Before Thomas Guskey became a leading academic expert on grading and assessments, he was a middle school math teacher.

One day he was chatting with an 8th grade student, who he described as a “superstar,” and asked if she had studied for that day’s exam. He was shocked to hear she hadn’t.

“Well Mr. Guskey,” he remembers her saying, a quizzical look on her face, “I worked it out. I only need a 50.2 to get an A [in the class]. I don’t need to study for a 50.2.”

This was a moment of realization for him. “This 8th grader had worked it out to the tenth decimal place what she needed to do to get an A in my class,” he said. “And she was surprised I didn’t get it. And I thought, ‘Wow. What have I done?’”

For this student — and so many others — school was not about learning. It was about getting a good grade. And with flawed traditional grading systems, those two outcomes didn’t always coincide.

Every time Guskey tells this story to other teachers, he said they shake their heads and share similar anecdotes of their own. Other experts in the field echo these sentiments, noting that schools have spent far too long grading students based on whether or not they turned in a pile of work or showed up to class on time, rather than focusing on if a student has learned academic content. This can ultimately lead to final grades that inaccurately reflect and communicate what kids actually know.

Today, as schools combat post-pandemic learning gaps, it’s become even clearer that traditional grades are not precise communicators of learning. In some cases, this leads parents to believe their kids are performing at grade level, when in reality they’re falling behind.

As educators push for more clarity and transparency, a number of schools and districts are turning to what’s known as standards-based grading, a system and communication tool that separates academic mastery from behavioral factors. When done correctly, it should more accurately reflect what students know and correct for both inflating — and deflating — grades.

But a misunderstanding of standards-based grading’s true principles, a lack of proper training for educators and a rush to quickly adopt a complex new system often leads to messy implementation, various experts told The 74. And, they warn, districts looking for support are turning to grading consultants, a number of whom aren’t qualified in the field.

“So many districts are getting into this and they’re failing miserably,” said Guskey, the grading and assessment expert and professor emeritus at the University of Kentucky College of Education.

“Schools are jumping into this without a clear notion of what they’re doing and what the prerequisites are to being standards based,” he continued. “And then when problems arise, they have no recourse except to abandon [it] completely.”

As schools look for an effective fix to learning gaps, “standards-based grading is one that seems like it can be a quickly adopted effort. But it could backfire and does backfire very easily,” said Laura Link, associate professor of teaching and leadership at the University of North Dakota.

In a 2022 paper she and Guskey wrote, “although many schools today are initiating SBG reforms, there’s little consensus on what ‘standards-based grading’ actually means. As a result, SBG implementation is widely inconsistent.” This creates uncertainty, confusion, frustration — and resistance, which can ultimately lead to it being tossed aside, the authors said.

The many meanings of a “C”

Standards-based grading is not new. While it’s challenging to pin down just how many schools are currently using it, post-pandemic interest in a system that’s seen as more accurate and equitable appears to be growing.

Link is now working with the Bethlehem, Pennsylvania school district on implementation. It can also be found in at least one school district in the San Francisco Bay Area and is particularly prevalent in schools in Wyoming, New Hampshire, Maine and Wisconsin, with more cropping up in Connecticut, New Mexico, and Oregon, EdSurge reported in November.

Another expert, Cathy Vatterott, who wrote Rethinking Grading: Meaningful Assessment for Standards-Based Learning and is professor emeritus of education at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, said: “After we got through COVID, all of a sudden I started getting offers to come and speak to people about standards-based grading.”

Regardless of what model teachers practice, they typically grade using three different criteria: what academic skills students have learned and are able to do, such as solving for “x” in an algebraic equation; what behaviors they bring that enable learning, such as attendance and turning in work on time; and how much they’ve grown and improved.

In traditional models, teachers combine these three, muddling them together and assigning a single mark for an assignment — often a letter grade or a percentage. At the end of a semester, these assignment scores get averaged into a final grade that goes onto a transcript or report card. Proponents of standards-based grading argue that this presents an unclear and inaccurate picture to parents, students and colleges.

“It makes the grade impossible to interpret,” according to Guskey. For example, a “C” on a paper could mean the student really only understood the material at a “C” level or it could mean they turned in an excellent paper but two weeks late. Further adding to the confusion: what goes into a grade is inconsistent from teacher to teacher and school to school.

Traditional grading not only presents accuracy concerns but also equity ones, according to Matt Townsley, assistant professor of educational leadership at the University of Northern Iowa. “For example, if we award points for assignments that are completed on a daily basis — called homework — outside of class, you can imagine a scenario where some families are more privileged in their ability to do it,” he said.

Some students have access to a quiet place to work, tutors, parents who can help them with assignments, and other key resources, while others work after-school jobs or take care of younger siblings. When teachers grade homework, experts like Townsley argue, they are grading for these factors, rather than what students have actually learned.

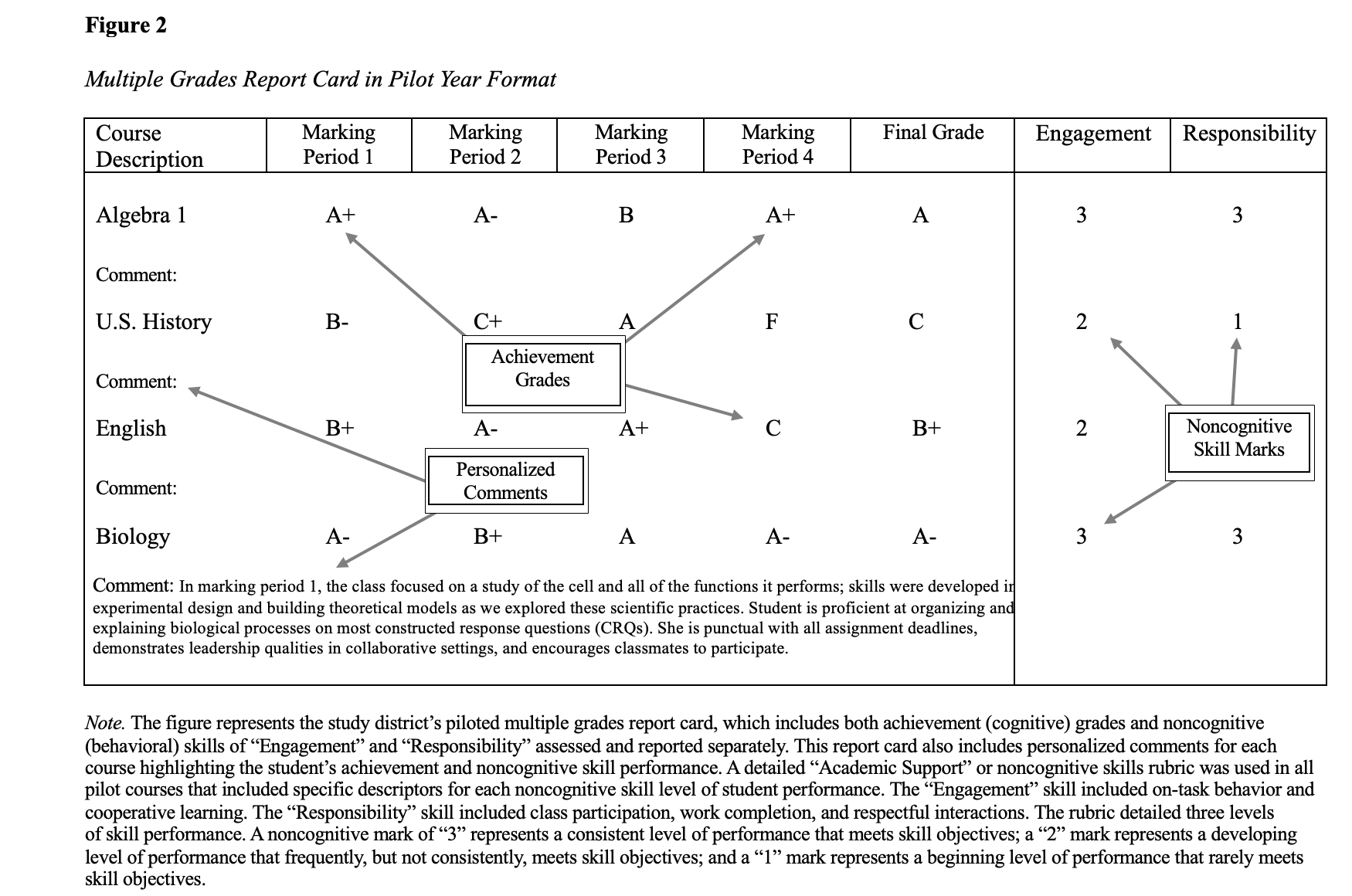

To combat this, standards-based grading does it differently. Rather than lumping together academic, behavioral and improvement grades, it separates them and reports them out individually in what Link calls a “dashboard of information.”

Too often, she said, consultants and other self-proclaimed experts, who are not researchers, will push to throw away behavioral grades altogether. But she warned “that becomes problematic very, very quickly. We shouldn’t be using our gradebooks to punish and control. But those factors — those behavioral factors — are academic enablers, and we know that to be true as well.”

Reporting it out separately makes students recognize that these other components still count and, in some ways, it makes them each count more because they can no longer be disguised by other factors, like extra credit, according to Guskey.

It’s important for schools to decide upfront what behaviors they want to prioritize — whether that’s attendance, work ethic, responsibility — and then build a guide on how teachers will score for them. “By giving these kinds of dashboards of information, it helps colleges, trade schools, etc., have a deeper understanding of what kind of students they’re accepting into the programs and what kind of support they will need in college,” Link said.

The academic grades should be based on grade-level standards and learning objectives, like the ability to find strong evidence to support a claim if a student is writing a paper or answering a test question.

A second key criteria is moving away from handing out percentage grades based on 100 to using a much smaller measurement scale, like 0 to 4. On each standard, students could also be graded as “exceeding,” “meeting,” “almost,” or “not yet.” Guskey noted that while this all may sound novel and unusual, other countries around the world, including Canada, have been using these practices for decades.

A third component — providing students multiple opportunities to demonstrate their understanding and mastery of a standard — is often where the greatest controversy crops up and things are most likely to go awry. Some educators argue that students should receive limitless opportunities to redo specific assignments. Researchers such as Link, though, argue that while students need multiple opportunities to demonstrate their understanding, that does not necessarily mean redoing the same assignment.

“This is where a lot of non-academic proponents encourage that standards-based grading means you give as many retakes as it takes for mastery. Not true. Not true. That’s an assessment issue. That’s not a grading issue.”

So, while a second chance at one assignment is perhaps the fair thing to do, it is not inherent to the ethos of standards-based grading. She emphasized that if schools do implement retake policies, the process needs to be purposeful: If a student doesn’t get it the first time, they need to get corrective feedback and instruction. But “if they don’t get it on the second chance, you’re going to record their grade and move on,” she said.

There is no empirical evidence supporting the benefits of endless retakes and, she added, such practices can be a time-consuming and unrealistic ask of teachers.

Because many of the people who write about and consult on testing don’t fully understand what’s behind assessing students more than once, Guskey said, their recommendations on how best to do it are often untested and can’t be supported in practice. Their inconsistent advice, he said, can lead teachers and administrators to forsake efforts to reform grading.

While it’s important to understand what standards-based grading is, it’s also essential to debunk what it’s not. At its core, experts say, it’s purely a communication tool. It doesn’t tell educators how to create assessments, build curriculum or manage behavior. It can make space for teachers to provide more individualized feedback and for students to move through the skills and knowledge they need to master at their own pace. But these things aren’t inherently a part of it.

“Basically everything is just to pass.”

When Kenny Rodrequez became superintendent of the Grandview school district a decade ago, he knew the grading system needed to change. He was concerned that as it stood, the traditional grading model they relied on wasn’t communicating students’ progress to their parents accurately. Leaders in the district, located just outside of Kansas City, ultimately decided to shift to standards-based grading for kindergarten through 6th grade.

Now, in his eighth year as superintendent and ninth year overseeing the transition, he feels good about what they’ve accomplished. One key factor of the successful implementation, he said, was “not trying to do it all at once.” It can be tempting to “just say, ‘Let’s bite the bullet and let’s just roll it all out at the same time,’” he added. It was important, though, to fight this urge and instead find a balance that allowed for deliberate policy shifts that still didn’t take an inordinate amount of time to implement.

Another key factor: making sure there was strong teacher and parent buy-in. The first year in particular, staff was nervous to explain this new system to parents before they even fully understood it themselves. Rodrequez said they created talking points for teachers and gave them the resources they needed.

In the future, the district plans to bring standards-based grading to 7th-12th grade classrooms, but he anticipates at the high school level this will be trickier. “Our challenge … is nationally we still have a system that’s still pretty based upon our letter grades. And that system’s been around for so long and never was designed to do what we’re trying to get it to do right now.” Demands for GPAs and class rankings, in particular, are incongruous with the standards-based model but often necessary for college applications.

These very challenges have played out in one New York City high school, according to parent Talia Matz. When her stepson started ninth grade at Future High School in Manhattan, the school had orientation sessions to explain to parents how their standards-based grading system works. Still, she and her husband were skeptical. And over the past three years, they’ve only become more concerned, she told The 74.

Some of the major assignments that the school uses instead of statewide Regents exams “are a bit of a joke,” she said, and students are not held accountable. “Basically everything is just to pass. It doesn’t matter how well you do,” she said, adding, “it doesn’t seem like there’s any love of learning. It’s just kind of to get it done.”

Contrary to best practices, on his report card there are no separated out comments or grades about behaviors. All standards are scored on a 0-4 scale, and parents and students can see grades on an online platform called JumpRope. But, the school then converts this scale into a traditional percentage grade, which is ultimately sent to colleges — another big no-no, according to experts. (According to the NYC Department of Education’s website, schools may choose from a number of grading scales, including A-F, but it appears that regardless of what they select, all grades are ultimately converted into percentages.)

An example of a School of the Future High School transcript. Grades are not separated out by standards and have been converted into percentages, two practices standards-based grading experts warn against. Parents are encouraged to look online for access to a breakdown of grades. (Talia Matz)

Students have a number of opportunities to redo assignments and no clear consequences for late work, Matz said. Rather than getting grades on daily assignments, he gets a “Work Habits/Independent Practice” score, which his stepmom said never appears on a transcript. This, she said, provides no incentive to turn assignments in on time or get them right the first time.

School administrators did not respond to requests for comment. The school’s website contests this point: Their official policy states that the “Work Habits/Independent Practice” score becomes 10% of a student’s final grade. Never reporting the behavior grade or averaging it into a single final grade would both go against standards-based grading best practices.

Matz fears all this lends itself to lowered standards, which will leave her son unprepared for college. In the fall, he’ll enroll at SUNY Buffalo, “but we’re concerned because there’s going to be different expectations … You have to study on your own, you don’t necessarily get second or third chances.”