In 1938, Gawen Brownrigg, 27, the sports editor for East Africa’s largest newspaper, went to bed in the hotel room he rented in Nairobi in British-controlled Kenya. He was alone that night, unlike the other evenings he spent with ex-pats enjoying drinks and the privileges that came with being white in a Black country colonized by England.

Brownrigg had come to Kenya eight months earlier to escape his troubles. He was a British baronet whose American wife had left him, taking their infant son to California. His novel “Star Against Star” about the love between two women had not made the splash he hoped. A recent engagement to a woman he met in Kenya had been called off.

Gawen went to bed that night. He never woke up.

The official inquest determined that Gawen had killed himself. The report cited as proof an empty bottle of barbiturates found in a trash can. It was a finding that Gawen’s mother Beatrice never accepted, and she spent the rest of her life insisting he had died of a bad heart.

Sylvia Brownrigg, an accomplished writer in Berkeley, didn’t know any of these details growing up. In fact, her father Nick, who was divorced from Brownrigg’s mother, rarely discussed his British family. He was more focused on his new life living off the grid in Ukiah with his second wife. Brownrigg didn’t meet her paternal grandmother, who lived in New Mexico, until she was 21.

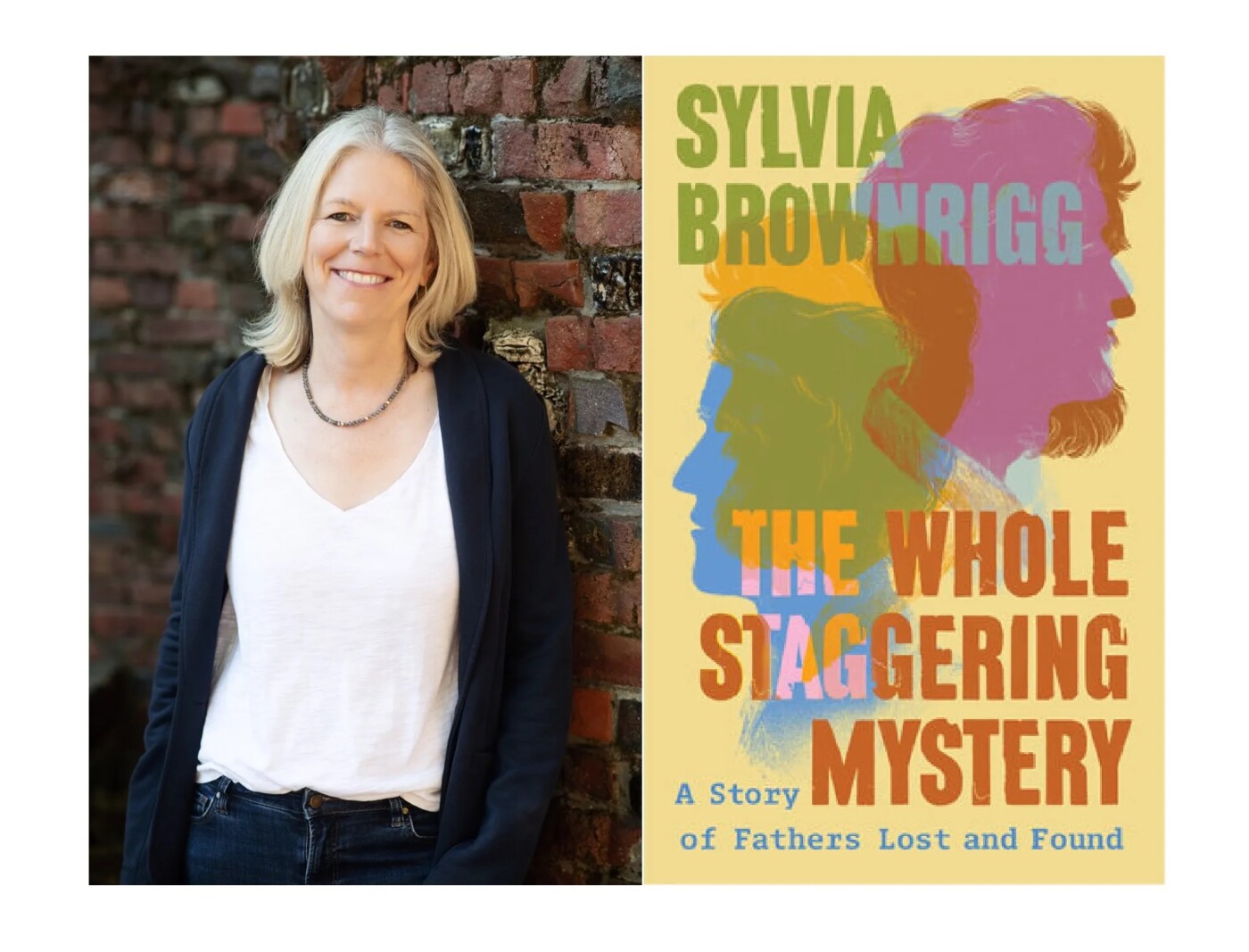

Why does a family keep secrets? What does it mean to lose a father at a young age? Why erase one’s past? Those are some of the questions Brownrigg poses and tries to answer in her new book, “The Whole Staggering Mystery: A Story of Fathers Lost and Found” (Counterpoint, $28, 336 pages) released on April 23. “Not knowing your son or your father is a yawning emptiness in life,” Brownrigg writes.

Brownrigg is best known for her novels, including “Morality Tale,” “The Delivery Room” and “Pages for You” and “Kepler’s Dream,” a book for middle school readers that was turned into a feature film.

Both fiction and nonfiction, “The Whole Staggering Mystery” explores the lives of Gawen Brownrigg and Nick, the son he barely knew. Also examining Sylvia’s relationship to her unpredictable and absent father, it takes readers from well-appointed drawing rooms in England to colonial Kenya to Los Altos in the days before it was part of Silicon Valley and to the redwood forests of northern California.

“What I love about ‘Staggering Mystery’ is the unexpected way Sylvia uses fiction in a nonfiction medium—though memoir is more subjective and impressionistic than much nonfiction—the way the book bursts into fiction like a musical bursts into song. That is incredibly deft, and I think helped meet the challenge of filling in blanks in her family history and becomes a commentary on how we all tell and understand our family stories, especially as we get older and the ones we wish we could have asked are gone,“ said Berkeley writer Peggy Orenstein.

Kirkus called “Staggering Mystery” an “immersive reading experience,” and gave the book a starred review.

Brownrigg’s role in the story started in 2012 when she received a bundle that had been left in her aunt’s house in Los Angeles for 50 years. The note indicated that the bundle was meant for her father Nick. But he had no interest in examining the package’s contents, even though it contained a bulging scrapbook his grandmother Beatrice Brownrigg had made for him about his father.

It wasn’t until Nick died that Brownrigg and her brother closely examined the scrapbook. It contained multitudes that explained Gawen Brownrigg’s life, including letters he wrote to his young son, correspondence from publishers, photos and more. After reading it, “I joined the long queue of people who could only wish Gawen had lived many more years,” Sylvia says.

Local News Matters posed questions about “The Whole Staggering Mystery” to Brownrigg, who will discuss it with Orenstein at 7 p.m. Wednesday at Mrs. Dalloway’s Books in Berkeley. The conversation has been lightly edited.

How did opening the long-lost package containing information about your grandfather change your sense of self and of your family history?

The most vivid moment of discovery for me, after we opened the package, was finding the letter that my grandfather wrote home to his parents after his little son, my father Nick, was born. It was such a sweet new-father note about the birth, his nervousness, his comical surprise that his wife really seemed to love the baby. I read it aloud to my dad, who was fading mentally at the time but still listened carefully. I was in tears as I read it.

This letter showed that my grandfather Gawen Brownrigg was an affectionate and funny person. It made my grandfather seem likesomeone I would be happy to claim and feel some connection to.

The biggest revelation could have been the argument that my grandfather had not, after all, died by suicide; his mother was convinced that his heart simply stopped in the night, as he had always had a weak heart. A death by suicide leaves a certain mark, and maybe we had been wrong to believe in that.

But the central fact for me was learning that the English family my father had come from was a loving and warm one, who had wanted above all to stay connected to their little American grandson. To me, as a mother, as a daughter, that is one of the most heartbreaking things in the story: that my dad was cheated of knowing this about his own father. Unfortunately, Nick’s mother, Gawen’s ex-wife, did all she could to turn her son away from any positive stories about or memories of Gawen. It was selfish and unkind of her.

Why do you think your father wasn’t interested in looking at the package’s contents, or talking to you about his British roots, including that he was a baronet?

My dad’s mother went on to marry three other times. She had already remarried when Gawen died. So my father had three potential stepfathers, though only one, the father of his two half-brothers, was in place for any length of time. Then as a teenager, he was sent away to boarding school.

I believe because of the times, and my grandmother’s willful badmouthing about Gawen after his death, Nick was encouraged to forget about not only Gawen, but all his English family. I think his mother encouraged him to shut the door on that side of his background. He might have developed curiosity about them as an adult; but if he did, it wasn’t something he shared with anyone, certainly not my brother and me. When we were growing up, we did not see our dad often; he was estranged from his mother, who was still alive; and he told us literally nothing about his own background. He was, to use a current expression, a person who lived very much in the present. Living on and taking care of this wild piece of land, with his second wife, took up all his time and attention. He didn’t look back.

The book explores the impact of absent fathers. You reckon with your father, Nick, who divorced your mother when you were young and lived off the grid in the woods in Ukiah for much of his life. He wrote, but never published, and for a long time you regarded that as a failing. How did exploring his life, and that of his absent father, change your perception of him?

When I started writing this book, I had gotten used to considering my dad from a conventional point of view: What had he achieved? What kind of parent had he been? In those terms, my dad was not a “success.” For years he had wanted to be a writer, but never managed to publish a book; he had never held a steady job, a fact made possible by his mother’s financial support; and he had frankly been an unattentive and not-present parent when we were young. He was involved in his own life and did not seem to care much about ours. When I got into Yale, he was genuinely shocked! He did not attend my graduation or other important events.

Throughout writing the book, and assessing my father’s life differently after I absorbed how much he had been deprived of family connections that could have made a real difference to him—I mean emotionally, not practically, though perhaps it would have been both—I came to see the richness of the life he made for himself with his wife Valerie, and feel less judgmental about it. In our adult years, our dad was better able to express his affection for my brother and me and our families. He wrote wonderful letters to me throughout my life: funny, observant, vivid letters that were, in the end, the place where he poured his literary talents and imagination. He was a generous host. He was funny, hardworking, smart, irreverent—and, against the odds (as he himself might have pointed out) had a lot of love in him for his family. He was surprised he made it to 60; and amazed that he made it to 80. He once wrote to me he felt like a big baby, so lucky to have his kids and grandkids around him. I think his self-awareness was a quality he had that I admired, deeply. He took the long view. He was, in his way, philosophical, and I have discovered I have more of him in me than I’d ever have guessed.

The book blends memoir and fiction to tell the story of your father Nick, your relationship with him, and the story of your grandfather, who died as a young man in Kenya, far from his home in England. Why did you take this blended approach? What did adding fiction to the mix allow you to do that straight nonfiction would not?

I knew that writing sections of this book in stories, fictional pieces, would be a formal risk, but I also came to see that writing short stories was the only way I’d be able to get closer to the emotional truths about both my father, a man I knew, and Gawen, a man I never could know. (He died in 1938.) With my dad, it was only through writing fiction that I was able to tell freely some stories from the early years on his ranch, when he was drinking heavily but also when we were learning a lot about that wild place. I did not want to be tied down to precise details about how the hunting expedition went, or the night we got stuck on the muddy access road in the truck, and he had to winch us out. (Though I did read up a lot about winches so I could describe that scene!) My imagination has always been more able to vividly create scenes through fictional retellings, so that was the best way I could bring the Circle C, and my father’s character, to life. I was also able to imagine my way into his perceptions of my brother and me, and that I think got me to some important truths.

With my grandfather, writing about life in Nairobi and the impact of his death on the people he loved, helped me to convey the sadness of that loss, as well as some of the texture of his Kenyan life, which I absorbed through reading his letters home, and talking to people who grew up in British colonial Kenya in that era. I found the essayistic tone I had first tried to use became kind of stilted; it was only when I turned to short stories that I could bring my grandfather to life.

The simplest way to put it is that though writing a memoir and sketches of my family life growing up has been a powerful and interesting new literary adventure, I am at heart a writer of fiction, and it is through stories that I often find my way to expressing my understanding, feelings, and perceptions.

Sylvia Brownrigg appears at 7 p.m. April 24 at Mrs. Dalloway’s, 2904 College Ave., Berkeley. The event is free; registration at mrsdalloways.com/events is requested.