In summary

Just one bill invests in bilingual education programs and its focus on instructional materials is a far cry from the systemic change advocates have called for.

As California gets closer to its 2030 goal of having 1,600 dual language immersion programs in the state’s public schools and advocates call for a more ambitious vision, legislators have pumped the brakes on funding.

In 2021, the Legislature created a $10 million grant program to help schools expand dual language programs over the last three years, but now that money is gone. The only bill before the Legislature this session would have the state spend just half that over the next three years, with that $5 million going to buy or create books and other teaching materials in languages other than English.

Conor Williams, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation and an education policy expert, is a critic of California’s limited investment in dual language immersion programs, which have students spend part of their school day learning in English and part of the day learning in another language. He said the new grant program “feels a little bit like replacing the windshield wipers when you’ve got a flat tire — or two flat tires. You can fix them but you’re not going anywhere until you address the tires.”

Dual language immersion programs have become sought after by parents of all backgrounds wanting their children to become bilingual. In the 2023-24 school year, 1,075 schools had students enrolled in such programs, according to data from the California Department of Education, which puts the state on track to meet its 2030 goal. The education department especially encourages schools to offer these programs to the children of immigrants because research shows they help students learn English better and faster, close academic achievement gaps and lead to a host of beneficial long-term outcomes.

Advocates like Williams want many more children from this group to have access to bilingual education. Yet data obtained from the Education Department show only 10% of English learners were in some type of bilingual program during the 2023-24 school year.

To get a meaningful portion of these children a bilingual education, the state needs many more teachers. Yet no bills this session aim to address the bilingual teacher shortage.

“This is almost like gas in the tank,” Williams said, continuing with his analogy. “You just can’t do what everybody in California says they want to do in California until you fix the teacher pathway problem.”

Slow progress, tight finances

Global California 2030 projected the state would have 90 approved bilingual teacher preparation programs by 2025. Yet according to the state commission on teacher credentialing, there are only 48.

As CalMatters reported in December, the state’s anemic bilingual education offerings are a direct result of a ban on such programs from 1998 to 2016 and the state’s failure to create a systemic recovery since then.

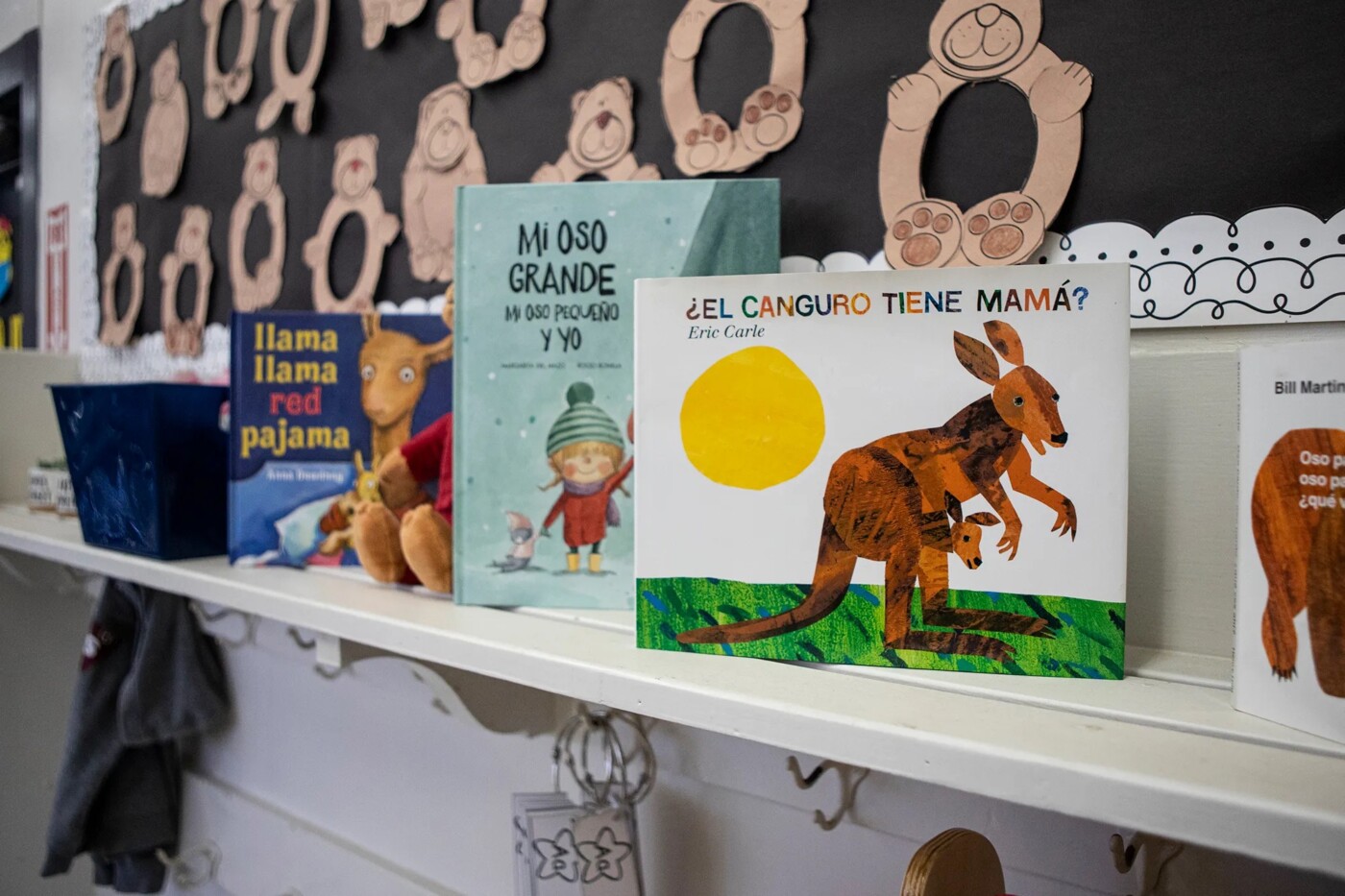

Recognizing the state’s tight finances this budget year, advocates did not push for any major initiatives. But Asians Advancing Justice worked with Assemblymember Mark González, a Los Angeles Democrat, to introduce Assembly Bill 865, which calls for $5 million over the next three years to help schools either purchase or create instructional materials for bilingual programs. Outside of English and Spanish, it is difficult to find high-quality, standards-aligned materials, and the funding is expected to take the pressure off teachers to create their own.

Martha Hernández is executive director of Californians Together, a coalition that includes Asians Advancing Justice and which formed to oppose and overturn the state’s 1998 ban on bilingual education.

“There’s much more that we need to do related to the expansion of biliteracy programs, such as addressing the teacher shortage,” Hernández said. But the instructional materials grant program is “one critical piece of the puzzle,” she added. She expects the grant program to improve equity across California schools and help close achievement gaps between students who speak less common languages and their English-speaking peers.

Assemblymember González sees the grant as a lifeline for districts developing critical programs. “We need to learn other languages,” he said. “It’s crucial to the success of the future of California.”

González represents one of the most linguistically diverse legislative districts in the state and said educators describe having to create their own standards-aligned instructional materials in less common languages like Korean and Armenian. That’s time teachers can’t spend designing engaging lessons or giving students helpful feedback.

Seeking more funding

Hernández said she is still hopeful the state will put more money behind bilingual education programs before the budget year wraps up. Assembly Bill 2074, signed into law in the fall, called for a formal implementation plan for the state’s English Learner Roadmap, which outlines how schools can best serve students who do not speak English fluently. There are more than 1.1 million of these students in the state’s public schools, or about 1 in 5 students statewide. After AB 2074 passed without any funds attached, a budget trailer bill set aside money for one new position at the California Department of Education to spearhead this work.

Hernández said the department has also been pursuing philanthropic funding for an advisory committee established by the law that would create a more concrete plan for implementing the roadmap and develop a way to hold districts accountable for achieving that.

But Californians Together would like to see more money for the effort. The original bill called for three new staffers at the education department, not one, so the coalition will continue to advocate for the original request. And once the state’s finances are in better shape, the coalition has a lot more to ask.

“This is a step,” Hernández said. “But we are working on a campaign for a multiliteracy education for all. This is a very long vision.”

In the meantime, Williams has been writing about how Texas does a better job of educating students still learning English. His latest report points out that California and Texas each have about the same number of students who enter school speaking a language other than English. But in Texas, these children outperform their Golden State peers on a national test of reading and math in both fourth and eighth grade. The state also has significantly smaller gaps in performance between English learners and those who already speak English fluently.

While many factors affect test scores, making it impossible to say for sure that bilingual education causes Texas students to outperform Californians, Williams said the consistent gap at both grade levels every testing year is compelling: “It’s just another confirmation point to say that the persistent investment in Texas is getting better results than the pretty modest investment in California.”