The job of the state superintendent of public instruction may be very different a year from now.

Last month, the nonprofit research organization PACE (Policy Analysis for California Education) released a report on school governance that recommended transferring the California Department of Education’s operations from the state superintendent to the governor and the State Board of Education, whose members are appointed by the governor.

Gov. Gavin Newsom picked up the idea and is proposing to implement it in the 2026-27 budget.

Relieved of management responsibilities, state superintendents would continue to advocate for issues they campaigned on but take on different missions: Newsom suggested the superintendent could serve as a statewide education coordinator, ensuring smoother transitions from early education through college and career preparation. The PACE report proposed that the superintendent become an independent evaluator of TK-12 programs and an ombudsperson for voters.

Language in the governor’s education trailer bill, due by Feb. 3, will flesh out the proposal. There could be hearings and revisions before the state Legislature adopts the budget and then the trailer bill in late June.

“There’s been confusion around who’s responsible for education in the state,” said Julie Marsh, a professor of education policy at USC and co-author of the PACE report. “Putting the department under the state board and governor and removing electoral pressures would create clearer lines of authority and accountability.”

The changes would take effect under the next governor and state superintendent elected in November. Current Superintendent Tony Thurmond, who opposed the plan, is running for governor.

Newsom’s and PACE’s proposals have prompted many questions: What are the superintendent’s current duties? Is there a need for structural changes, and what could the overhaul mean for parents and students?

Who created the state superintendent’s position?

Voters did in the 1849 California Constitution to oversee the state’s “common schools.” Four years later, Gov. John Bigler unsuccessfully sought to abolish it. Since then, lawmakers and educators have debated how much power the office should hold. The constitution said little about the role, leaving most responsibilities for legislators to define. The superintendent is one of eight statewide offices, elected on a nonpartisan basis and limited to two four-year terms.

Do most states elect their top education official?

California is one of 12 states that elect their top school official. Under Newsom’s proposal, California would continue to do so but would join 20 states where a state board selects the chief school officer who runs the education department, according to PACE.

What are the state superintendent’s official duties?

Making policy that is not spelled out in the constitution or statutes is a sideshow. The biggest job is running the Department of Education, which includes:

- Monitoring school districts’ compliance with state and federal programs, grants;

- Disbursing funding and issuing guidelines for education programs like transitional kindergarten;

- Executing policies, regulations, and academic standards adopted by the State Board of Education;

- Deciding appeals of discrimination complaints and of subpar school conditions;

- Collecting data on district spending and student performance;

- Sharing responsibilities with county offices of education and the semi-independent California Collaborative for Educational Excellence for helping districts improve;

- Running two schools for deaf students and a state school for blind students;

- Appointing state trustees for insolvent districts and monitoring their recovery.

Are there other responsibilities?

The state superintendent also serves on numerous boards, including as a non-voting member of the retirement fund CalSTRS, the UC Board of Regents and the CSU Board of Trustees, and as a voting member of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing and the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence. Newsom proposes making the superintendent a voting member of the state board and the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges system.

How big is the department?

The department employs 2,501 people, fewer than eight years ago, despite increased responsibilities. Of the 1,571 employees at the department’s Sacramento headquarters, 56% are either fully or partially federally funded to monitor compliance with federal programs, limiting their flexibility.

Is the department underfunded?

A 2018 study concluded that the department is understaffed and underfunded compared with departments in other states, hampering its ability to directly assist districts. Salaries, tied to the state civil service scale, are noncompetitive compared with top-level professionals in districts in other states, contributing to retention problems, it said.

That’s still the case.

The wording of Proposition 98, which determines how much state revenue goes to TK-12 and community colleges, prohibits using any Prop. 98 money (about $120 billion next year) on the department. It must compete with prisons, higher education and Medi-Cal for a piece of the remaining general fund. Governors haven’t lobbied hard for more, since they don’t control the department.

The result has been workarounds undercutting the department’s authority. Since county offices of education are funded by Prop. 98 and can pay better, the Legislature has routed grant programs to them and the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence. As an agency working with districts on innovation and improvement, it rightly could have been an arm of the department.

Shifting the department to the state board and governor won’t shift funding to Prop. 98, but Marsh assumes governors would pursue more general fund money once they run the department.

Newsom has proposed a $299 million budget for the department in 2026-27, up only 1.7% ($5.5 million) from this year and 9% above 2018-19.

The rationale for an overhaul

Commissions and studies directed by the Legislature and academics have consistently made the same argument for decades. Summarizing five reports published over 25 years, the Legislative Analyst’s Office wrote in 2018, “All studies recommended making the governor the clear head of executive functions.”

There are three reasons, according to advocates:

Clarify who’s in charge. With program oversight and improvement efforts spread among the state superintendent, the state board, the governor and various state and county agencies, it’s unclear who’s responsible for the big vision of education and accountable for performance. The PACE report concluded, “This ambiguity in decision-making creates a system where responsibility is diffuse, and no person or agency can be held accountable.”

By centralizing operations under the Department of Education, reporting to the governor and the state board, the buck would stop with them.

Professionalize management. Thurmond and his three predecessors — Tom Torlakson, Jack O’Connell and Delaine Eastin — were veteran legislators with no experience running a complex education system. They ran on their positions, not their management skills; once elected, they focused on meeting key constituents, creating task forces and corralling legislators to sponsor bills on their behalf.

“An elected state superintendent’s role is inherently different from the administrative leadership needed for system alignment and agency management,” said Lupita Cortez Alcalá, the executive director of PACE, who previously served three state superintendents in key management positions. “You need someone with operational authority who understands not only education systems, but has the experience to manage an agency to be of service to other agencies.”

End the disconnect between making and implementing policies. Newsom has rushed through landmark programs in the past six years, using billions of revenue from a booming tech sector: community schools, transitional kindergarten, after-school and summer school for all elementary students.

“The investments have been amazingly good; where things have fallen short is the implementation,” Alcalá said.

Added Marsh, the USC professor: “The governor doesn’t really feel responsible to come up with an implementation plan when he does a big initiative like community schools, because he doesn’t have any control over it.”

What difference might realignment make for parents and students?

The road from the Capitol to the classroom is long and needlessly confusing. Clear directions and smart planning would help, advocates say.

Yolie Flores, the president and CEO of the Los Angeles-based nonprofit Families In Schools, said that families and educators would finally “see a clear through line as to who is responsible for their children’s education.”

“When districts spend less time navigating bureaucratic complexity,” she said, “they spend more time improving instruction. Families need a system they can understand with clear and usable guidance for educators and families — whether dual language access or family engagement.”

Flores is also enthusiastic about the potential to shift the role of the state superintendent to the “state’s lead equity advocate.” That person could “use the bully pulpit to spotlight gaps, for example, in early literacy, dual language access, special education, and family engagement.”

“This is especially important in a local-control state like California,” she said. “Local control without strong state stewardship can unintentionally widen inequities.”

Who opposes the realignment?

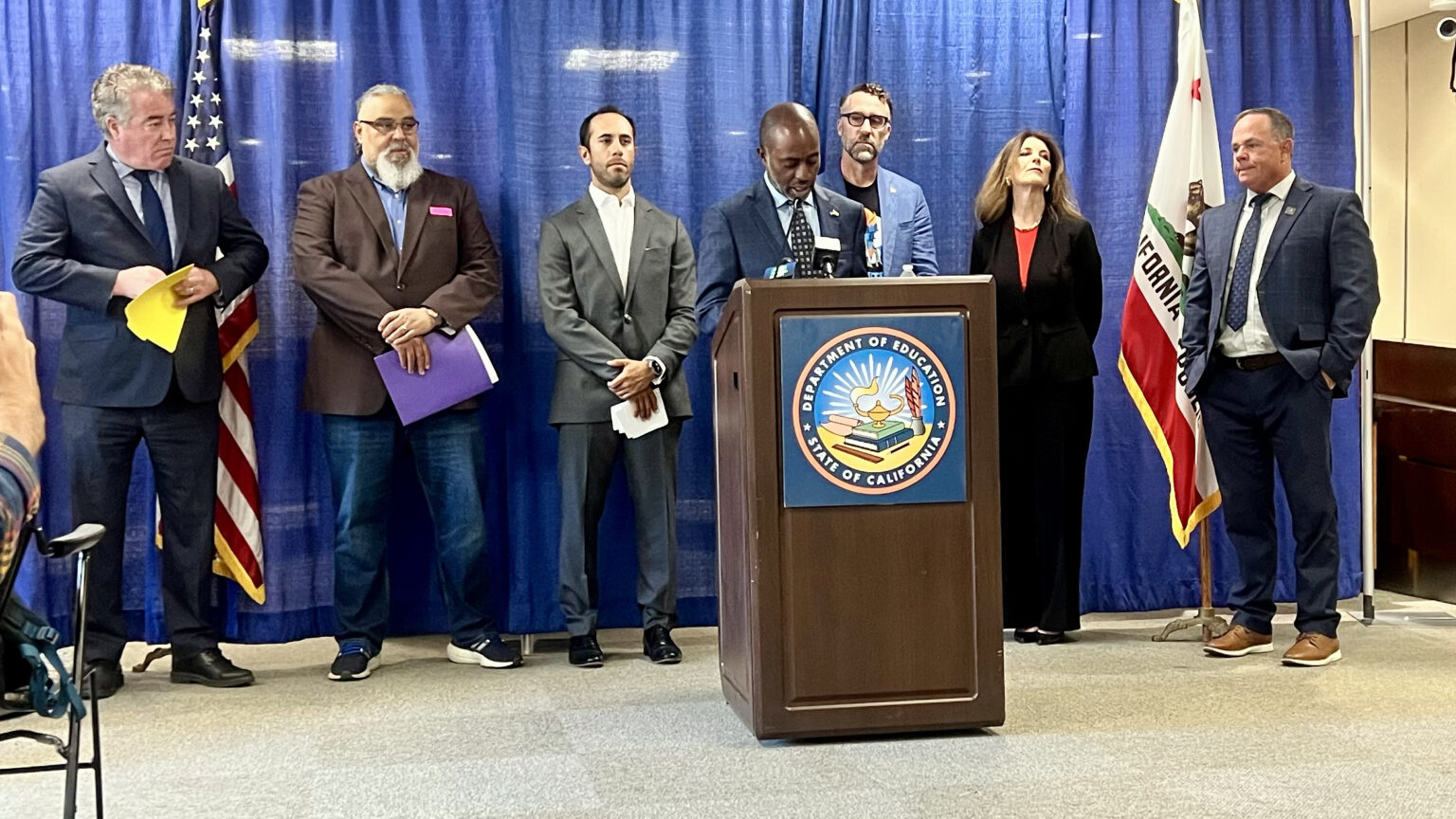

Newsom secured support from the student advocacy group Children Now and key education groups, which endorsed the concept while waiting for the details.

Thurmond is the most outspoken opponent, so far. Stating that neither he nor the department was consulted about the proposal, he said it “doesn’t establish any structures proven to move the needle on student outcomes and instead shifts authority to implement TK-12 education programs away from the official who California voters have elected to lead our state’s public schools.”

One of the seven superintendent candidates to succeed Thurmond, former state Sen. Josh Newman, who chaired the Senate Education Committee, agreed that his job should be diminished. “Whoever wins that position — whether another candidate or I — should do the job well and work to replace it with a system that better serves California, its students, its teachers and its future,” he wrote in the Los Angeles Times.

Other candidates agreed with Thurmond. Richard Barrera, the president of the San Diego Unified School District board and a senior adviser to Thurmond, said the superintendent’s role should be strengthened to fix any structural problems, not weakened.

And Nichelle Henderson, a teacher educator in the California State University system and trustee of the Los Angeles Community College District, wrote that the real problem is not governance fragmentation but “capacity,” as the PACE report acknowledged. “Years of underfunding and instability have stretched the California Department of Education thin, shifting its focus toward paperwork and compliance rather than helping schools improve. Changing who holds power at the top does nothing to address that.”