Bay Area writer and art historian Bridget Quinn is back with a rare, historical banquet brimming with rich and juicy stories about women artists.

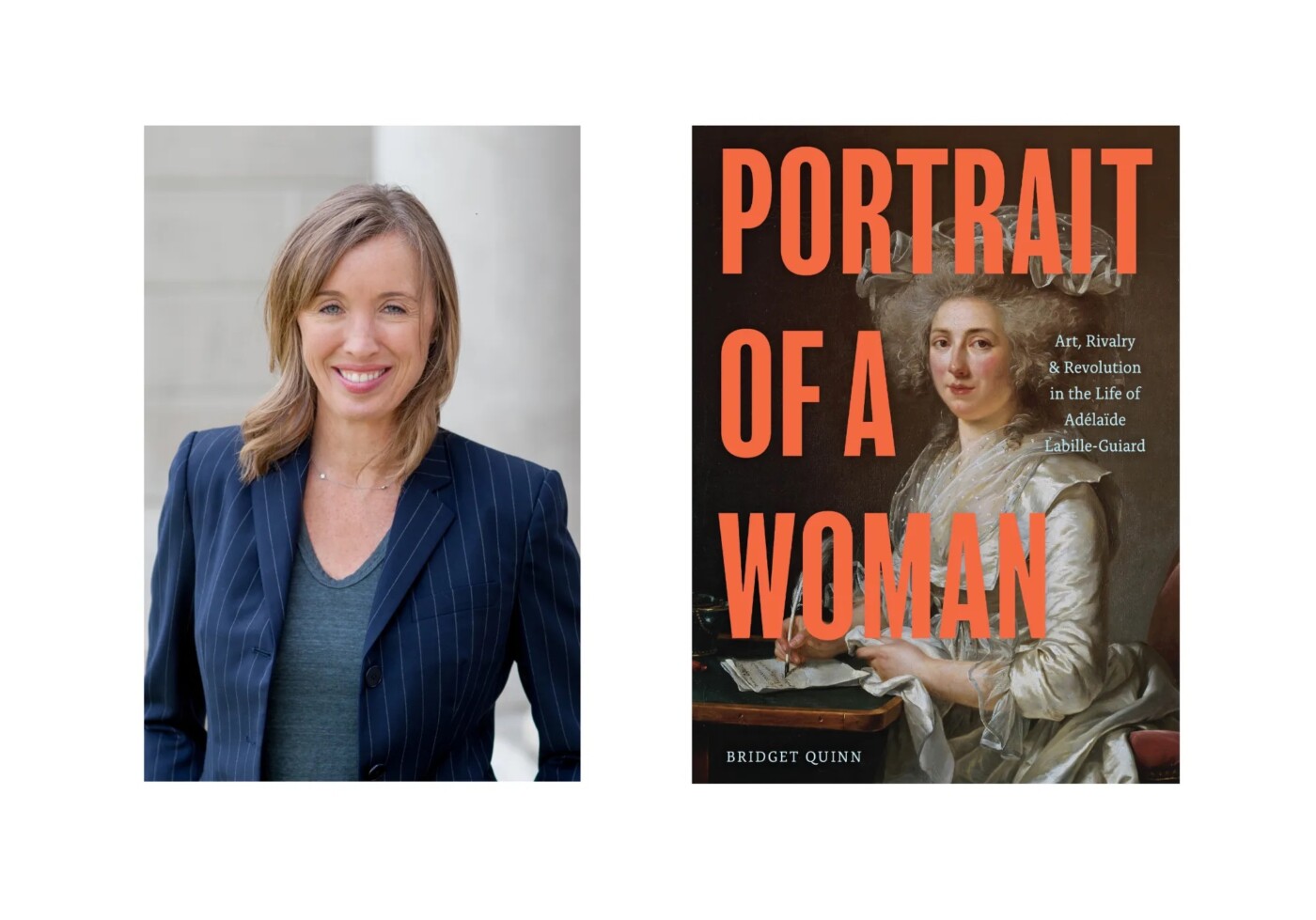

Quinn, whose book “She Votes” documented women’s suffrage United States, is in her element again with “Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry and Revolution in the Life of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.” (Chronicle Books, 184 pages, $29.95).

The book, which she’ll launch on April 16 at Book Passage in Corte Madera, is a journey through her life-changing fascination—some might say obsession—with obscure 18th century French artist Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.

A trailblazer and advocate for women, Labille-Guiard’s paintings hang in some of the most famous museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. But she’s been an obscure figure in art, and Quinn’s biography of her is a first.

“One of the greatest rivalries in art“

Quinn spent decades researching Labille-Guiard and the manufactured rivalry between her and the wildly popular Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun, another French artist in Paris during the late 1700s. By today’s standards, the spark was set innocently enough: When a savvy art promoter looking to make a splash displays their work side-by-side, he launches what Quinn describes as “one of the greatest rivalries in art.”

Admittedly, the world loves a cat fight. But Quinn calls out the rivalry for what it was: a lot of spin that fed a common trope that still exists today.

“You can think of it as Beyonce versus Taylor Swift,” Quinn says. “There’s this idea in Western art history that there can only be one exceptional woman at any given time.”

Creative writing

Quinn layers vignettes from Vigée-LeBrun’s indulgent memoir with what little we know about Labille-Guiard. Then Quinn does something magical and daring: She imagines what Labille-Guiard might have thought and felt during the ups and downs of her artistic and personal life. At one moment, Quinn is sharing stories from the art history canon, and in the next, she’s spinning yarns that come from three decades of walking in another person’s shoes.

“I have been a little bit haunted by her,” Quinn says of Labille-Guiard. “I encountered her at 22 and I finished this book at age 54. I tried to imagine what was happening to her and what her life was like.”

Quinn admits this creative approach caused her some trepidation. She was anxious about “the art history police” coming for her, she says. But much of history is a story that someone else decided on, she says.

“I am at least showing my hand,” she says.

Indeed, the artworld was extremely stingy with praise and acknowledgement of women artists of the day. As Quinn’s story unfolds, she follows Labille-Guiard and Vigée-LeBrun to the doors of the prestigious Académie Royale, the institution that set the tone for French art and admitted as few women as possible.

Suddenly, a twist of fate puts the Académie Royale within reach for both artists. Controversy! Two women joining the mostly male Académie on the same day? Quinn delves into the drama of the era with writing that’s full of tension and color. What will become of these two women pitted against each other?

The challenges Labille-Guiard and Vigée-LeBrun face in the male-dominated art world are cringe-worthy.

And there’s the inconvenient truth for woman in 18th century France: marriage. For all their differences in personality, demeanor and life ambition, Adélaïde and Élisabeth both succumbed to this societal demand. Anchored in marriages that were not in their best interest, they managed to advance their careers, mostly painting royalty.

Surviving the guillotine… and history

By the time Labille-Guiard and Vigée-LeBrun arrive at the gates of the French Revolution in the late 1780s, Quinn’s storytelling takes on a nail-biting quality. This was an era of opposing factions and fervor, of the people rebelling against royalty, of guillotines falling on necks with zero due process.

Vigée-LeBrun—a royalist and Marie Antoinette’s favorite portraitist—wisely leaves Paris for Italy. And Labille-Guiard—a moderate ally of the revolution—stays in France but moves away from the volatile center.

When Quinn writes about the Revolution—a terrifying and complicated time—at least a few Americans will feel a chill of familiarity.

“Someday, maybe soon, the extremes of revolution would burn themselves out, leaving a democratic middle,” she writes. “One where women and men alike, from every estate, could live and thrive.”

But things get worse. Labille-Guiard suffers a horrific injustice that she never truly recovers from at the hands of revolutionaries shaping the new republic. A few years later, the Revolution replaces the Académie Royale with the Institut de France and closes its doors to women.

The ever-popular and buoyant Vigée-LeBrun contributes to Labille-Guiard’s obscurity by outliving her and never mentioning her name in her best-selling memoirs.

But that can’t be the end of the story. And thanks to Quinn’s connection to Labille-Guiard and her fearless embrace of fact and historic interpretation, it isn’t.

“This is why women’s stories are erased—because we so often don’t have the same kinds of information about them,” Quinn says. “But men have so much written about them, in their own time and after. And if that’s the only yardstick we can use to examine the past, that means women and people of color will continue to be marginalized in history.”

There’s a payoff for readers when Quinn channels a historic figure like Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. She gives readers permission to let their imaginations run wild. And that’s when history becomes more than just a book, but a delicious journey that is feels close, real and current.