One of modern civilization’s most pressing questions is not just how to live longer, but how to live better as we age? Dr. Paul Alan Cox thinks the answer lies in the food we eat.

As an ethnobotanist, Cox and his research team study indigenous people and their mostly plant-based diets to aid in the development of drugs addressing neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. “While others focus on the symptoms of these diseases, we focus on the causes,” he told a standing room only crowd at the Piedmont Community Center this past Wednesday.

Sponsored by the Piedmont Garden Club, Cox’s presentation shared research he’s conducted around the world that compares patterns of disease and wellness in island villages to discover causes and treatments.

In Guam, his team focused on two villages where the Chamorro people had a hundred times the rate of ALS as elsewhere in the world. It was eventually determined that a neurotoxic amino acid called BMAA found in cycad trees had something to do with it. Villagers consumed BMAA through tortillas made from cycad seed flour. In addition, they ingested a larger amount of the toxin in a stew made from flying foxes (large bats) that feast on cycad seeds.

Cycad tree, aka sago palm

Years of research to support the lab’s theory that BMAA is linked to ALS. Now a study from independent researchers also reports a link, strengthening claim (from Brainchemistrylabs.org)

BMAA is produced by “cyanobacteria”— a word Cox prompted the audience to repeat at multiple points in his lecture—which manifests as a blue-green algae (above right). Cyanobacteria are among the oldest organisms on Earth and are found in marine, freshwater and terrestrial environments. (It shows up in the roots of the cycad tree.) Cox’s research points to BMAA’s role in protein “misfolding” in the brain. This causes tangled diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, which he illustrated through images of tangled Slinky toys.

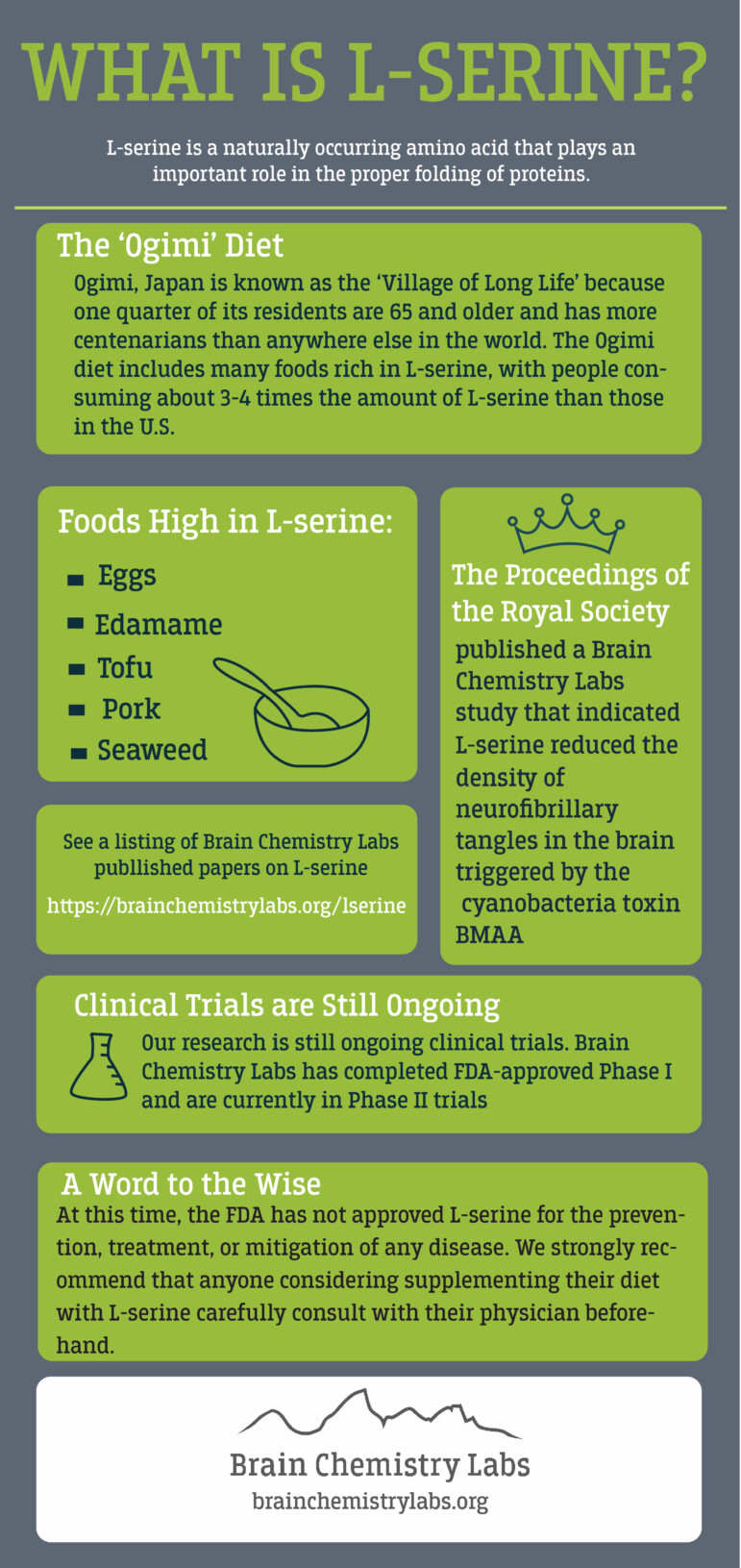

An exciting development in research conducted with Australian colleagues indicated that another amino acid, L-Serine, might block the effects of BMAA.

As part of his team’s ethnobotany research, they traveled to Okinawa to study the mostly plant-based diet of people with unusually good health. Members of the Ogimi village experience extreme longevity with few to no neurodegenerative diseases. Cox discovered that their diet—which includes tofu, sweet potatoes, and seaweed—is rich in L-Serine.

Foods rich in L-serine (Julie Reichle)

Dr. Cox with centenarians in Ogimi village, Okinawa (from Brainchemistrylabs.org)

“If you could see these villagers, it would totally change your view of aging,” said Cox, after playing a video of a 98-year-old woman moving with the fluidity of a ballerina, noting her capacity to clearly recall life events.

Cox described a similar clarity in his interviews with other villagers. For example, when he’d ask them to “tell him about the War,” they’d counter “which war?” When he’d clarify that he was asking about the World War, they’d reply “which World War?” implying that some were old enough to remember WWI.

Further research with vervet monkeys on the island of St. Kitts confirmed the theory that L-Serine may block the effects of BMAA.

Dr. Cox has been awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize—sometimes known as the Nobel Prize of the Environment—and was named one of TIME magazine’s eleven “Heroes of Medicine” for his efforts in discovering new drugs from tropical rain forests. The Garden Club of America—of which Piedmont Garden Club is a member—has awarded him its two top honors—a GCA Medal and Honorary Membership.

He obtained his PhD from Harvard but began his career at UC Berkeley and has since established the Berkeley-based Seacology Foundation—an environmental organization that partners with indigenous people to protect millions of acres of rain forest and coral reefs throughout the world. Now based in Jackson, Wyoming, Cox leads Brain Chemistry Labs, a not-for-profit organization with a grassroots consortium of fifty international scientists working to further this research.

To the gathered crowd, keen for advice on how to stave off disease, he offered dietary advice—primarily to eat a Mediterranean diet and foods that are high in L-Serine—and advised they avoid cyanobacteria. When asked about growing cycad trees in a home garden, he offered a raised eyebrow.

Of course, good health is composed of several factors. But Cox’s encouragement to think of our gardens as potential pharmacies for neuroprotection was rich food for thought.

To learn more about Dr. Cox’s research visit brainchemistrylabs.org. NOTE: The information shared in Dr. Cox’s presentation is for educational purposes only and is not intended as an endorsement by PGC of any treatment or product.