Of course Jeff Bleich remembers the day he met Willie Mays. The then-head of the San Francisco Bar Association was invited to watch a San Francisco Giants game by Martha Whetstone, who was executive director of the Association at the time. The tickets were in Mays’s suite.

“We walk in and Willie’s there. I was completely tongue-tied,” Bleich said. “When he got up to go to the bathroom, she said, ‘What’s wrong with you? I told him you were fun. You’ve met a president.’”

Bleich said he said something to the effect of, “Anybody can be president, anybody can be center fielder for the Giants, but there’s only one Willie Mays.”

“Pick up your game, you’re embarrassing me,” Whetstone replied.

This was the beginning of a long friendship that lasted until Mays died last month at the age of 93. Bleich served as the executor of Mays’s estate. He also worked with Mays in the Say Hey! Foundation, which Mays created to serve underprivileged youth through sports as well as education, nutrition and providing safer communities from San Francisco to New York.

At that first game Bleich watched from the suite, he opened up enough that Mays asked him for some help with an issue he had with American Airlines. Mays had been given a lifetime pass to fly on the airline years before, but now the airline wanted out of the deal, according to Bleich. Mays asked Bleich to join him in Dallas to clear things up at the corporate offices. Bleich said that on the trip, Mays turned on the charm and the issue was resolved.

That was the first of many trips together. “We traveled all over the country together,” Bleich said. “We went to the Hall of Fame ceremony in Cooperstown together. He was thinking of doing a movie, we flew out to Georgia together. We went to the White House together when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.”

Out here in California, together they would go to Cache Creek and Jack in the Box. In a video interview with Mays several years ago, Mays talked about Bleich, “He’s a really honest man. If he doesn’t know something, he’ll tell you right away, ‘Let me find out.’ [Jeff will] get right back to you. He’s a magnificent man.”

Bleich said that he thinks their friendship went beyond baseball. “I liked baseball but I think part of the reason he liked me was that I wasn’t obsessed with it,” he said.

However, there were lots of baseball stories. “He said in center field he could see everything that was going on,” Bleich said. “He spent a lot of time observing tendencies of hitters and pitchers. He spent a lot of time directing traffic. Before they had computers they had Willie’s brain.”

Mays started his professional career in 1948 at 17 years old when he played for Birmingham, AL in the old Negro Leagues. Major League Baseball had just integrated the year before when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Mays played just 13 games before the New York Giants signed him and sent him to Minneapolis. In recent years, Negro League statistics were added to the Major League records. Ten hits Mays got with Black Barons are now part of his official record.

“He told a great story about how when he was starting out, it was the first time he traveled into places with a white team, staying in the white hotels and he wasn’t allowed,” Bleich said. “He was staying in the rough part of town. He was a 17-year old kid. He was probably scared. He heard a knock on his window, and it was his teammates. They had him open the window and they came in and slept on the floor so he wasn’t alone.”

Bleich said Mays treated segregation as something to be overcome with his play. If Mays played for your favorite team and you didn’t like Black people, well, that forced you to confront racism without him having to say a word.

Mays died on June 18, just a couple of days before the Giants faced the Cardinals in a special regular season game at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field, the same park where Mays got his start. He had already announced he wouldn’t be able to make the trip, but he asked Bleich to make a statement for him at the game. The city was dedicating a mural of Mays as part of the event. Mays had also sent the city the gift of an antique clock.

“Birmingham, I wish I could be with you all today,” Mays wrote. “This is where I’m from. I had my first pro hit here at Rickwood as a Black Baron. And now I hear that all these years later — that hit finally got counted in the record books. Some things take time. But I always think, better late than never. Time changes things. Time heals wounds. And that is a good thing. I had some of the best times of my life in Birmingham. So I want you to have this clock to remember those times with me, and to remember all the other players who were lucky enough to play here.”

Bleich told the crowd, “Willie looked forward to this day. He was honored when he heard about this mural, because he loved Birmingham: it is more than where he grew up or learned to play ball; the people of Birmingham were his first team.

“What we put up on our walls says a lot about what you value. Willie was very moved by this mural, because it reflects what Willie meant to this City. Willie felt the same way about Birmingham. Willie earned a lot of awards in life. But among them, on the wall in his office, he hung his high school diploma from Fairfield Industrial High School, and the key to the city of Birmingham.

“He never forgot where he was from. And he was always on Team Birmingham.”

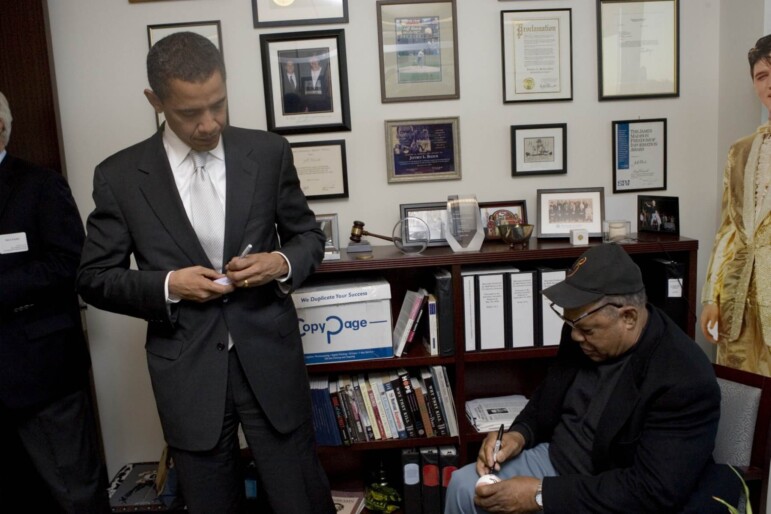

Mays was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2015. Bleich had introduced the two several years prior. “I was hosting a book signing for then-Senator Obama at my building in 2006,” Bleich said. “Willie was interested in meeting Barack, but didn’t want to upstage him, so we met in my office before the event started. The two of them were star struck and shyly asked for each other’s autographs. Barack signed his book, and Willie signed a ball that Barack wouldn’t put down. After Senator Obama left, Willie said, ‘That guy is a cool cat. I’ve met some presidents and he could be President.’”

Obama spoke via a recorded message at a Day of Remembrance for Mays at Oracle Park on July 8. Bleich spoke in person, telling the crowd, “Sometimes we think people are great because they were great ballplayers. Willie Mays was a great ballplayer because he was a great man.”

Photos courtesy of Jeff Bleich