Writer Truman Capote, painter Georgia O’Keeffe, composer Igor Stravinsky — each stand alone for photographer Irving Penn, placed in a tightly angled corner, confronting the inescapable lens.

These are some of the dynamic moments found in the Penn retrospective opening Saturday at the de Young Museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

Beautifully hung, over 175 stunning photographs — silver and platinum-palladium prints — span the artist’s career from the late 1930s to the 2000s.

It is important to view Penn’s exhibition in the context of the mid-20th century. Penn’s work was anchored in the world of design, which in post-World War II America was reaching for an international language that might unite humanity following an era of atrocities. The same years Penn was photographing in Africa, anthropologist Margaret Mead was working on a universal graphic language to be understood by members of any culture

Penn’s work embodies a post-war desire for a universal culture. Graphic design in the 1950s dropped decoration, text was placed on a straight grid that was seen as easy to navigate, with sans-serif font. Architecture shed its classical flourishes for pure structural form. Sculpture focused on silhouettes and cubist abstraction. In that same zeitgeist, many of Penn’s photographs look like sculptures.

A student of graphic design, Penn smartly counterbalanced his black and white compositions with positive and negative space. His astonishing skill at evoking an intense presence from his subjects hinges on personal tension. In a 1948 photograph of Marlene Dietrich, the actress is in a suspended gaze as she teeters on a ledge against the weight of her heavy black coat.

These iconic works from the 1950s set a standard for the long marriage of fashion and photography, which continues today.

Among the notorieties he photographed throughout his life were writers T.S. Eliot and Carson McCullers, painter Francis Bacon and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The de Young show features the addition of portraits Penn made in San Francisco for Look magazine during the Summer of Love, including Hells Angels, Jefferson Airplane and hippie families, courtesy of the Irving Penn Foundation. The museum recently acquired into its collection a suite of five portraits Penn took in September 1967 of the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, an experimental troupe led by Anna Halprin.

Penn worked for Vogue magazine in his early years. In the 1950s, he opened his own studio in New York, expanding his opportunities and working in advertising. Penn took his tented studio on distant voyages for Vogue.

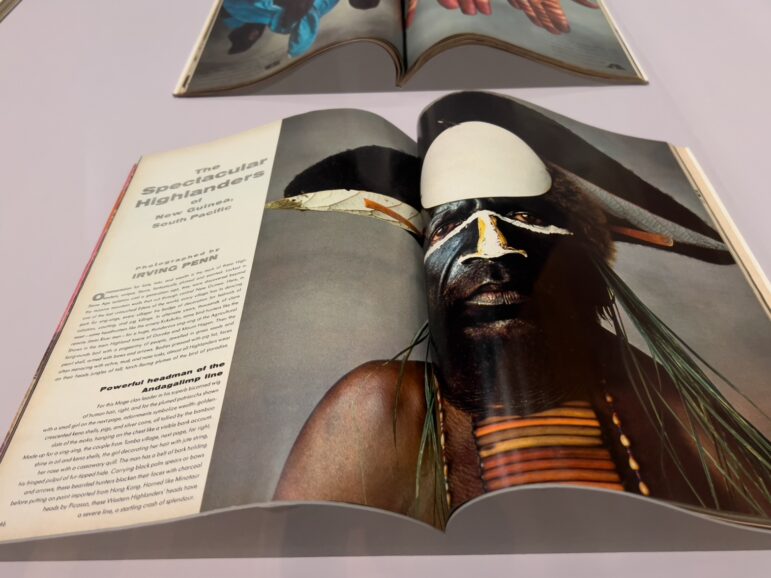

By the late 1960s, Penn was making portraits in the islands of Papua New Guinea, Morocco and the Republic of Dahomey (presently Benin in West Africa). Subjects were photographed with natural light against a muted dropcloth, the same method he used throughout his life.

Published in Vogue under headlines that referenced “beauty” and “adornment,” they were presented as found fashion. The magazines are on display in the de Young, with articles that share cultural details. Some writers even lamented the whitewashing of universal culture.

“The symbolic European model tending everywhere to replace regional styles of dress,” wrote one Vogue author, “the loss of national costumes and of professional uniforms is the most striking sign of ethnic disintegration.”

Abram Jackson, director of interpretation for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, enlisted multicultural scholars for the de Young show who framed the ethnographic portraits with a contemporary social reading.

The exhibition originated from the photography collection at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It toured Paris and Berlin before coming to its only West Coast venue in San Francisco.

“Irving Penn” runs March 16 through July 21 at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco. Admission is $32 general, $29 senior; $23 student; $12 for youth at famsf.org.