In summary

Die-offs from algae blooms in San Francisco and Delta water diversions have left a giant, shark-like, prehistoric creature at risk. State wildlife officials approved white sturgeon as a candidate for listing, which triggers protection.

Killed by algae blooms and dwindling from dams and droughts, the largest freshwater fish in North America is at risk in California. Today, wildlife officials took the first major step toward protecting it under the state’s Endangered Species Act.

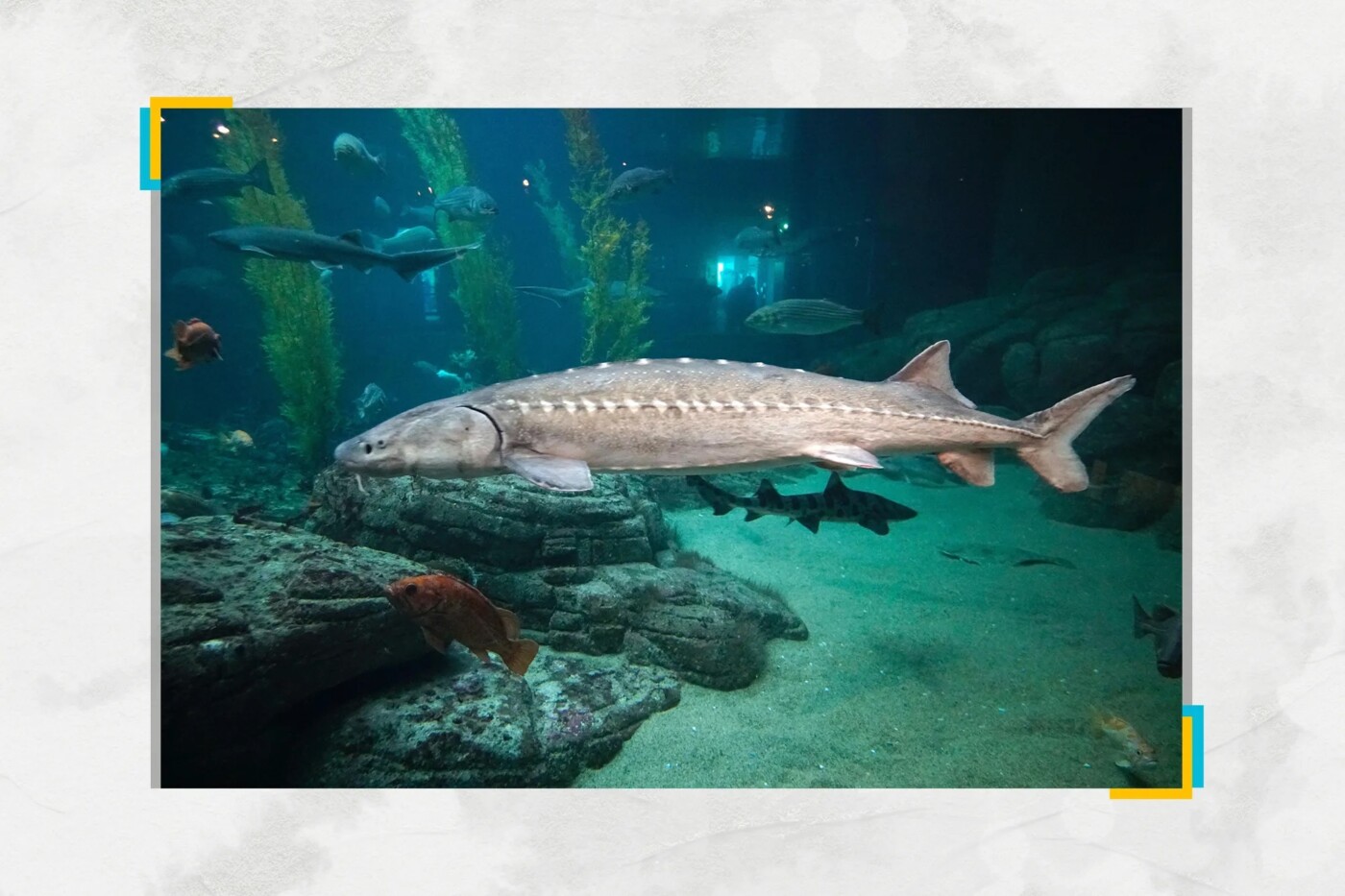

White sturgeon, which can live longer than 100 years, historically reached more than 20 feet long and weighing almost a ton. Facing an array of threats, this shark-like, bottom-feeding fish with rows of bony plates, whisker-like sensors and no teeth has declined — and their numbers will likely continue to drop.

California’s Fish and Game Commission unanimously approved white sturgeon as a candidate for listing, which launches a review by the Department of Fish and Wildlife to evaluate whether it is in enough danger to warrant being declared threatened or endangered. The review is expected to take at least a year.

In the meantime, the fish will be protected under the California Endangered Species Act until the commission makes a final decision whether to list it as threatened or endangered. Harming or “taking” a species with any kind of project — such as water diversions — or activity such as fishing is “prohibited for candidate species the same as if it was fully listed,” said Steve Gonzalez, a spokesperson for the fish and wildlife agency. Permits and exemptions, however, can be granted in certain situations, he said.

Today’s decision comes in response to a petition filed by a coalition of environmental groups and the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance for the species to be listed. They await a verdict on a federal petition, as well.

“This is an ancient lineage … they’ve withstood everything that Mother Nature had to throw at them, which makes it particularly poignant that they’re having trouble surviving us,” Jon Rosenfield, science director of San Francisco Baykeeper, one of the four groups that led the petition, told commissioners today.

California’s wild white sturgeon migrate between San Francisco Bay and the rivers of the Central Valley, largely the Sacramento River. They successfully reproduce only every six to seven years — typically during wetter years when more water flows out of the Delta.

Back-to-back algal blooms in the San Francisco and San Pablo bays killed large numbers of sturgeon during the past two summers. Nearly 870 carcasses were recovered in the summer of 2022, and at least 15 last summer. Experts believe thousands more likely died and sank to the bottom of the bays.

Overfishing for sturgeon eggs — caviar — and smoked fish drove the species to near-extirpation in California by the turn of the 20th century. For more than 100 years, commercial fishing of white sturgeon has been banned.

California’s emergency rules for the recreational fishery, adopted in 2023, already reduced the maximum size limit of harvested fish from 5 feet to 4 feet, and cut the annual catch total from three fish to one.

Now the sturgeon’s temporary status as a candidate for listing will ban recreational fishing, unless the commission later grants an exemption sought by fishing groups.

Without an exemption, the decision “has the potential to cause irreparable damage (to) the business and recreational anglers who fish for White Sturgeon in California’s coastal, Delta, and inland waters,” fishing groups wrote in a letter in early June. “Recreational angling is not the cause of concern to the health of this fishery. Instead, this fishery is suffering from the mismanagement of our precious and limited water supplies.”

Many aquaculturists who farm domesticated sturgeon for caviar and meat raised concerns at the meeting, and commissioners reassured them that the regulation would not affect them. Indoor-farmed white sturgeon are included on lists of fish that experts consider sustainable and recommend for consumption.

Environmental groups said that without more protection, the fish will become even more imperiled as climate change squeezes water supplies, fishing continues and major projects planned for the region, such as the Delta tunnel, deplete more freshwater flows.

The die-offs during the past two summers “exacerbated…an already unsustainable level of fishery exploitation of White Sturgeon into a crisis situation,” wildlife staff wrote in a report for the Fish and Game commissioners. “In order to protect the surviving population of White Sturgeon and maintain a recreational fishery into the future, immediate steps were necessary.”

Sturgeon ancestors date back to the Cretaceous Period more than 120 million years ago, making them the most prehistoric and primitive of all bony fish. Instead of teeth, they have a long snout like a vacuum cleaner used to scrounge for bottom-dwelling shellfish, worms and mall fish to swallow whole. Today the largest ones grow to 10 feet and 400 pounds.

The rivers of the Central Valley, primarily the Sacramento River system, are among the few places where white sturgeon reproduce in the wild. Others include the Fraser River in British Columbia and the lower Columbia River in Oregon and Washington.

Their numbers in California are dropping, plummeting from a historical abundance of 200,000 harvestable fish to a recent five-year average of about 33,000, according to the Fish and Wildlife department.

The threats are many: Over the centuries, the Sacramento and San Joaquin River watersheds and San Francisco Bay have been fundamentally replumbed. Now water diversions for farms, cities and hydropower sap flows and dams limit migration. Pumping kills fish; introduced predators eat the young. Contaminants taint the waterways and poachers illegally harvest wild fish for their eggs.

A coalition representing water users in the Delta contested data pointing to long-term declines but commissioners dismissed that concern.

The Department of Water Resources, which operates the major water project funneling water south from Northern California rivers, will now need to apply to the state wildlife agency for a “take” permit for operations and fish screens at pumping facilities.

“We’ve already begun that process in anticipation of the candidacy being reached today,” said Lenny Grimaldo, environmental director of the State Water Project. He said the project takes “takes relatively low numbers of white sturgeon in any given year.”

State officials working on the proposed Delta tunnel project also are evaluating impacts to white sturgeon and plan to investigate how sturgeon respond to fish screens and river flows, Grimaldo said.

Before today, white sturgeon were considered a “species of special concern” — meaning it had no protection but that continued population or habitat declines could qualify it as threatened or endangered. Green sturgeon, California’s other sturgeon species, are already listed as threatened under federal law.

Chris Schutes, executive director of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, one of the organizations that signed the petition, said it was a difficult decision to call for more protection.

He said California’s sport and commercial fishing industries are already reeling from the cancellation of salmon fishing for the second year in a row. Losing the ability to fish for white sturgeon adds to the burden.

“Many party boat skippers feel it’s going to affect them — that people won’t want to fish, if there’s not some chance that they can take a fish home,” Schutes said.

Still, he added, the goal is to get ahead of population declines before it’s too late to reverse them.

“Sometimes, I think we only see crises in retrospect, when we should have seen them sooner. And I think that we’re at that point — and it’s time to do something.”