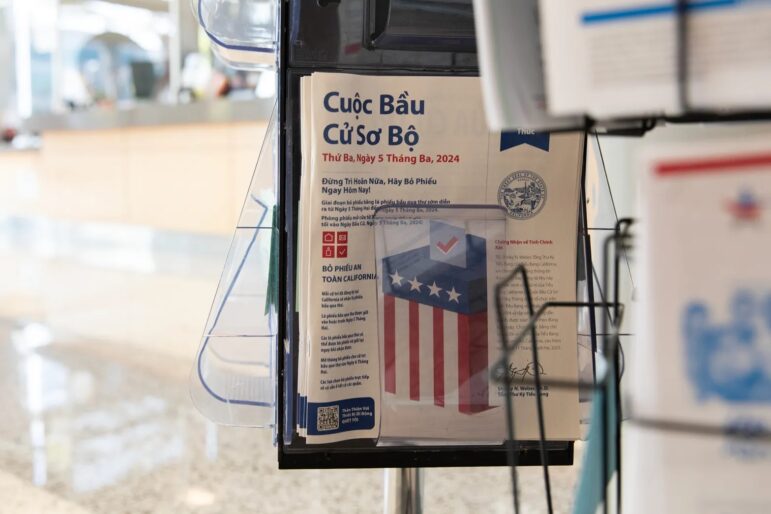

California lawmakers are considering a bill that would expand language assistance and election services to immigrants who don’t speak English fluently, but a group representing voter registrars throughout the state says it will cost counties too much money.

California has the nation’s highest proportion of households that speak languages other than English. Nearly 3 million voting age Californians have limited English knowledge.

Assemblymember Evan Low, the Cupertino Democrat who co-authored Assembly Bill 884, said he hopes it will increase voter participation and strengthen democracy in California.

“California is one of the most diverse states and leads the nation in language diversity,” he said, “so it is important that we lead the way to providing in-language ballots and voting materials to reduce barriers and enfranchise more Californians.”

The bill, which passed the Assembly in late January and is before the Senate, would require California’s Secretary of State to identify the languages spoken by at least 5,000 voting-age individuals in a county who don’t speak English fluently, including groups not covered by current federal voting rights laws, such as Middle Eastern or African immigrants.

The Secretary of State would then have to provide language assistance, including a toll-free hotline and funding for county language coordinators, in areas where the need is most acute.

If the proposal succeeds, it would require San Diego County, for instance, to translate voting material into Somali and at least 20 other languages, the bill’s sponsors say.

“We want voters to trust the government and that boils down to a voter in any community being able to understand what is happening in their own community,” said Pedro Hernandez, a policy director at California Common Cause, which cosponsored the bill.

If it is successful, the bill would go into effect in 2025, too late for next Tuesday’s primary and the November general election.

Immigrant voting rights

Federal and state laws are meant to ensure all eligible voters can vote, regardless of English proficiency. However many foreign-born American citizens face significant language barriers when casting their ballot.

Under current state law, there’s no requirement to provide voter information guides or translated materials about voter registration in languages not covered by the federal Voting Rights Act, which passed in 1965 but was expanded in 1975.

Now federal law requires counties to provide election material to population groups which meet specific size thresholds. Groups must comprise more than 10,000 voting-age citizens or 5% of all voting-age citizens in a county. That has led to translated materials for those who speak Spanish or an Asian, Native American or Alaskan language.

California has lower population thresholds, requiring translations of sample ballots for greater numbers of eligible voters, but not other services such as votable ballots in other languages or poll workers who speak other languages, advocates said. Thousands of immigrants still lack equal access to the polls, advocates said, because they rely on languages not covered under federal laws.

Under state law, in each year with an election for governor the Secretary of State must determine the voting precincts where 3% or more of the voting age population is citizens in “language minority” groups who can’t vote without English language assistance.

The Secretary of State relies on census data to make language coverage determinations. But the Census Bureau provides limited data on small populations, claiming privacy protections, advocacy groups said.

In 2022, when California Secretary of State Shirley Weber initially decided to reduce the number of languages required to be translated from 27 to 10 in some precincts, her press secretary, Joe Kocurek, attributed it to the reduced Census data.

Days later, after CalMatters published a story on the issue, Weber reversed her decision. She told CalMatters at the time: “This drastic change was extremely troubling both to me and to the counties who provide services to these voters, because reduced language assistance has the potential to disenfranchise voters who may not receive voting materials in the appropriate language.”

Overlooked voters

For Safiyo Jama, passing the American citizenship test meant she can play a role in a democratic system she has long admired. In 2012, when Jama voted in her first U.S. election, other African immigrants in the San Diego area asked her to provide translations and voting assistance.

“They wanted to know what this candidate would do; they wanted to know which candidate was best for all of us,” said Jama, a 40-year-old Somali immigrant. “If there were ballots in Somali, more people would vote.”

Thousands of Somali refugees like Jama immigrated to San Diego County in the 1990s, as civil war ravaged the East African nation. Decades later at least 1,400 voting-age Somali residents in the county have self-identified as having limited English proficiency, though voting rights advocates say that’s likely an undercount.

A recent report by voter advocates says the federal government’s definition of “ language minorities” overlooks many voters who speak African or Middle Eastern languages.

For instance, there are 659 precincts in Los Angeles County containing Arabic speakers, but only 123 meet the state’s threshold for providing translated materials and services. Because Arabic is not covered under federal law, election offices are not mandated to provide election services in Arabic, the report said.

In contrast, Korean voters in neighboring Santa Barbara County, which has 12 precincts covered for translated voting material in Korean, receive language support because the voters with limited English proficiency live in highly concentrated population areas, the report said.

The system therefore benefits communities that are residentially segregated, advocates said.

That could change under the proposal. For instance the bill would mandate San Diego County provide translated voting material in Arabic.

According to the San Diego Registrar of Voters, the county already translates sample ballots into Arabic, as well as Japanese, Korean, Laotian, Somali, Persian and other languages. Officials would not answer questions about the bill.

Advocates said translated sample ballots are useful, but they still pose difficulties for eligible voters who don’t speak English well. The lack of assistance in their specific language and having to rely on friends, family, even children to provide translation are the main reasons these eligible voters don’t register in the first place, advocates said.

Fiscal concerns

Though the bill passed in the Assembly, it triggered financial concerns as lawmakers face a projected multi-billion-dollar budget deficit.

An Assembly Appropriations Committee analysis said the bill’s implementation would initially cost $28.8 million in fiscal 2024-25 and annually about $15.2 million, including language identification and translation duties, voter outreach, upgrades to phone systems and a voter registration database.

The Secretary of State’s office did not respond to CalMatters’ questions about the proposal’s potential costs.

A statewide group representing county registrars and election officials, the California Association of Clerks and Election Officials, said it supports the goal of providing voters with election materials in their preferred language, but it opposes this bill due to financial concerns, said Bob Page, its legislative committee co-chair.

“For many counties that currently have more state-covered languages than federal-covered languages, increasing language service requirements could be expected to more than double the county’s language service costs and demand on labor,” the association wrote in a letter to Assemblymember Chris Holden, the Pasadena Democrat who chairs the Assembly Appropriations Committee.

Today eligible voters can register to vote online and by mail. California requires all counties to mail voters a ballot ahead of an election. Voters can return them by mail or drop them off at a ballot box or voting center, or they can vote in person.

In precincts where the 3% language threshold is met, a county must provide translated sample ballots and translated instructions to voters. But some advocates said that’s not enough.

“You can’t use a sample ballot to vote on,” said Deanna Kitamura, senior staff attorney at Asian Americans Advancing Justice, a bill co-sponsor. “You’re holding up the sample ballot in your language and then you’re having to look at it and mark the English ballot, which you use to vote on.”

Building trust

Kitamura testified in November to an Assembly committee that a 2015 study found language assistance increased Latino voter registration by 15% and expanded voter turnout by 15% in Asian American communities. When San Diego County started providing language assistance, voter registrations rose by more than 20% among Filipino Americans and by almost 40% among Vietnamese Americans, Kitamura said.

Other states have expanded assistance to voters whose languages aren’t covered under federal law. Oregon and Minnesota, for example, provide online voter registration in Somali. California does not.

“In order for California to build trust, it has to be a multiracial and multilingual democracy, which means prioritizing and centering in language access,” said Hernandez at Common Cause.

Common Cause was one of a dozen organizations that participated in the California Language Access Workgroup launched in 2021. As part of its agenda, the Partnership for the Advancement of New Americans, an organization serving refugee communities, held listening sessions in 2022 to gauge the needs of Somali American voters in San Diego County. Rahmo Abdi, director of campaigns for the San Diego group, said listening session participants felt unsure and worried about making a wrong voting decision that could hurt their communities.

That’s why multilingual assistance honors the choice of every eligible voter, Abdi added.

“We don’t think we need to wait for federal law to get more access for our community, that’s why we are fighting locally to expand language services,” Abdi said.

Jama attended many of those listening sessions, volunteering as an interpreter. She said she plans to vote in the presidential primary Tuesday, and she will continue helping those who don’t speak English.

“Even if they don’t sign the bill I will keep helping my community, because they want to vote and that’s their right,” said Jama. “That’s democracy.”