Two Piedmonters — Iturralde (seen above) and Weaver — are among the experts weighing in on the embattled but dominant literacy instruction model in schools nationwide.

An EdSource special report

When Esti Iturralde’s daughter Winnie was in first grade, the girl struggled with learning to read. Like most parents, Iturralde blamed herself at first.

“I thought there was something wrong with my kid. I thought there was something wrong with us,” said the Bay Area mother of two. “I just couldn’t really understand what was going on.”

The teacher consoled that Winnie just wasn’t ready, but Iturralde, a psychologist, began to suspect the type of reading instruction was holding her child back.

“Her teacher was wonderful,” she said. “She created a really vibrant classroom for literacy with beautiful read-alouds and publishing parties. She involved families in reading to the children. So I thought, what’s missing here?”

Iturralde ended up getting a crash course in the science of reading. Part of what she learned is that the human brain is wired to speak but not to read, because written language remains a relatively new invention in human history.

Many educators, however, believe that reading comes naturally, like talking, if the child is immersed in a language-rich environment. That’s why Winnie didn’t get enough explicit instruction in school about phonics, the link between letters and sounds.

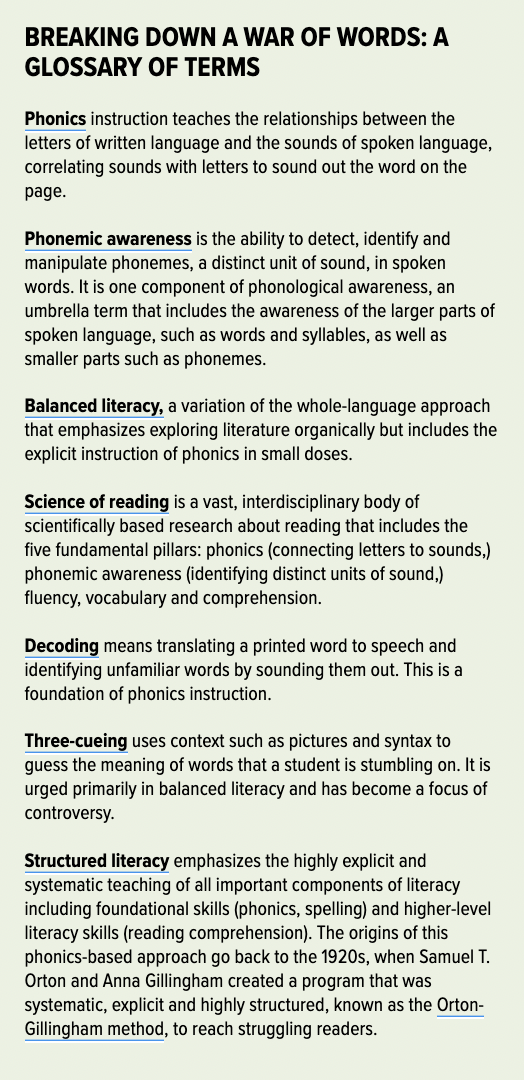

The reading wars

Phonics, a method of teaching reading by correlating sounds with letters, may not seem like a controversial concept, but it’s an anathema in some academic circles. Many teachers dismiss the practice of sounding out words as old-fashioned drudgery that prevents children from loving literature.

This view of reading harks back to Horace Mann, the father of American public education, who attacked teaching phonics and the alphabet in the 1800s. He believed children should learn to recognize whole words, one of the keystones of the “whole language” movement, which set the foundation for the “balanced literacy” approach used in many California schools from one end of the state to the other.

For the record, balanced literacy touches on phonics, experts say, but it does not give it the laser focus of a “structured literacy” program, which is rooted in phonics and other fundamentals. It is also a method steeped in the science of reading.

“There’s a phobia about breaking down words into little parts. If you boil it down to the letters on the page, they fear, certain magic may be lost,” said Iturralde. “There’s also the belief that you have to let children discover things for themselves.”

The philosophical tug-of-war between teaching phonics, how to sound it out, and teaching meaning, how to think it through, persists despite exhaustive research suggesting that most children must be explicitly taught how to connect sounds with letters. To make matters worse, most of this is an insider debate that most parents and caregivers know little about. Even the terminology, from balanced literacy to structured literacy, seems designed to scare off the uninitiated.

How many children have been collateral damage in this war of words? The pendulum has been swinging between these competing approaches for decades, despite a body of research on the subject that was codified as far back as 1999 when Congress convened the National Reading Panel.

Some call this battle over reading strategy, “the reading wars.” It’s a conflict that is resurfacing in California and inciting change across the country.

This ongoing EdSource series will do a deep dive into the scope of the literacy crisis in California, digging into emerging research, state policy, a groundbreaking lawsuit, teacher training and bilingual issues, to assess just how much is at stake in a state that fails to teach more than half of its children how to read.

“A generation of kids got sold down the river,” said Austin Beutner, a former Los Angeles Unified superintendent. “They have no grounding in the fundamentals of phonics and decoding. Less than half the kids can read. That’s staggering to me. How can we find that acceptable?”

With New York City and several states shifting their approach and balanced literacy guru Lucy Calkins admitting to flaws in her influential curriculum, “Units of Study,” this academic debate is coming to a head in California. Educators and policymakers are at odds over myriad thorny issues, from battles over curricula and the politics of teacher credentialing to a newly-funded program to place reading coaches into high-need schools as the literacy crisis deepens in the wake of the pandemic. The central question emerges: Why do so many children struggle to read, and how can their teachers and caregivers help them?

“The literacy crisis in our country is not because kids can’t learn to read,” said Jessica Reid Sliwerski, a literacy expert and founder of Open Up Resources, a nonprofit that offers accessible curricula. “The problem is that a huge swath of our population of young children never gets access to the type of instruction they need. They never get the opportunity to learn how to crack the code.”

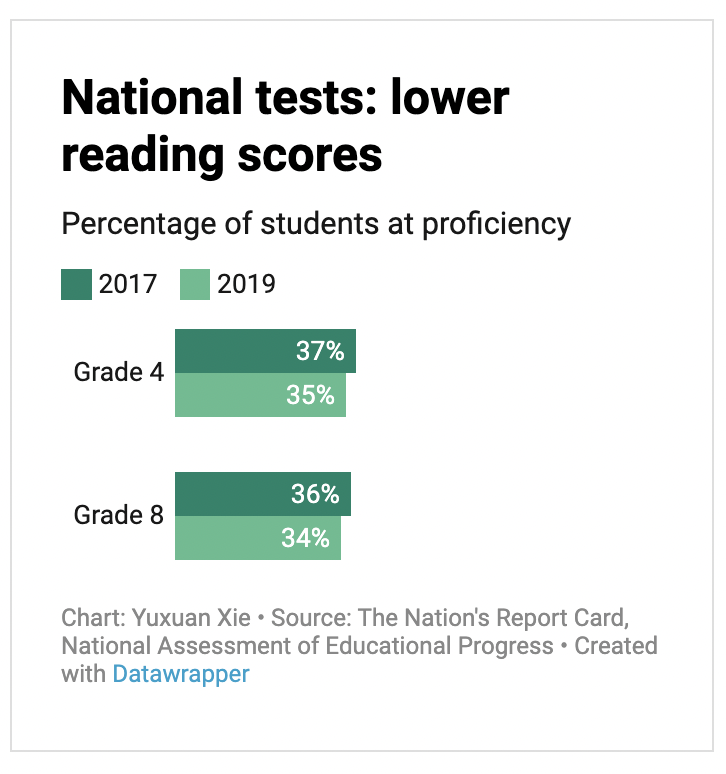

Only a third of American students were found proficient in reading, according to 2019 scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as NAEP, the Nation’s Report Card. And that is before the pandemic disrupted schooling, sending test scores into a tailspin.

“Our hair should be on fire. And the way in which we douse that fire is by getting really, really clear about how the science of reading can equip us to promote that liberatory outcome that reading can be,” said Zaretta Hammond, author of “Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain.” “Reading is how the brain levels up.”

In California, 48.5% of the state’s third-graders tested at grade level or above in English language arts in 2019 before the pandemic disrupted testing. (Non-English learner students tested 57% at grade level.) Students who aren’t reading at grade level by the third grade will struggle to catch up throughout their educational career, research suggests, quickly falling behind their classmates and widening the achievement gap.

How does the brain learn to read?

One of the key concepts here is that lessons in phonics and other reading fundamentals help change the circuitry of the brain, experts say, forging pathways between the parts of the brain that interpret the auditory and the visual.

When a child learns to read, as neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, author of “Reading in the Brain,” puts it, the brain creates an “interface between your vision system in your brain and your spoken language system.”

That’s why children must be taught how to link the sounds of the words with the symbols on the page, experts say, how to connect speech to print. These neural pathways are like superhighways that become smoother and wider through use, experts say. Helping children forge these connections efficiently is the core of what experts call “structured literacy,” a phonics-based approach.

“How kids learn is settled science, but we have this big implementation gap from research to practice, getting the knowledge to the classrooms,” said Becky Sullivan, a literacy expert at the Sacramento County Office of Education.

“We basically have 360 days to get it right. You have kindergarten and first grade to get kids reading. … You have got to get it done, or you set your kids up for an intervention situation.”

The pillars of structured literacy instruction are often defined as phonics (connecting letters to sounds,) phonemic awareness (identifying distinct units of sound,) fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Without a firm grounding in these foundational lessons, experts say, many children flounder.

Iturralde, who has a doctorate in behavioral science, conducted some experiments with her first grader, dubbed the Purple Challenge, to see if Winnie would blossom with more phonics, which she did. But she is quick to point out that she lays no blame at the feet of teachers, who have little control over curriculum and strategy.

Teachers at a loss

In fact, many teachers, unaware of the compelling brain research, do not realize that skimping on phonics and other fundamentals may come at a cost. While some children will thrive anyway, experts say, others will falter unnecessarily.

It’s only by looking back on their experiences with struggling readers that many teachers have a light bulb moment. Many say they will never forget the children they tried, and failed, to help because they didn’t have the expertise they needed.

“I taught reading wholeheartedly and with a lot of gusto. I tried my hardest, but it was not systematic, it was not explicit,” said Monica Ng, a former kindergarten teacher turned educational consultant. “It was very sad because there were kids who were really struggling to read, and I remember saying to their families, ‘I don’t know what I can do to help you.’”

Sabrina Causey, a first grade teacher at Oakland’s Markham Elementary, recalls going home and crying after a long day of trying to teach with a balanced literacy curriculum, which she now believes lacked enough phonics to be effective.

“I was trying to teach the lessons, but they didn’t make sense,” said Causey. “For instance, I taught lessons in how to ‘scoop up’ words, but the kids in my class didn’t know letters or sounds. These kids had no basic skills. So I had one kid who could read that year.”

One of the most controversial practices in balanced literacy is “three-cueing,” which teaches children to guess at words. When faced with a hard word, like purple, Winnie had been taught to look for contextual clues, such as illustrations, instead of sounding out the word. Take the pictures away and she stumbled. That’s why champions of structured literacy put the words first.

“The biggest problem we have is that teachers haven’t been taught how the brain works,” said Nancy Cushen White, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California at San Francisco and a reading specialist. “Fifty years ago, it was understandable, but there’s really no excuse for it now. And the worst part is the teachers are working just as hard. Teachers will say, ‘Why didn’t somebody tell me this 10 years ago?’”

Critics of structured literacy, however, feel the phonics-based philosophy is too reductive. They worry that it’s a series of endless “drill and kill” exercises that will diminish the joy of reading.

Champions counter that if a child doesn’t get firmly grounded in the fundamentals right off the bat, they may never get to fluency. Children run the risk of falling so far behind that they never master the deep comprehension that is mandatory in later grades. The sooner children can master the fundamentals, they say, the sooner they can immerse themselves in the splendors of great literature.

The secret is that once you get the basics baked into your brain, experts say, reading feels effortless and automatic. The pleasure of reading is the endgame. Phonics is just the warmup.

The reading wars assume a dichotomy between foundational skills and rich comprehension that doesn’t exist, some experts say. Instead, they are entwined like the braided strands of a rope, growing stronger with every additional thread, as the metaphor of Scarborough’s Reading Rope illustrates. Put simply, you have to be able to read skillfully before you can think deeply about what you’ve read.

“It’s just like building a house,” said Carol Tolman, a literacy expert and co-author of Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS, a science-of-reading-based training for teachers. “If you build a foundation with a crack and you leave that crack, the first floor is going to be a little shaky.”

Of course, children have varying needs, but only about 5-10% of children will learn to read without very explicit instruction, some experts say. These effortless readers may have given rise to the notion that learning to read should come naturally, but that is not the case for most.

While about 35% of children will learn to read no matter how they are taught, according to many experts, about 40-45% will struggle without clear and consistent lessons in the fundamentals. The remaining 10-15% qualify as dyslexic, and these children benefit the most from a structured literacy program.

“From an equity standpoint, foundational skills are something that is good for all kids,” says Sliwerski, who also created Ignite Reading, which specializes in Zoom-based tutoring, “but they are absolutely essential for the vast majority of the children.”

Children who struggle with reading often internalize feelings of failure that may set the tone for their academic career, and time-pressed parents blame themselves, experts say, instead of realizing they are snarled in a systemic failure to teach reading effectively.

“There’s an assumption on the part of the school that if students are not reading well, that’s the kid’s problem,” said Ng, the teacher turned consultant. “It’s a kid-level problem and not an instructional problem.”

Winnie, for her part, became a huge fan of phonics, zooming from reading level B (a kindergarten level) to level O (a second-grade level) by the end of first grade. She was so excited when her mom ordered a phonics book that she took a selfie with it. Now going into third grade, she’s an avid reader, with a special fondness for the Harry Potter canon.

“I’m proud of her,” said Iturralde. “She talks about loving to read and it being her favorite part of school.”

Unfortunately, not everyone has a highly educated parent like Iturralde around to help them connect the dots. Most families can’t afford a private tutor. That leaves far too many children out in the cold, educators say.

“If the teachers don’t change the practice in the classroom,” said Timothy Shanahan, a literacy expert and professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, “you can’t possibly expect reading achievement to go up.”

Is the tide turning?

While many California school districts use a balanced literacy approach, a compromise between whole-language, which focuses on whole words, and structured literacy, which focuses on phonics, change is underway in many quarters.

New York City will require all elementary schools to adopt a phonics-based reading program in the coming school year. Oakland Unified began making that switch last year.

Many states are also considering legislation that would require teacher preparation to include the science of reading. A few states, such as Louisiana and Arkansas, have recently banned three-cueing, which encourages students to rely on clues, such as pictures, to guess the word. In California, SB 488 requires newly credentialed teachers to receive training in the science of reading, but implementation remains a sticking point. Changing classroom practice by virtue of legislation is no mean feat.

“Given flexibility, teacher preparation programs will change little,” said Todd Collins, a Palo Alto school board member and an organizer of the California Reading Coalition, a literacy advocacy group. “And then, even if the standards are clear, there is a major gap between the rules and what actually happens.”

Issues of quality control and consistency dog the teacher training sphere as a whole, experts say.

“There are about 1,500 teacher training organizations in the U.S. and they are poorly monitored and poorly supervised,” said Shanahan, founding director of the UIC Center for Literacy. “We’re putting resources in, but our bucket has a hole in it.”

Meanwhile, in California, the governor and the Legislature are setting aside $250 million for reading specialists in the highest poverty schools in the 2022-23 budget, with $15 million more to train these coaches in evidence-based literacy strategies. State Superintendent Tony Thurmond has launched a literacy initiative to get all third-grade students reading by 2026, but he has also said he does not support a comprehensive statewide strategy, rejecting “a one-size-fits-all approach.”

Without clear guidance, schools and districts often pivot from one approach to another, experts say, creating confusion for students and teachers alike. Oakland and New York City have both flipped back and forth in recent years.

An issue of equity

Some advocates are calling for more accountability. They believe school districts have made mistakes for which students have paid the price. The ramifications of this failure, they warn, include a generation of young people who can’t compete in a knowledge-based economy.

“This is a civil rights issue because people are being systematically denied access to their civil liberties and their opportunities because they’re illiterate,” said Kareem Weaver, member of the Oakland NAACP Education Committee and co-founder of the literacy advocacy group FULCRUM. “This is a social justice issue.” Weaver is prominently featured in the documentary “The Right to Read.”

The key question now, some experts say, is how to build a consensus for change. Bridging the gap between scientists and educators, each laboring in their own silo, may strike at the core of the problem, as Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, argues in “Language at the Speed of Sight.”

“The gulf between science and education has been harmful,” according to Seidenberg. “A look at the science reveals that the methods commonly used to teach children are inconsistent with basic facts about human cognition and development and so make reading more difficult than it should be. They inadvertently place many children at risk for reading failure.”

The need to connect high-level research to classroom practice drives Margaret Goldberg, the literacy coach at Nystrom Elementary in West Contra Costa. She also collaborated with Seidenberg on a presentation about guiding principles to help educators design evidence-based curricula for the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference.

“I try to talk teacher-to-teacher in a way that makes teachers curious about the research,” said Goldberg, the co-founder of the Right to Read Project, a group of teachers, researchers, and activists. “A lot of us were underserved by our teacher preparation and underserved by our curriculum. There are a lot of conflicting messages out there about what we’re supposed to do and why.”

Reading research was the North Star for Kymyona Burk, a principal architect of Mississippi’s reading program. The poorest state in the nation, Mississippi was the only state to post significant gains on the NAEP in 2019. That turnaround was driven by a statewide literacy push that revolved around teacher training.

“All children deserve teachers who have been trained in the science of reading,” said Burk, who is now policy director for early literacy at the Foundation for Excellence in Education, an education think tank. “We not only said we need children reading by the end of third grade, we also said we’re going to help you get there. We put literacy coaches in our lowest-performing schools, and we provided professional development to our teachers.”

Burk describes illiteracy as one of the most solvable issues of our time, but you can’t teach what you don’t know. In Mississippi, every teacher goes through LETRS, a science-of-reading-based training. Still, even statewide strategies and teacher training are not magic bullets, experts warn.

“It’s not something that’s easy to learn,” said Dale Webster, vice president of language and literacy at CORE, a nonprofit education consulting organization.

“It’s not, you get a little course in teaching reading, and then you get a program, and then you just go to town. It takes a long time to learn the skills, and teachers need ongoing support to be able to do it effectively.”

There’s also the issue of curriculum whiplash, experts say. Teachers who have been tugged back and forth by the reading wars may be resistant to yet another wave of change.

“You’re asking someone to change their identity,” said Aaron Bouie III, executive director of PreK-5 curriculum in Ohio’s Youngstown City School District. “It is not easy to change a mindset. There will be tears. It’s not for the faint of heart.”

However, grassroots awareness of the issue is growing, reading advocates say, often fueled by social media conversations between parents, teachers and experts. The Facebook group “Science of Reading: What I Should Have Learned in College” now has roughly 170,000 members. There’s a Science of Reading corner on TikTok with short how-to videos. On Twitter, the hashtag #ScienceofReading is a hotbed of discourse.

Adding to that awareness was American Public Media education reporter Emily Hanford, who challenged the educational establishment by asking why educators were ignoring scientific research in the teaching of reading in a probing series of stories beginning in 2018.

One major sign of the times is that Calkins, a titan in the world of balanced literacy and a professor of education at Columbia University, has revised some of her philosophy, which largely viewed children as natural-born readers. Amid a rising chorus of criticism, she is revising her materials to acknowledge the science of reading.

While the launch of the revised curriculum has been delayed, and details remain fluid, the reboot appears to downplay three-cueing, a mainstay of balanced literacy, include easy-to-read “decodable” books, and encourage sounding out words.

“When a child is reading a sentence such as, “It was cold, so I put on my jacket,” and the child gets stuck on jacket,” Calkins writes on her publisher’s blog. “We now suggest the teacher nudge by saying, “Look at the letters, have a go with that word,” rather than saying, “Think about what’s happening. What might the boy put on?”

This marks a clear shift in focus from the context to the text, where many argue it should always have been.

“To actually have a leader at an Ivy League institution that’s been held up as a kind of pinnacle of teacher preparation say, ‘I learned a lot of stuff in the past five years,’ that’s a big deal,” said Goldberg, who has penned several open letters to Calkins. “The research has been around for decades, and you recently learned about it as a result of public outcry?”

This high-profile pivot in thinking about learning to read, coupled with the disruptions wrought by the pandemic, may be leading the education world to a watershed moment, some say, a way to move beyond the latest skirmish in the reading wars.

“We can seize this opportunity to get really effective instruction in place,” said Goldberg. “If we can allow teachers to have access to the information they need about how the human brain develops, how learning is best accelerated by explicit teaching, then teachers can be responsive to the tactic that will get the most kids, the furthest, the fastest.”