California is just starting a statewide effort to create apprenticeship opportunities for young people, ages 16 through 24, as college becomes less affordable for many high school graduates and other costs of living are rising.

But the program has run into a funding snag. Gov. Gavin Newsom, trying to plug a budget hole that some officials say could be $78 billion, now plans to delay $25 million in next year’s funding — about how much the state is spending this year on the effort.

This could be a setback for a new system that funds apprenticeships strictly for young people. Currently most apprentices are older than college age — the nationwide average age of an apprentice is 29 — and most apprenticeship programs feed into the construction trades.

State officials think much younger people should be tapping into this system.

“Not everybody can afford to go onto college, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not bright, hard working people,” said Adele Burnes, deputy chief of the state’s Division of Apprenticeship Standards. “It just means they may not be able to afford to not be earning.

“We as a state want to make sure we’re creating onramps into careers … that offer them that pathway into a family-sustaining wage.”

Those who complete apprenticeships can earn starting salaries of $77,000, and their average lifetime earnings could outpace their peers’ by more than $300,000, according to research by Jobs for the Future, a national organization that promotes workforce development.

Last July the Legislature tasked the Division of Apprenticeship Standards with gathering data and developing a system for allocating money to groups that operate youth apprenticeship programs.

Organizations have until March 15 to apply for funding.

The Division of Apprenticeship Standards has established grants for organizations that develop pre-apprenticeship and apprenticeship programs targeting the state’s 500,000 “opportunity youth” — young people who have dropped out or are at risk of dropping out of school, or who come from low-income families or neighborhoods, or are involved in the foster care, child welfare or juvenile justice systems.

The organizations that receive the grants are expected to develop apprenticeship programs for careers in health care, education, information technology and more.

The effort is in line with Newsom’s stated goal of reaching 500,000 registered apprentices by 2029. So far, the state has about 90,000.

Typically apprenticeship programs are federally registered and involve at least 144 hours of classroom instruction and 2,000 hours of on-the-job work under the supervision of a professional.

Those who complete apprenticeships usually secure union jobs with living wages and benefits, said Taylor White, who helps design youth apprenticeship systems for New America, a national research and advocacy nonprofit.

Historically apprenticeships mostly fed the building and fire trades. Many union jobs require employees to be over 18, White said.

The national decades-long “college for all” push in high schools has steered young people by the droves toward four-year colleges. But college hasn’t worked out equally for everyone.

“That hasn’t necessarily resulted in the closure of the workforce and economic disparities that people expected it would,” White said. It’s now clear that young people need more options, she added.

While various pre-apprenticeship programs in the state prepare young people for apprenticeships, California has yet to create a central youth apprenticeship system to recruit workers who may still be in high school or college.

The state established a Youth Apprenticeship Committee that is expected to provide recommendations to the Division of Apprenticeship Standards in July.

One example of a new high school apprenticeship program is San Joaquin County’s Apprenticeships Reaching Career Horizons, the first of its kind in the state.

Three of the six young people who started at its beginning in 2020 have since completed the three-year program. To date there have been 25 students in the program, said Pam Knapp, director of college and career readiness at the San Joaquin County Office of Education. Students can train as teaching aids, assistant farm managers or hospitality marketing professionals.

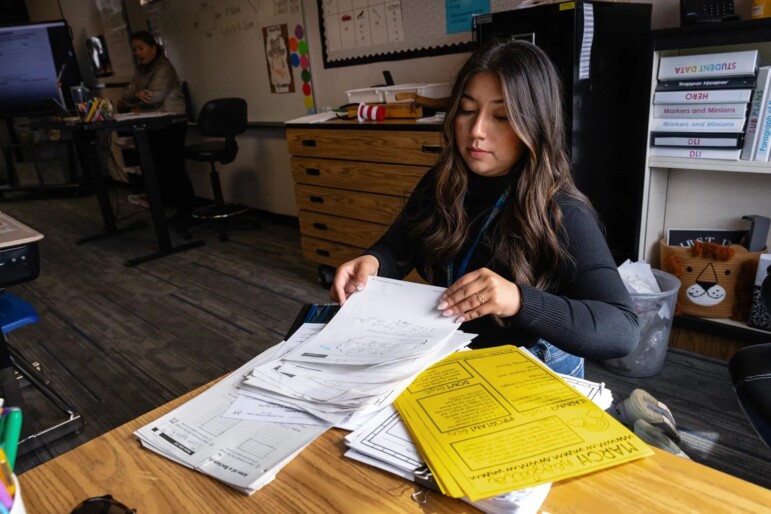

When Catalina Govea, a Linden High senior, applied to the program, she thought she was applying for a summer job. It turned out to be a lot more, she said.

“Once I got the position, I immediately fell in love because I knew I wanted to be a teacher,” Govea said.

Govea works in Linden Elementary classrooms and in afterschool programs as a teacher’s aide, assisting teachers with administrative work and students with assignments and learning about classroom management.

She also takes online college courses on childhood and adolescent development, child discipline and other education topics that will transfer when she starts at Sonoma State University in the fall.

The program, Govea said, has helped her mature and handle stressful classroom environments, experience she might not have otherwise gained until years later.

The experience was “perfect to know what my future would look like,” she said.

Knapp said the apprenticeship program works well because the county Office of Education functions as an intermediary between employers, school districts, and the state Division of Apprenticeship Standards.

But the program has faced challenges convincing enough employers to hire teenagers, she added.

There are higher workers compensation rates for workers under 18, so private companies may be hesitant to hire them, Knapp said. And unions representing school workers are hesitant to hire teenagers if those jobs could instead go to union employees, she added.

“That’s been the heavy lift,” Knapp said. “If we want to expand this, then legislatively there needs to be some sort of an incentive, some sort of a tax credit, anything for employers to invest in the youth.”

In the Bay Area, the Construction Trades Workforce Initiative is running its pre-apprenticeship programs as a pipeline for high school students interested in such fields as construction and plumbing.

Beli Achary, the initiative’s executive director, said the program has done a lot of outreach work to educate school counselors and employers about the importance of opening up apprenticeships to youth. The initiative also visits high schools in the Bay Area to inform students about the careers they can explore through apprenticeship programs.

The initiative oversees, funds and authorizes several pre-apprenticeship programs with school districts and juvenile detention centers across the Bay Area. They are in the process of developing programs for at least five more school districts and Laney Community College in Oakland.

“The attitude has shifted and is a lot more positive,” Achary said. “Workforce development is becoming more and more of a buzzword, which is a good thing.”

Traditional apprenticeships, mostly in the building and fire trades, have skewed white and male.

Across the country, 63% of youth apprenticeships have gone to people who identify as white and 35% to those identifying as nonwhite, according to the Jobs For the Future report, which analyzed data for 2010 through 2020.

Women and girls make up 7% of all youth apprentices nationally.

After an apprenticeship, the average starting wage for youth apprentices was $31 an hour, the study said: white youth earned $29.55, Latino youth earned $32 and Black youth earned $23, it said.

While young men’s pay averaged $13.08 an hour, males who had apprenticeships earned $31 an hour, a 137% boost. For young women, those with apprenticeships earned 42% more than the average, the study said.

The report says occupational segregation is key to starting wage disparities, highlighting the need to recruit to diversify various occupations.

For example, the top occupation for women apprentices was pharmacy technician, which nationally paid $12 an hour. The top occupation for male apprentices was electrician, which paid $26 an hour, according to the report.

“Providing more information and awareness, I think, will be a key part of working through some of those inequities,” said Myriam Sullivan, a researcher on the report. That includes educating employers on how to keep diversity in mind when hiring and informing young people about wages in various career paths.

Sullivan said some of the lack of diversity in apprenticeships may have to do with how they’re funded. Because grants typically incentivize high enrollment, that leaves little room for program leaders to think strategically about hiring diversely, she said.

California’s apprenticeship grant language targets groups that serve youth who are typically shut out of these opportunities, said Burnes, of the state apprenticeship standards division. The state program also tries to ensure organizations can support youth through the completion of their programs.

“What we heard resoundingly was just how important supportive services are to opportunity youth who are trying to get into apprenticeships,” Burnes said. They “face unique life challenges and barriers that might make their success in a program a step harder.”

Eric Morrison-Smith, executive director of the Alliance for Boys and Men of Color, a national youth advocacy network which co-sponsored California’s youth apprenticeship legislation, said the priority must be ensuring young workers have more options than they’ve had in the past and building worker power.

“I think the pendulum is shifting a bit,” he said. “Historically the pendulum has leaned heavily on the side of ‘college is the only way to get a good job.’ We believe we need a solid ecosystem of economic opportunity that allows for people to make decisions that will give them more self determination over their lives.”

Morrison-Smith said supporters of the Youth Apprenticeship program are lobbying Senate and Assembly leaders to ensure it remains a priority in budget negotiations.