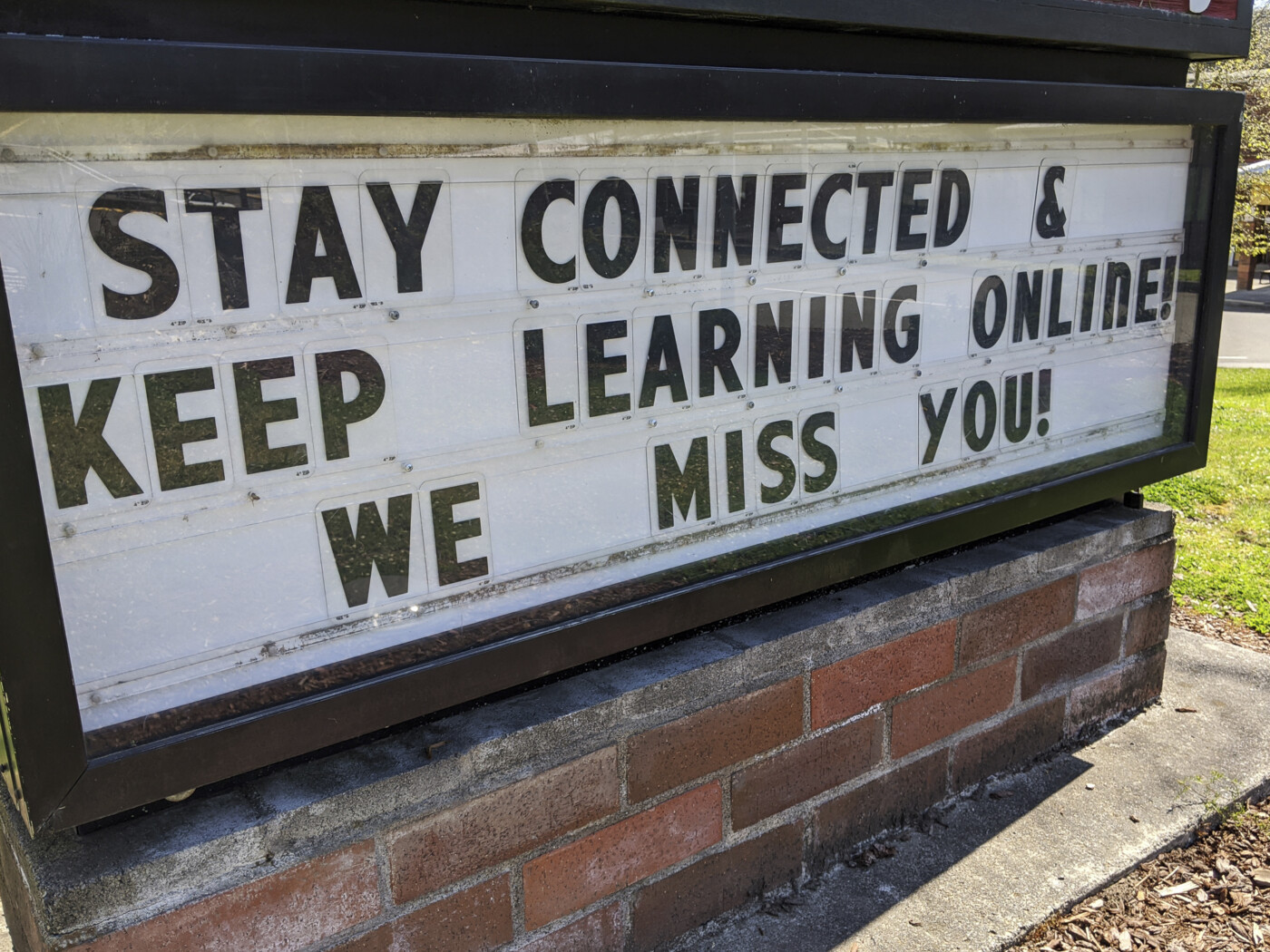

Education for at least 90% of the state will have to be held online. Schools cannot reopen unless their county’s coronavirus infections and hospitalizations are stable.

Gov. Gavin Newsom announced today that more than 5.5 million California students will not be allowed to attend school for in-person education this fall. Instead, all education for at least 90% of the state’s children must be held online.

Under the requirements, California school districts cannot reopen campuses until their counties stabilize coronavirus infections and hospitalizations.

The governor’s announcement follows weeks of pleas from school administrators for more direction on how to reopen schools. It will have an extraordinary impact on working parents and children, who must remain at home, as well as the state’s battered economy.

The decision marks the governor’s most forceful involvement in schools.

“Learning is non-negotiable. Schools must provide meaningful instruction during the pandemic whether they’re physically open or not. We all prefer in-class learning, but only if it can be done safely. I believe that as a parent,” Newsom said.

The mandate applies to private and public K-12 schools, he said.

Thirty-three out of California’s 58 counties — which encompasses about 90% of the state’s school children — are on the state’s watch list and do not comply with the infection benchmarks, so they will have to stay closed.

This includes all of Southern California and most of the Bay Area and Central Valley.

With some schools starting the new year as early as Aug. 3, it would be too late for most of them to switch gears for the fall if their counties do fall off the list.

Under the state’s new requirements, schools can offer in-person instruction only if their county has been removed from the state’s COVID-19 monitoring list for more than 14 days. Additionally, districts must test teachers for the coronavirus every other month.

Edel Maurin, a parent in the Inland Empire’s Corona-Norco Unified School District, said she and her husband juggled to keep her three sons occupied during the spring while they both worked remotely processing electronic medical records.

Maurin said she’s concerned for her oldest child, a rising second-grader, and hasn’t heard from his school about how they plan to do distance learning this fall. But, she added, the worries over the coronavirus and her kids’ safety are more pressing.

“I’m all for virtual learning if it has to come down to it, because for my husband and I, it’s safety first,” she said. “We won’t be able to live with ourselves if something ever happened.”

In the Tracy Unified School District in San Joaquin County, teacher Crystal Wong won’t be coming back and neither will her two high school-age children.

Prior to the governor’s announcement, Wong, who said she is at high risk from the virus, said she seriously considered taking a leave of absence or applying to teach remotely if asked to physically return to her classroom. Her county is on the watch list.

“I still want to help students learn and prepare for amazing futures,” Wong said. “This will not always be our reality.”

Most California districts had been planning to offer families a choice between distance learning and hybrid scheduling — where students alternate learning from home and in physical classrooms under social distancing practices.

But since late June, the potential for some semblance of in-person instruction have dramatically shifted in California as positive cases and COVID-19 hospitalizations surged in most areas of the state.

A small group of districts in some hard-hit regions told parents that they planned to start the 2020-21 school year under full-time distance learning. In the two weeks since then, Los Angeles and San Diego, the state’s largest districts, pivoted to a distance learning start and then the floodgates opened, with many of the state’s districts saying they will not reopen campuses in the fall.

As recently as Thursday night, some local school boards, such as San Ramon Valley Unified in the East Bay, that planned to offer in-person instruction convened emergency meetings to walk back those plans, noting that the governor’s expected announcement influenced decisions.

The San Ramon Valley school district had planned to offer parents and students a choice of in-person instruction. But several parents told the district in a survey that they were apprehensive about sending their children to school. About 70% of the district’s teachers told the union they felt unsafe about returning to classrooms.

“All of us want, in an ideal world, to be able to see our kids and our new students the first day of class just like any other year because building relationships is significantly easier that way,” said Lucien Martin, an English teacher at San Ramon Valley High School. “But I think as people are starting to get their feet wet with digging more into the side effects of all this and learning more, their opinions have shifted.”

“Learning is non-negotiable. Schools must provide meaningful instruction during the pandemic whether they’re physically open or not.“

Governor Gavin Newsom

Up until today’s state’s reopening requirements, local school districts have been strategizing how to reopen schools this fall. This has triggered an inconsistent patchwork of plans in which some local districts planned to remain physically closed while neighboring districts were adamant on reopening. In Fresno County, for example, while some districts such as Central Unified delayed physically reopening campuses, the school board for nearby Clovis Unified voted to allow parents to choose between full-time distance learning and a full week of in-person instruction.

And although the California Department of Public Health and Department of Education each put out guidance in early June on safety precautions for reopening, county officials also put out guidance sending conflicting messages to schools. For example, while some counties suggested their schools space student desks six feet apart and require that students and teachers wear face coverings, other counties relaxed requirements on spacing.

In the state’s most prominent example, the board of the Orange County Department of Education suggested that school districts not require face coverings or any social distancing in schools. Local administrators had been asking for standardized criteria or metrics to guide local decisions for reopening.

The state’s new requirements aim to settle some of the confusion that’s surfaced around the safety precautions once students and teachers are allowed to be on physical campuses.

When their schools reopen, California students in grades 3-12 will be required to wear face coverings and will be excluded from in-person instruction if they refuse to comply. The guidance suggests younger students wear face coverings, but does not mandate it. Adults in the schools will have to maintain six feet of distance from kids and colleagues.

School campuses that are open for business will have to shut down again if more than 5% of students and staff test positive for the virus.

In meetings this week with state officials, many county school superintendents and public health directors vented frustrations that they did not have enough guidance from the state, leading to mass confusion among parents, students and educators.

“If the state doesn’t give us that guidance, then you’re back to the same situation where some (schools) will start coming back, some won’t start coming back, and we’ll be in this mixed messaging again to the community,” Steve Herrington, Sonoma County’s superintendent told CalMatters before Newsom’s announcement.

A wholesale shift to distance learning will challenge many students and teachers across the state. As of June, the state estimated that schools needed 765,000 computers for students and teachers. Hundreds of thousands of students don’t have reliable internet connectivity.

Many school districts have said they’ve worked to improve the quality of distance learning that students received — or failed to receive for students who disconnected from their schools, promising parents more rigorous offerings than last semester.

The state budget Newsom signed included new standards for distance learning, such as requirements that schools connect with their kids every school day. Though the budget does not spell out requirements for the live, synchronous instruction that many parents are seeking, the governor said the state expects more from schools this fall.

“I want to see that interaction with teachers,” Newsom said. “I want to see that interaction with students, and I also want to see it rigorous, I also want to see it challenging. “

Janelle Marie Salanga and Stephen Council contributed to this report.