When Calvin Brown saw his young son’s first seizure, all he could do was stand back, helpless. He recalls growing angry at the paramedics who didn’t seem to be doing much, either.

Now, dozens of seizures later, Brown knows it’s best to just let them run their course. But on that day a decade ago, watching his son writhe in the grass and foam at the mouth, Brown only had a gnawing feeling that no one was there to help.

“It was scary,” Brown said. “It hurt my heart because I didn’t know what to do.” A few years later, when doctors ran tests on then-11-year-old Elijah, they found the amount of lead in his blood was more than seven times the level the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers as elevated. It’s an extreme but not uncommon occurrence in Oakland, especially for families from East Oakland like the Browns.

In high concentrations, lead causes these kinds of urgent problems, like seizures and muscle weakness. But the constant exposure to lead in small doses can be even more devastating. Over a lifetime, several U.S. agencies have suggested that exposure to the toxic metal can lead to cancer. But inside kids, it can also stunt their learning and development.

A small increase in blood-lead concentration can result in a decrease in IQ by as much as two points, experts say. And multiple studies over the last decade have shown a link between lead levels and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

In some of Oakland’s neighborhoods, lead levels are among the highest in the state. Early in the 2010s, the rate of tests showing elevated lead levels in the blood of some West and East Oakland children was above 6%. That’s higher than in Flint, Michigan, during its high-profile water contamination in 2014.

But about five years after Elijah’s first seizure, Oakland got an unprecedented opportunity to do something about its lead problem. In 2019, the city, alongside nine other jurisdictions, won hundreds of millions in a settlement with paint companies who produced lead-laced paint. Oakland walked away with more than $14 million to address one of the nation’s most acute lead crises.

In the years since, other cities and counties have put those funds to work. Alameda County, which received a separate share of funds, has put them toward providing emergency care to more children with elevated blood levels.

Almost immediately after the settlement, Los Angeles County launched a service to repair lead-ridden residences and maintained the program through the COVID-19 pandemic. Los Angeles County hopes to repair its 1,000th unit by the end of the year, according to Janet Scully, who heads the county’s program.

But Oakland has lagged behind. It hasn’t spent a single penny of its settlement spoils, a public records request revealed. Its first chunk of funds is slated toward paying consultants later this month to develop a plan to spend the rest. And according to internal documents, the city doesn’t expect the consultants to even present their plan until the fall of 2025.

“It hurt my heart because I didn’t know what to do.”

Calvin Brown, Oakland father whose son suffers seizures from lead poisoning

Then, last month, the lead contamination bubbled up through school faucets and into the public consciousness. Oakland Unified School District announced that it had found lead coming out of more than 80% of water fixtures at its schools, sparking outrage among parents at a contentious school board meeting last week.

There, OUSD admitted that it failed to alert community members for an average of some 60 days after it first found out. Now, the OUSD findings have sent local officials scrambling to see if they can divert Oakland’s settlement funds to schools for emergency repairs.

As the city stares down a lead crisis, Oakland has been hampered by both bad timing and mishaps of its own making. In trying to tackle its lead problem, Oakland for years lost track of funds from the lawsuit, lost staff working on the issue and rebuffed partnerships with other settlement recipients. And Oakland’s inability to implement its funding from the 2019 settlement has baffled those working on lead prevention in the state.

“Lead poisoning is one of those public health crises that is completely preventable,” Scully said. “If we’re not facing it with a sense of urgency, then we’re potentially putting young children at harm.”

THE $500,000 QUESTION

When the settlement money arrived in 2019, it came in an almost $24 million check to Alameda County. Oakland and the county were supposed to figure out a way to divide it. Those negotiations took the better part of two years before Oakland finally received its $14 million cut in 2022.

“With this rare opportunity with the Lead Paint settlement resources, the City must thoughtfully design a sustainable program that will support the needs all of the Oaklanders who reside in the highest lead burdened census tracks in the County of Alameda,” Oakland spokesperson Sean Maher said.

But the $14 million that Oakland received in the 2019 settlement is not the only pool of money from the lead paint lawsuit that it has failed to find a plan for.

In 2011, Millennium Lab Holdings, parent of one of the paint companies in the lawsuit, found itself struggling after the financial crisis. Facing bankruptcy proceedings, Millennium settled early with the 10 California jurisdictions.

It wasn’t a lot. Oakland got $539,000. Scully said Los Angeles County got around $750,000. But the money was enough for Los Angeles County to run a pilot program to strip lead paint from 10 houses in 2018-19.

Scully describes this initial program as “really successful,” both as proof of concept and as practice to work out the kinks in her overall lead operation. That way, when the larger settlement came in 2019, that county already had a proven plan for its Board of Supervisors to sign off on.

Then there’s Oakland, which lost track of that $539,000 for most of the 2010s. The city promised to use its “best efforts to ensure that all funds…are used to abate the public health hazard caused by lead paint” in a signed agreement with the other nine jurisdictions. Then, it received its check for $539,000 in June 2011. And, in its financial statements for the year, Oakland acknowledged that it had received a settlement for about that much.

But that money still wasn’t added to Oakland’s budget for almost another decade.

Larry Brooks, who directed lead prevention services for Alameda County until last month, said he first noticed that Oakland hadn’t accounted for the funds in its budget around when he arrived at the county’s Healthy Homes Department in 2013. His department is countywide and receives federal funding, and he said it runs most of the lead abatement efforts in Oakland. For years, he said, Oakland gave shifting or confusing answers to his inquiries about its settlement money.

“Right now, I have federal dollars that I’m using to do lead abatement throughout the county. And a lot of that money, I’m spending on lead abatement in Oakland,” Brooks remembers telling Oakland staffers. “It kind of feels unfair that we’re spending these federal dollars in Oakland when Oakland has settlement money that they could be utilizing.”

Around this time, Oakland officials seemed oblivious to the Millennium settlement. During the first half of 2017, the city’s Community and Economic Development Committee held a series of meetings, trying to begin a lead abatement pilot like Los Angeles. And at the first meeting, Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan said she had a recollection of Oakland receiving money in some settlement but added that she had no idea where it went.

However, nobody at that meeting brought up the Millennium $539,000 in response to Kaplan’s inquiry, including Brooks. And the settlement dollars never came up again during the others, even as staff projected their proposed pilot to cost about $500,000 for its first year.

Oakland did not respond to a series of questions about the status of the Millennium settlement, either currently or from 2011-2021.

As Brooks kept pestering the city for answers, some councilmembers launched internal inquiries into the money, he said. Then, Oakland finally added the Millennium settlement to its budget under the 2020-21 fiscal year, almost a decade after it first received it.

When it did add the money, Oakland stashed it in its general fund. It’s the most flexible pot of cash the city has. A smattering of services receive their funding from it, so it is unclear to Brooks if Oakland spent that money, or if it plans to. Or if the city still knows it exists at all.

In fact, any mention of the $539,000 is noticeably absent from several recent documents outlining Oakland’s plans for lead abatement.

“That is the $500,000 question: what happened to it?” Brooks said.

‘WE COULD NOT DO THIS ALONE’

Brown has learned to deal with the lead. He has learned the anxiety of waiting for Elijah’s blood test results, unsure how much lead was still inhabiting his body. He learned to feed his son peanut butter, which several state health departments say helps to draw lead out of people’s bodies. Learned to pat Elijah’s arm and speak softly to him until his limbs go limp and the seizure subsides.

At their worst, Brown said, Elijah would suffer a half dozen seizures a day.

“He cramps. He turns his head sideways. He shakes,” Brown said. “He might fall down if he’s standing up, and he just jumps around for a minute.”

For how much Elijah’s lead poisoning has shaped their lives for the last decade, Calvin Brown isn’t too sure how it began. That’s because lead is seemingly everywhere in Oakland. Eighty percent of census tracts in Oakland are above the state’s median for lead exposure.

Lead can sometimes appear in Oakland’s soil. In the spring and summer, 70 water fixtures at Oakland schools spat out concentrations of lead higher than state or federal standards allow, an OUSD report found.

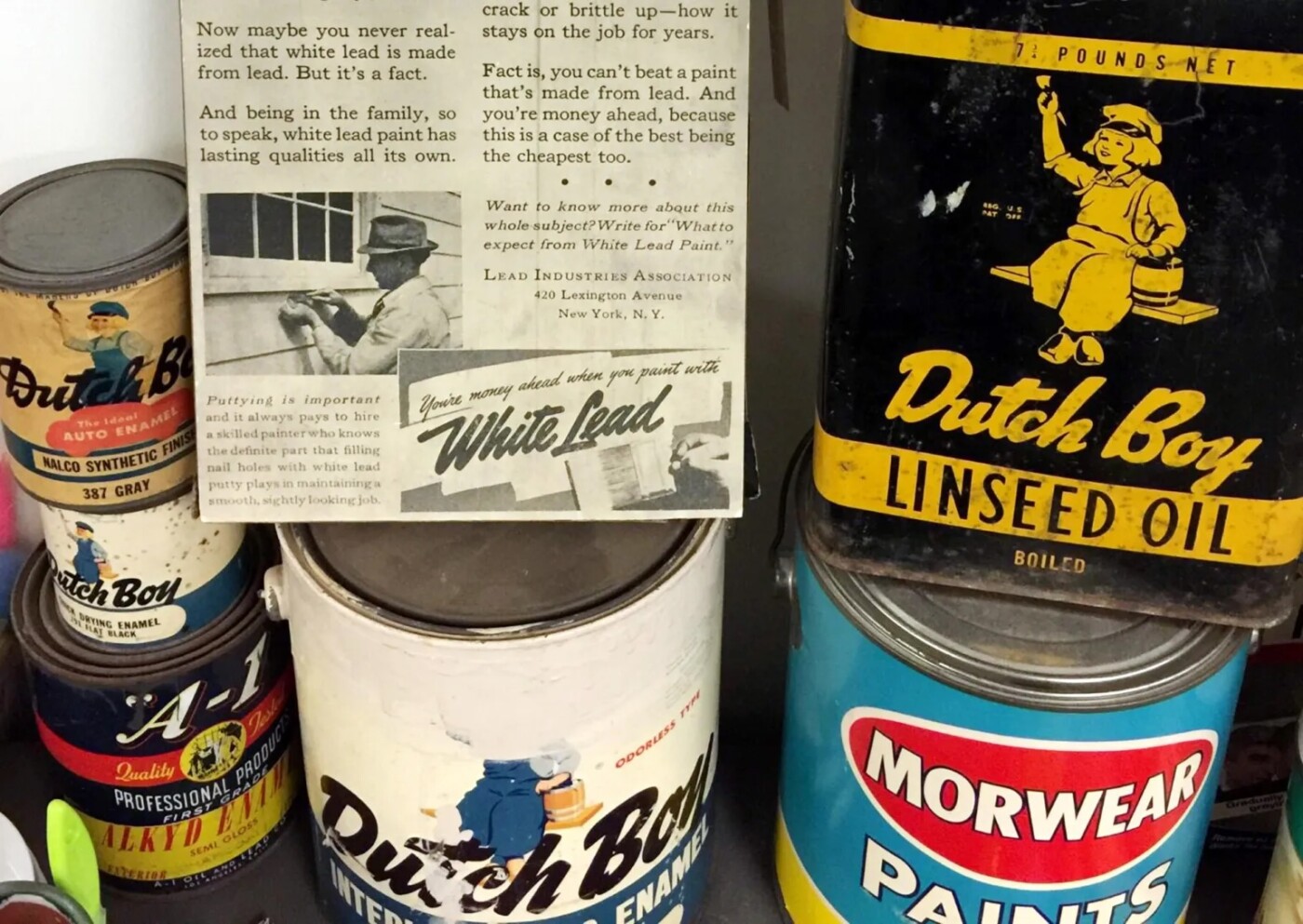

But perhaps Oakland’s most significant source of lead is its houses. As the country rapidly built housing during the 20th century, paint companies, like those which settled with Oakland, made paint with lead to produce supposed brighter hues and quicker drying. But as its harmful side effects came to light, the federal government banned lead paint in 1978.

By then, tens of thousands of homes had been built in Oakland, many of them likely slathered with lead-based paint. A lot of that has likely been sealed beneath subsequent layers of more paint. But the lead still lurks beneath those newer coatings, waiting for high-friction surfaces like doors or windows to grind it down to a dust that can be inhaled.

It’s a difficult task to address the sheer number of old homes. Fixing a lead hazard sometimes means temporarily relocating the unit’s tenants until it can be sealed with a new coat of paint or stripped to its wooden frame completely. Los Angeles County spends $35,000 to fix each house before relocation costs, according to Scully.

Oakland’s ambitions, though, seem to match its problems. As recently as June, Oakland was looking to launch an inspection program where rental units would be periodically tested for lead, similarly to how restaurants are inspected for food safety. This strategy is held up as the gold standard among experts. Rochester, New York, used it to cut the number of kids with lead poisoning in its surrounding county by 80% in the decade after the program went into effect.

But Oakland currently leans on Alameda County to provide lead testing and other services in the city. And some California lead prevention experts, like Brooks, worry that Oakland might be biting off more than it can chew.

“Oakland doesn’t have the people with the expertise in child lead poisoning prevention, and understandably so,” Brooks said, pointing to the squadron of nurses, inspectors and lead experts Alameda County already employs. His department, Brooks said, also has a rolodex of relationships with local contractors that do lead abatement, built in the more than 30 years since its founding.

That kind of built-in infrastructure is necessary to get money spent, said Scully, who oversees the Los Angeles County funds. She admits that she didn’t know too much about lead abatement when the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health tapped her to implement its funds.

But as the settlement negotiations entered their final stages, Scully partnered with the Los Angeles County Development Authority, which specializes in home rehabilitation.

Scully’s program is less comprehensive than Oakland’s vision for inspections (though Los Angeles County will soon launch an inspection program with a separate pot of money). Scully’s department, in contrast, fields reports of lead-ridden houses and then repairs them. The Development Authority had the contractor connections she needed to get those repairs underway.

When the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health announced their money from the 2019 settlement, it announced them as a joint venture between the two agencies.

“Very early on, Public Health knew that we could not do this alone,” Scully said.

Oakland, though, has taken an opposite approach to Brooks, his Healthy Homes Department and other government entities offering help.

‘WE STAND READY TO HELP YOU’

As the amount of lead in Elijah’s blood stayed high after his first seizure, Brown noticed that his arms and legs were moving more slowly than normal. Before then, Elijah had been a runner, playing in the family’s backyard regularly. With lead poisoning, Elijah barely had reflexes anymore, Brown said.

In the years after his lead poisoning, Elijah lagged behind his peers too, his father said. The elder Brown wants officials to give the same urgency to lead as they do to crime, to drugs and to other issues that grab more headlines but have similar scale of consequences.

More than 800 Oakland kids showed up to hospitals with elevated levels of lead in their blood in the six years leading up to the 2019 settlement, and many more have likely suffered the effects of lead without even knowing it.

“We’ve got enough problems out here with drugs, everything else going out here,” Brown said. “Lead will poison your mind just as bad as drugs do.”

When the settlement was finalized in 2019, Brooks was skeptical that Oakland had enough infrastructure in place to give the money the urgency he thought it deserved. Instead, Brooks proposed skipping negotiations between Oakland and Alameda County. He offered to instead take Oakland’s share of the settlement but would promise to only use it for programs in the city, he said.

However, around that time Oakland commissioned a Race and Equity Impact Analysis on lead, which was released in 2021, and wanted to fund its recommendations. The report ended up being a good one, Brooks said, and Alameda County has even incorporated some of its findings into its work elsewhere.

Brooks still worried that Oakland lacked the experience to implement the recommendations from the report, but it “forced his hand,” he said.

Oakland rebuffed his offer to take over its programming, he said, and headed to negotiations.

Brooks remembers those negotiations as a bit nasty, at times. The Race and Equity analysis criticized Alameda County for not testing enough children. Alameda County would ramp up testing if it had the money to do it, Brooks remembers shooting back.

Then, in 2021, both sides struck a deal. Oakland would get $14.1 million, $4.8 million immediately and then the rest once it showed the county it had a program up and running. In spring of 2022, the county transferred the first payment and then turned to its own work. Oakland was determined to go it alone.

“We’ve got enough problems out here with drugs, everything else going out here. Lead will poison your mind just as bad as drugs do.”

Calvin Brown

In a statement, Oakland said that it is still considering partnerships with Alameda County and that it will rely on its consultants to evaluate the county’s programs.

“It just seems like right now, they want to remain as distant from the county as possible,” Brooks said.

But soon after it got its check from Alameda County, Oakland was rocked by its own staffing turbulence. The city lost two Housing and Community Development directors, as well as some staff. Oakland also transitioned a fellow working on lead prevention and the attorney advising staff on it, according to internal documents.

These departures, according to the documents, ground internal meetings to a halt from 2022 into 2023. It wasn’t until “the stabilization of department staffing” that the group was able to resume action on the settlement funds, an internal workflow document says.

Brooks remembers having trouble making contact with Oakland staff during this time. And when he finally did a year ago, it was mostly new faces that needed him to catch them up to speed, Brooks said.

He has even dusted off his offer to assist Oakland’s efforts for the fresh ears.

“I’ve talked with some Oakland staff, even this week about ‘we stand ready to help you,’” Brooks said in August.

Brooks doubts Oakland will say yes; for years, it has seemed disinterested in collaboration to both to Scully and himself.

The jurisdictions that received money from the 2019 settlement gather regularly to discuss their respective programs and the lessons they’ve learned along the way. Some of the smaller cities are still in the infancy of their programs, and Scully said they use those meetings to lean on the more-established programs for advice.

When those smaller jurisdictions needed a contract for construction, for example, Scully said she was happy give them Los Angeles County’s version as a template.

“I shared with the others, so they’re not reinventing the wheel,” she said.

All 10 jurisdictions attended when the meetings began in 2016, Scully and Brooks said. But after the 2019 settlement arrived, Oakland has been conspicuously absent from the meetings, Brooks and Scully say, even as they’ve personally inquired about why representatives weren’t coming anymore.

In a statement, Oakland said it strongly denies declining to participate in calls with the other jurisdictions. Oakland said its staff actually asked to participate in these meetings.

But Brooks pushed back on Oakland’s claim. He invited the city to the statewide meetings, a September 2023 email to Oakland staffers shows. But, in the half-dozen or so meetings since, Oakland’s been nowhere to be found, he said.

“Alameda County participates,” Scully said. “But Oakland hasn’t been at the table.” If they were in better contact, they might have learned that Los Angeles County had discovered that jurisdictions could earn interest on their settlement funds, which Scully said came as news to some of the other counties.

Los Angeles County has earned an extra $2 million this way, according to Scully. It is unclear if Oakland earns interest on the money it holds, but Brooks and Alameda County are holding most of Oakland’s money, per the 2021 agreement. Brooks said it’s not his money to touch, so it’s been sitting in an account that doesn’t earn any interest.

“That money is sitting there while children are being exposed to lead, and we cannot use it,” Brooks said, audibly frustrated.

Financially, it still could have been even worse for Oakland. The California jurisdictions decided to settle with the paint company in 2019, but they could have won more in a judgment. However, the court would have expected the cities to spend their winnings within four years, or it would go back to the paint companies instead.

“Like all of Oakland’s money would’ve gone back at this point,” Scully said.

It perplexes her why Oakland has been hesitant to accept help, especially from Alameda County.

I’m not totally clear on the relationship between Alameda County and Oakland,” Scully said. “I really think that if they could work in partnership, that would kind of be the best-case scenario.”

‘YOU’VE GOT TO WORK AT IT’

It has been about a decade since Calvin Brown stared at his son seizing in the grass, furious that no one seemed to be interested in helping Elijah. Still, a similar feeling eats at him.

Brown said he’s worried that Oakland has mismanaged the funds from the settlements and blown an opportunity to make life a little easier for East Oakland parents like him. He can’t understand why Oakland officials haven’t just started small, with anything. One school, one block, he suggested, then move on.

“You’ve got to work at it,” he said. “How in the hell do you expect people to give you more money if you’re not showing no effort that you are doing something with the money you’ve got?”

Perhaps part of Oakland’s sluggish progress is, ultimately, due to the scale of its problem and its ambition. In June, Oakland staff estimated that an inspection program would cost $20 million per year, quickly exhausting its money from the settlement. The city would first need to find a way to sustain the inspections, the staff memo said, before it considers starting them.

“The City is grateful to have these funds and is aware that based on the number of units impacted by lead paint the $14.1 million isn’t enough to address all of the needs of the community,” said Maher, the city spokesperson.

Scully has come to a different calculation, albeit with a less comprehensive program. Los Angeles County has about 800,000 homes that might qualify for repair, she said, but the settlement revenue is only enough to cover 3,000 of them at best. Still, Scully said having a program up and running makes it easier to apply for federal grants to sustain the work beyond when the settlement funds run dry.

Brooks’ Healthy Homes Department is funded through an annual fee levied on properties in four cities within the county, which has sustained the department since the 1990s. As long as the fee exists, so too does Healthy Homes in some form. It can maintain some abatement services after the settlement dollars are gone, part of Brooks’ reasoning to offer help to Oakland.

But Brooks’ offer has a bit of a time limit. He said he is set to retire in February after some 12 years of prodding Oakland to get an inspection program off the ground. Almost certainly, he’ll retire before one comes to fruition.

“I was pretty much raised in Oakland,” Brooks said. “I think that’s part of the reason why I have such a passion for wanting them to have a rental inspection program.”

Brown hasn’t connected with any of the hundreds of Oakland parents who have seen their children afflicted with lead poisoning. It’s enough work caring for his own. Most of his time, Brown said, is spent shepherding his son to school or trying to get his lead levels down.

He bought his son a goat last year, and it’s gotten Elijah back outside and playing again. The peanut butter sandwiches seem to be working, too. Brown said that Elijah’s blood-lead level spikes every now and again, but it’s been coming down steadily for years now. And the seizures have slowed too, he said.

Still, Elijah’s blood-lead level is still considered elevated, Brown said, which means more peanut butter, more anxiety after blood tests and more times being the one who helps his son.

“I’m not stopping until it gets to zero,” Brown said.

The post Leaded legacy: Oakland has received millions to clean up its lead, so why hasn’t it spent it? appeared first on Local News Matters.