Voting rights are under attack in the U.S. and California’s representation at the federal level is at risk despite the state’s significant voter outreach efforts, warns Ari Berman, the author of a book on voting rights who will be speaking in Oakland this Saturday, September 28.

In a recent interview, Berman said his lecture at the Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Center will touch on new efforts at voter suppression, gerrymandering and the 2020 census.

Berman warns that recent erosions of voting rights threaten the basis of the U.S. democracy. While all eyes will be on the next presidential election in 2020, Berman argues that state legislative races and the next Census will have a larger impact on the long-term health of American democracy.

The current structure — including the Electoral College and the use of gerrymandering — has left the country in a position where a minority can rule exclusively. In fact, Republicans already control the presidency and Senate despite Democratic candidates receiving more votes. As recently as 2012, Republicans controlled the House of Representatives, despite receiving fewer votes overall than Democrats.

“It’s just absolutely staggering that one party can control all three branches of government without actually getting a majority of votes with any of them,” Berman said.

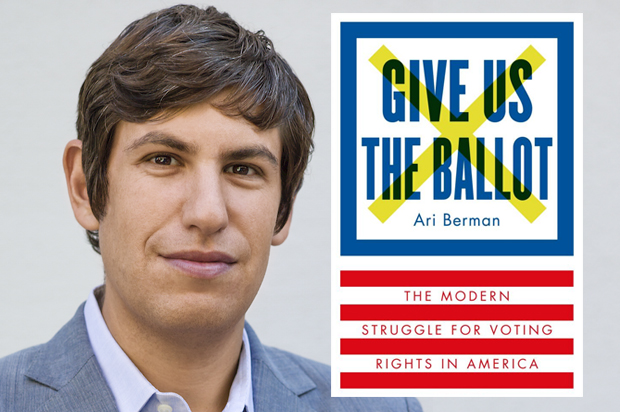

Berman’s 2015 book, “Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America,” is a history of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, landmark legislation intended to end systemic disenfranchisement of racial minorities.

He said that the Voting Rights Act was gutted in 2013 by the Supreme Court, which overturned a requirement that certain southern states and local governments with a history of discrimination obtain federal approval before changing their voting practices. The ruling, he said, has directly impacted elections, including in Georgia, where Democrat Stacey Abrams narrowly lost the gubernatorial race to Republican Brian Kemp, who was Secretary of State at the time and oversaw the election procedures. Abrams did not concede the election and sued the state, citing allegations of voter suppression. “There was just so many problems with voting in that state,” Berman said, citing the closure of more than 200 polling stations, tens of thousands of people purged from voter rolls, and long lines to vote in majority black areas.

All the changes Kemp made would previously have needed federal approval. But since the 2013 Supreme Court ruling, they didn’t, and they can only be challenged after the fact, Berman said. There have been similar new restrictions in other states covered under the Voting Rights Act, including Alabama, North Carolina and Texas.

The principal argument that Republicans make for more voting restrictions is that they are combating voter fraud, Berman said, but the most prominent recent example of election fraud was on behalf of Republicans in North Carolina, where mishandling of absentee ballots by a party operative led to criminal charges.

“Voter fraud is a very small problem in American elections, and usually you get caught,” Berman said. “Sort of ironically it was the Republicans who were doing the election fraud even though they were saying over and over it was the Democrats that were committing fraud.”

Berman said he doesn’t give any credence to President Donald Trump’s baseless claim that millions of undocumented immigrants voted in California’s last election. It “doesn’t make a whole lot of sense why someone who was undocumented would risk deportation to commit voter fraud,” he said.

In fact, Berman argues that California is going in the right direction compared to the southern states, with a number of policies that make the voting process fairer and easier such as non-partisan redistricting, automatic registration, Election Day registration and vote by mail. “In my view all of those things are much better than what we’re seeing in states that are passing these restrictions,” Berman said.

But California is facing some external challenges in its efforts toward fair elections, most significantly with the Census, which defines how political power is allocated in the U.S. California in particular can be a difficult state to count, Berman said.

“It’s so big, it’s so diverse, there’s so many different communities who might be fearful of the federal government,” Berman said. “They have the sense that the Census is just for American citizens.”

Complicating efforts for an accurate count is Trump’s public calls to put a citizenship question on the Census. He was eventually rebuffed by the Supreme Court, but it may have a chilling effect regardless for immigrant populations. “The risk is the damage was already done. People heard that they wanted to have their citizenship information on the census,” Berman said.

“The fear is the undercount is going to get much worse and Trump was specifically singling out communities in California by trying to get this question on.”

Author Ari Berman

Without an accurate count, California could find its federal political power diluted.

To combat it, the state is putting millions of dollars into bolstering efforts to conduct the Census. The state allocated $90 million from the 2017-2018 budget for the 2020 Census and then-Gov. Jerry Brown formed a Complete Count Committee in April 2018. The count in the Census will inform the next round of redistricting in 2021, which will be carried out by state legislatures.

“We’re going to have wildly different outcomes depending on who controls the state,” Berman said. “State legislative bodies will have more of an impact on voting rights than who the next president will be.” Some states have non-partisan methods of drawing districts, but others divide voters in ways that are “deeply unfair,” Berman said. Yet the Supreme Court recently ruled that federal courts can’t review partisan maps, so it’s up to state courts to hold legislators accountable. That too will likely vary widely.

“Some maps will be so unfair they will lock in power for the next decade,” Berman said. “The science of redistricting has gotten so advanced that you can lock in power like you never have before. You only get one crack at this.”

Berman’s lecture at the Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Center will begin at 7 p.m. Saturday. He will be introduced by Alameda County Supervisor Nate Miley.

SEE RELATED