Two months ago, a robbery suspect in a high-speed car chase struck Ciara Keegan’s Honda CR-V while fleeing police. Keegan, 25, had been on the phone with her boyfriend making dinner plans when she saw the suspect’s car bearing down on hers.

“All (my boyfriend) heard was the crash, my screams, the sirens of police cars,” Keegan, 25, told CalMatters in a phone interview. Seeing smoke after the crash, she worried that her car would set on fire. “As I was being loaded into the ambulance, I saw the other car completely engulfed in flames,” she said.

The chase ended in Oakland but began in Chinatown in San Francisco, where in March voters will decide on Proposition E. The wide-ranging measure would loosen restrictions put on police use of surveillance technology in 2019 and allow police to use drones in high-speed chases, among other things. The local measure could have statewide implications for law enforcement, as policies adopted in one California city can be copied elsewhere.

“What we’re seeing in San Francisco isn’t limited to San Francisco,” said Saira Hussain, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights advocacy group. “It has implications for other cities and jurisdictions as well.”

Police and Prop. E supporters say using drones in car chases will reduce injuries. Keegan is skeptical.

“I’m worried police chases will increase in frequency and more people will get hurt and there will be less safeguards for the general public and San Franciscans will be treated like collateral damage,” said Keegan, who was born and raised in San Francisco.

Prop. E would allow police to test surveillance technology for a year or more unless the County Board of Supervisors intervenes, and gives police the power to deploy cameras and drones without oversight. Prop. E rolls back a 2019 law that bans use of face recognition by police and requires public disclosure and debate before police obtain new forms of surveillance technology.

“This is an important moment where powerful interests are trying to attack oversight and limitations on their power,” said Matt Cagle, a senior staff attorney for the Northern California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

San Francisco is one of the largest major cities to adopt surveillance technology oversight championed by the ACLU. In recent years, half a dozen cities from Oakland and Berkeley in the Bay Area to San Diego in southern California have adopted similar policies, but efforts are underway to reduce those powers. In December 2023, San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria proposed amendments that civil liberty advocates argue water down surveillance technology oversight. Hussein points to AB 2014, a bill proposed last month by Assemblymember Stephanie Nguyen, a Democrat from Elk Grove, as another attempt in this vein. That bill would enable unarmed drone donations from the US military to state and local law enforcement agencies.

San Francisco set a standard for civil liberties protections when it passed a law that makes public comment and local governing body approval of new police uses of surveillance technology, said Hussain. She said that if Prop. E passes it has implications in other parts of California where lawmakers may consider policy that puts unilateral decisionmaking power about tech adoption in the hands of police.

The pendulum has swung toward public oversight in recent years and rightfully so, said Yes on Prop E spokesperson Joe Arellano, but people are fed up with seeing small businesses get burglarized. He said Prop. E gives police the power to initiate pursuit of people accused of committing property crimes but doesn’t make it a mandate.

Police currently have discretion to pursue any suspect deemed a risk to public safety regardless of the crime they’re suspected of committing.

“Our officers are highly trained and should be trusted to make smart decisions about these incidents,” Arellano said.

Reggie Jones-Sawyer, the Democrat Assemblymember from Los Angeles and chair of the public safety committee, said measures like Prop. E can have unintended consequences.

“You could implement this [Prop. E] and find out later that it causes more problems than you anticipated,” said Jones-Sawyer, who recalled being falsely identified as a criminal by face recognition along with other members of the California legislature back in 2019.

“That showed a flaw, so with any new technology whether it’s drones or others we really need to look at all the ramifications that can come about.”

There were 42 San Francisco car chases in 2023, according to California Highway Patrol records obtained by CalMatters. By comparison, 28 car chases a year occurred on average from 2018 to 2022. There was also a higher than average number of injuries and deaths last year.

Now Prop. E, which is supported by San Francisco Mayor London Breed and bankrolled with more than $300,000 from tech tycoons, asks voters to change vehicle pursuit policy to allow police to chase suspects for misdemeanor crimes and use drones along with or in lieu of vehicular pursuits. Police in many major cities limit pursuits to violent crimes and suspects who pose a serious threat to public safety.

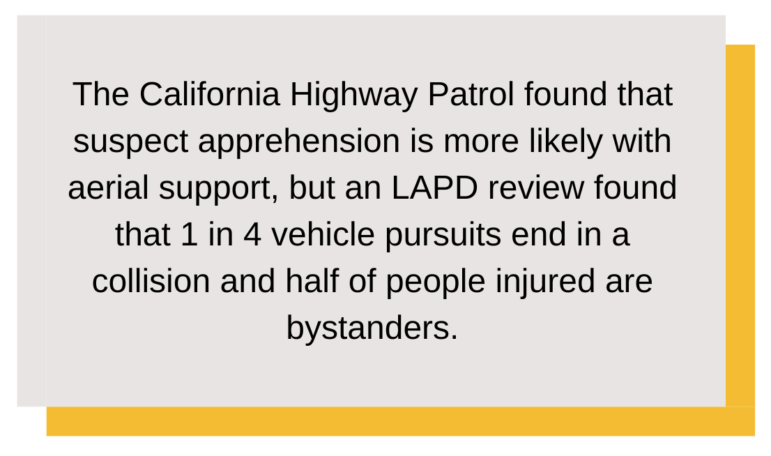

High-speed vehicle pursuits resulted in 56 collisions from 2018 to 2022 in San Francisco. Forty percent of chases resulted in a collision and 1 in 6 chases resulted in an injury to a suspect driver, police officer, or bystander, according to the California Highway Patrol.

Vehicle pursuits of suspects led to 52 deaths statewide in 2021, according to a highway patrol report, and roughly 1 in 3 crashes involving police pursuit of a suspect resulted in an injury.

Supporters say drones can play a role in high-speed vehicle pursuits and possibly reduce injuries to bystanders and police officers by reducing the number of police vehicles involved. The ACLU and other groups that oppose Prop. E say it guts hard-won reforms and endangers the public, officers, and suspects by authorizing high-speed chases for low-level crimes in one of the densest cities in the country.

Cagle says he wants proof that drone involvement in police car chases won’t make things worse.

“The idea of having drivers flee police cars as well as having to look over the shoulder to figure out where the police drone is as well doesn’t seem like a recipe for safer police car chases or public safety generally for pedestrians and people in the city,” he said.

A 2023 ACLU report found that more than 1,400 police departments in the U.S. use drones today and that drone-as-a-first-responder programs are on the rise. In 2017, the Chula Vista Police Department in San Diego was the first in the nation to receive a federal aviation administration exemption allowing drones to operate outside of the sight range of their pilots. So far this year, the Chula Vista Police Department has sent drones in response to roughly a quarter of 911 calls for service. Elsewhere in California, police in Fremont, San Pablo, and Santa Monica are exploring drone-as-a-first-responder programs.

The claim that drones can stop high-speed vehicle pursuits features prominently in promotional material distributed by companies that sell drones to police. At a debut in San Francisco’s Marina District last fall, Skydio introduced X-10, a drone that can fly in the dark at speeds of 45 miles per hour. Once X-10 locks on a target, the drone can follow people and vehicles from high in the air, so speed isn’t as much of a factor.

Skydio CEO Adam Bry discussed ongoing efforts to enable drone-as-a-first-responder programs in other U.S. cities, including New York, where vehicle pursuits are on the rise and police envision autonomous drone deployments. Skydio partners with Axon, a company whose AI ethics oversight board resigned in protest following a pitch for autonomous Taser-mounted drones.

The California Highway Patrol found that suspect apprehension is more likely with aerial support. In Los Angeles, police prioritize air support from helicopters when considering whether to pursue a fleeing suspect or known risk to public safety. But an LAPD review ordered last year by the Board of Police Commissioners following a rise in injuries found that 1 in 4 vehicle pursuits end in a collision and half of people injured are bystanders.

Los Angeles allows high-speed pursuits for misdemeanors, as Prop. E would allow in San Francisco. San Francisco Chief Bill Scott told the police commission the department is developing drone use policy but currently does not use drones or helicopters.

At the same meeting, Department of Police Accountability Policy Director Janelle Caywood evaluated the department’s vehicle pursuit policy and compiled a report on vehicle pursuit best practices.

She called current vehicle pursuit policy average compared to other U.S. cities. She also noted that injuries and deaths are on the rise in some major cities. In New York City, police pursuits are up 600%.

Caywood recommended using drones to reduce the need for pursuits and de-escalate incidents. If use is limited to crimes in progress and vehicular pursuits, she told the commission drone use may be worth discussing, but that drones should go through the surveillance tech oversight process put into place in 2019 to ensure safe use and protection of civil liberties. She also recommends exploring use of devices that shoot GPS trackers at fleeing vehicles.

Cagle said he fears increased drone use could result in privacy violations and higher levels of surveillance of communities of color. Community members expressed a similar concern in 2022 when arguing that San Francisco’s police department should not have access to killer robots.

Chinese for Affirmative Action is a civil rights group based in San Francisco that’s part of a coalition of community groups, including the ACLU, that oppose Prop. E.

“We’ve seen how police chases have led to the deaths and injuries of our community members in San Francisco,” said the group’s community safety and justice policy manager Nhi Nguyen in an email.

Nguyen believes that if Prop. E passes, it could have implications for other municipalities when elected officials try to expand tools for local police in an election year. She argues the root cause of public safety concerns is access to housing, education, health care and economic opportunity. “We can’t police chase and surveillance our way out of socio-economic problems,” she said.

Body cameras and use of force

If passed, Prop. E would also allow body-worn cameras to satisfy reporting requirements in incidents involving police use of force.

The San Francisco Police Department is 18 times as likely to use force on Black residents compared to white residents and 5 times as likely to use force on Hispanic residents compared to white residents, according to data released in November 2023.

A 2022 California Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board report also found that the department is also more likely to use force against people who identify as transgender and people with mental health conditions.

Prop. E will make it harder for community members to know how many use-of-force incidents are taking place in San Francisco, which puts lives at risk, said Sana Sethi, spokesperson for the SF Rising Action Fund, which also opposes the measure. She fears that other cities may adopt similar policies and expand surveillance if Prop. E passes.

Since crime in San Francisco attracts so much media attention, she’s concerned that passage of Prop. E will amplify a narrative that distracts from evidence-based solutions to crime reduction like access to housing, health care, and substance abuse treatment.

“Prop. E would bring a new standard of lack of oversight on harmful tactics, not only here, but throughout California,” Sethi said.