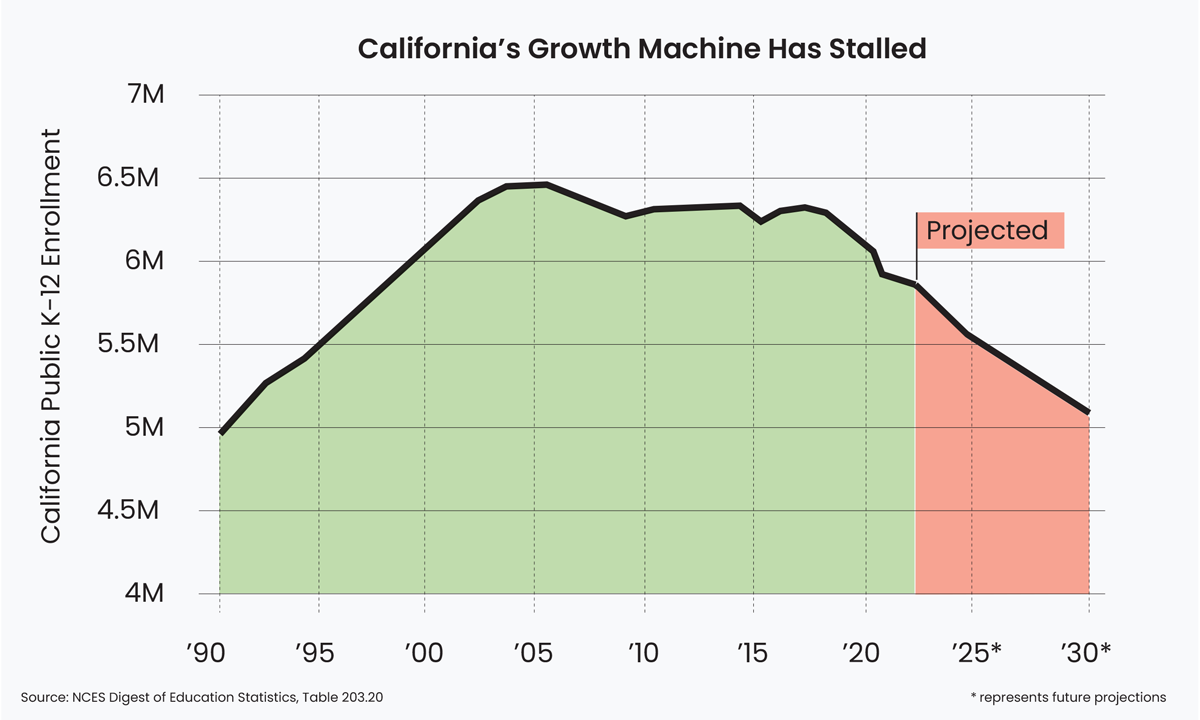

California public school enrollment passed the 5 million mark in 1991. That number quickly grew to 6 million by 1999 and then reached 6.4 million students in 2004.

Then, the growth machine stalled. California has long seen a large percentage of its residents move to other states, but international immigration and high birth rates more than made up for those losses. That formula is no longer working, and this year researcher Hans Johnson found that the number of births per 1,000 California residents was at its lowest level in more than a century.

Within education, the declines were small at first. But then COVID-19 hit, and the state lost 420,000 public school students in four years. California’s pandemic-era enrollment declines were not just the largest numerically, the 6.7% drop was also the second-largest in percentage terms.

There’s potentially more bad news in store for California school districts. According to the latest forecast from the federal government, the state is projected to lose another 1 million public school students by 2031.

If a private-sector business has fewer customers, its revenue will decline proportionally. Public education revenues are broadly linked to enrollment, but the relationship is not as linear.

There are three main sources of revenue for public schools — local, state and federal. Local funds, which in California make up about one-third of school district revenues, come from property taxes and are not directly tied to student enrollments. Federal formula funds are linked to how many students a district serves, as well as how many of them are low-income or receive special education services. But aid from Washington is so diffuse and such a small part of district budgets that it’s not enough to move the needle, at least in the short run.

That leaves state funds as the primary area where serving fewer students will affect a district’s budget. Theoretically, state policymakers could decide to spend the same amount of money even if schools enroll fewer kids. That could actually raise per-pupil revenues in districts, but only if they are all losing students equally.

But enrollment declines have not been universal across or within states. In California, two-thirds of districts suffered an enrollment decline during the pandemic, but that means one-third actually gained students. The biggest loser, in numeric terms, was Los Angeles, which lost 67,000 students (14%) over four years. Other notable losers include Long Beach (down 10%), San Jose (down 15%) and Cupertino (down 22%).

Where the rubber will really hit the road is in schools with declining enrollments situated within districts that are shrinking overall. Most districts allocate money to schools according to staffing ratios, so a school would get less staff if it served fewer students.

It turns out that California has a lot of schools with large enrollment declines. When The 74’s Linda Jacobson worked with Brookings Institution researchers to run the numbers, they found over 1,400 schools in California that had suffered at least a 20% enrollment decline. Those were particularly concentrated along the Pacific coast, and they are the ones most at risk.

It simply costs more per pupil for districts to offer the same level of services at schools that are partially empty. And, as Marguerite Roza and Ash Dhamani cautioned recently in a piece for EdSource, this has consequences for the entire district. When districts try to prop up too many underenrolled schools, they eventually have to cut back on “music, electives, AP courses, athletics and other supports” across all their schools.

To put it in concrete terms, the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University has compiled school-level spending information for every state and district, and it lets users sort schools across a variety of categories. When I narrowed the search to California elementary schools, almost all the highest-cost schools were small, and likely underenrolled. Meanwhile, almost all of the biggest schools fell below the statewide average in per-pupil spending.

California school districts received $18 billion in one-time federal relief funds, and that money has allowed districts to operate beyond their means temporarily. But the money expires at the end of September, and then leaders will have to make some painful decisions to more closely align their budgets with the number of students they serve.

The views expressed here are those of the author.