After Renee Good was shot and killed by a federal immigration agent in Minneapolis, Watsonville High School teacher Sarah Clark’s ninth grade students had a lot of questions. What precipitated the interaction? Was she yelling at them? Was she aggressive? Was she rude? Can we film immigration agents? Will we be arrested if we do?

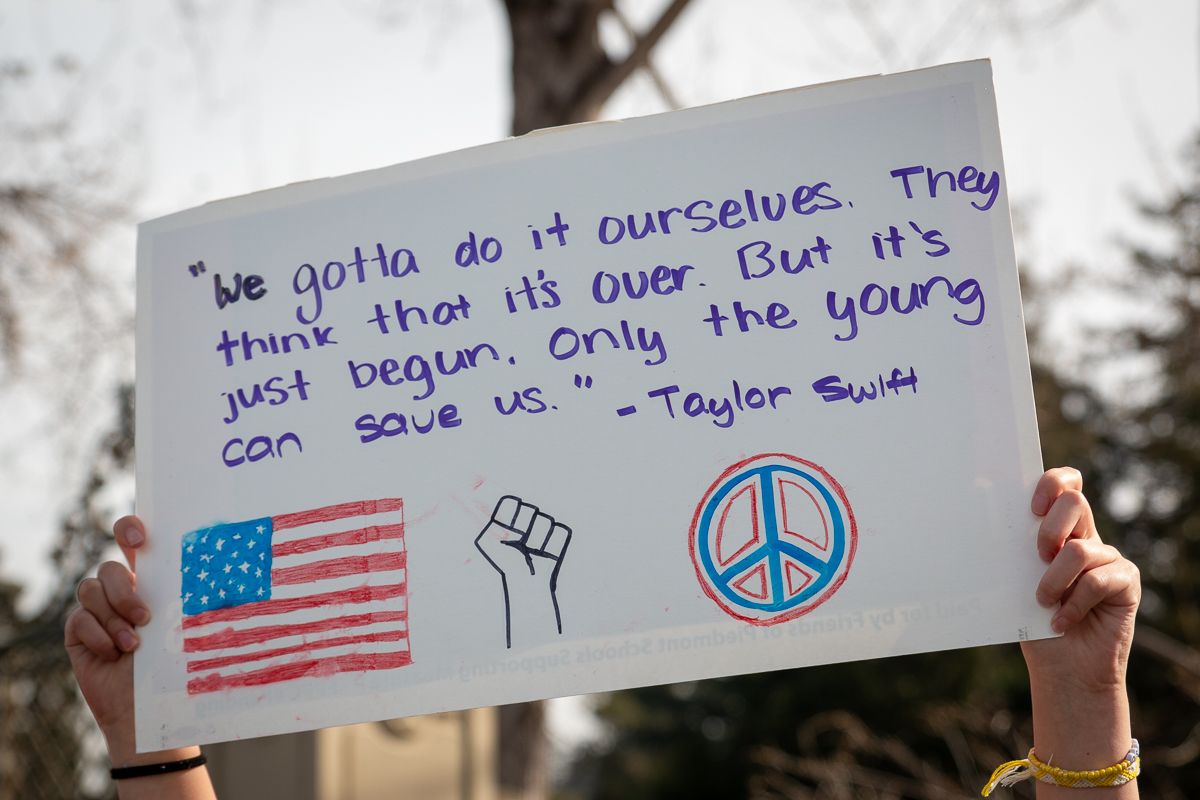

The fatal shootings of Good and, a few weeks later, Alex Pretti, by federal officers have sparked nationwide outrage and led to student walkouts in California. In the aftermath, teachers in several districts said they have been navigating difficult conversations about the legality of federal immigration agents’ use of force, constitutional rights and due process, as students seek clarification about these and other events they have seen in the news and on social media.

“Being teenagers, they mouth off on occasion. They were very worried that if they were in a situation like that, and they said something, that they would be arrested, detained, searched,” Clark said. “It’s a lot of stress to put on 14-year-olds.”

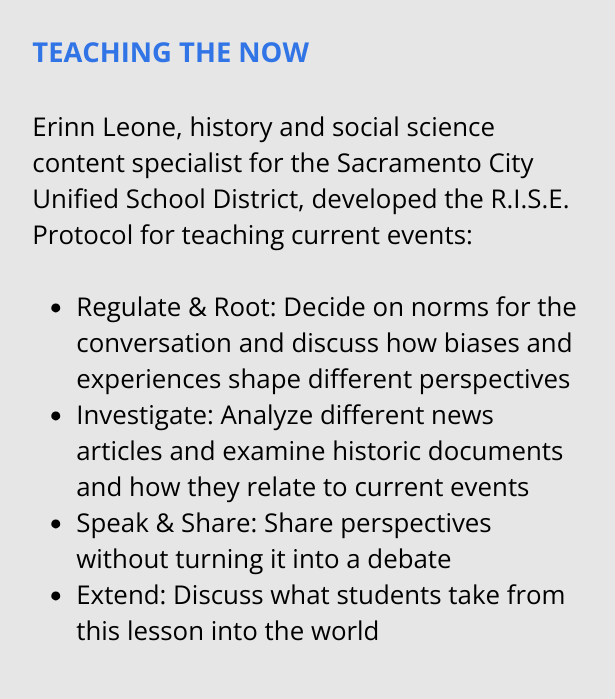

Erinn Leone, history and social science content specialist for the Sacramento City Unified School District, said teaching about current events can help students learn important skills they will need as adults, such as analyzing news articles, understanding biases and being able to discuss issues with other people who disagree with them or have different perspectives.

“It’s important for making the history we’re learning in the classroom relevant, so they see that things happening today are rooted in historical context and things don’t happen out of the blue,” said Leone, who recently conducted a training about teaching current events called “Teaching the Now.”

In addition, she said, it’s important for students to have a space to process what they see on the news and social media.

“Current events impact our students. They cause fear in our students. It’s important for us to not ignore what’s happening in their everyday lives,” Leone said. “When we don’t bring those things into the classroom, it’s noticed.”

“There’s some anger, there’s shock”

Los Angeles Unified School District teacher Manuel Gochez said the students in his Advanced Placement Government class had a lot of opinions about the disparities they saw between the videos of the shootings of Good and Pretti and the way the Trump administration described the shootings.

“There’s some anger, there’s shock, there’s disappointment, too, in the way people are being treated and the inhumanity of it all,” he said.

Gochez and other teachers said students had questions about whether federal immigration agents were following the law, which led to discussions about what happens when law enforcement does not follow the law and the checks and balances of the three branches of government — judicial, legislative and executive.

“The students are usually the ones asking the questions and leading the conversations,” Gochez said. “My job, more than anything, is to give a space to discuss. They have a lot of thoughts and opinions, and if they don’t feel safe in the classroom or in school, it can be a lot they’re holding in.”

After the Jan. 21 publication of an internal ICE memo stating agents had the right to enter homes without a judicial warrant, students in Gabriel Perez’s ethnic studies classes in Fresno Unified asked, “Can ICE come into our house now?”

“I’ve had students cry in front of their classmates. You see the stress, you see the fear, because many of their parents are undocumented. It’s something I see all the time,” Perez said.

First Amendment discussions

Some English teachers are also bringing current events into their classrooms.

“I think it’s extremely important to connect what’s happening now with what’s happening in our literature. I always tell students that if you really want to know what was happening at the time, read a book,” said Benny Martinez, who teaches English in South Central L.A.

His 10th grade students have just finished reading “Fahrenheit 451,” the 1953 novel by Ray Bradbury, in which, under a fictional future government, all books are banned and “firemen” burn them. Martinez said the book sparked discussion among his students about recent efforts to ban books about LGBTQ issues or race from some school libraries.

“We were talking about First Amendment rights and freedom of speech being taken away,” Martinez said. “The students were asking, ‘Why are we banning books?’ It’s important to understand other points of view.”

Next, Martinez’s students will read “Night,” Elie Wiesel’s memoir about surviving the Nazi concentration camps. In preparation, Martinez has been teaching his students about the Holocaust.

“A lot of them are interested in that topic because of the idea that history could repeat itself,” he said.

Clark said in her district, Pajaro Valley Unified, in Santa Cruz County, ninth graders don’t take social studies, so she incorporates units on the Constitution and the history of labor unions into her English classes. This year, she also taught a unit on the history of deportations in the U.S.

Students brainstormed questions for the class to research, including “What percentage of people deported have had criminal records? What percentage have been here longer than 10 years?”

Clark said the vast majority of her students are U.S. citizens, but estimated that about 25% to 30% have undocumented relatives.

“They are very worried. We all heard during the campaign that the administration was going to focus on criminal undocumented immigrants, and that’s just not what’s been happening,” said Clark, referring to Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign.

Setting boundaries and guidelines

Some teachers shy away from conversations about current events in class because they are afraid of complaints from parents or administrators. Heather Miller, who teaches “Women and Gender in Ethnic Studies” in Fresno Unified, said there is a lot of concern, especially since some ethnic studies teachers have been accused of antisemitism after discussing the war in Gaza or the relationship between Israel and Palestine.

“What can we say? What can’t we say?” Miller said. “There’s a lot of fear around losing our jobs or getting complaints.”

Still, Miller said students bring up current events even if teachers don’t. “In my AP classes, I’m teaching imperialism right now,” she said. “What do you say when they say, ‘Oh, are we imperializing Greenland now?’ ”

Leone, the history and social science specialist, recommends that teachers and students agree on guidelines for these conversations beforehand to make sure they are respectful, including acknowledging different perspectives and criticizing sources, not people. She also recommends that teachers take time to discuss how different people’s experiences and identities shape their perspectives.

As a teacher in South Sacramento, Leone facilitated discussions in her class about police shootings. Some students had loved ones who had negative experiences with law enforcement, while others had fathers or uncles who were police.

“We’re teaching students to think about different perspectives and engage with people who have different perspectives,” she said. “It’s important that I’m not teaching students what to think, I’m not teaching them what to believe. Every student is entitled to their own belief. But they’re also required to think critically about those things and ground their discussion in facts and truth.”

Los Angeles Unified teacher Gochez said these conversations can also be an opportunity to teach students about civic participation.

“It’s an opportunity to empower them,” he said. “If you don’t like what’s occurring, you have a voice; you can do something about it.”