Anyone who has played video games knows that they do one thing well: Keep score. At any given moment, players know what level they’re on, how many points or kills or badges they’ve earned and how far they must go to win.

Oh, and they’re fun.

That sophistication — and a bit of that fun — may soon be coming to school assessments.

Educators and developers are increasingly looking to the digital world of games and simulations to make tests more stealthy, playful and, they hope, useful. In the process, the new assessments may also push schools to become more creative.

“The idea is: Can assessment be more embedded?” said Y.J. Kim, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Can assessment be more exciting? Can assessment be more flexible?”

In November, NWEA, which publishes the widely used MAP Growth tests, unveiled a 3D digital assessment on the popular Roblox gaming platform that tests how well middle-schoolers have learned Newton’s Second Law of Motion.

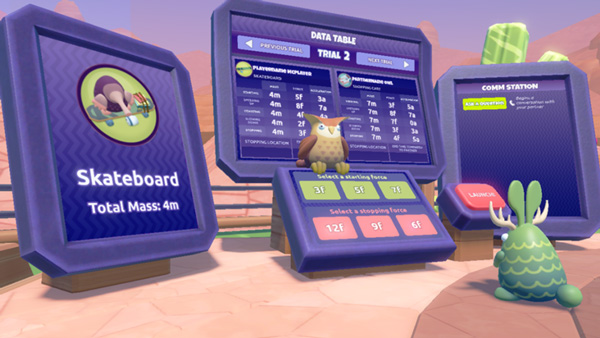

The game, called Distance Dash, requires two students to work together to launch vehicles of different sizes and payloads. The goal: Get both to the finish line in perfect sync.

Students pick a skateboard, a bike, a grocery cart or an automobile, load each with different items, then collaboratively fine-tune the forces placed on them. The whole time, the game covertly measures several objectives, including whether students understand the principles of acceleration and how to apply optimal force.

Tyler Matta, NWEA’s vice president of learning sciences engineering, said the assessment grew out of the Next Generation Science Standards, which require students to analyze and interpret data and understand patterns.

He said helping design it was a stretch for NWEA test makers, who hadn’t previously worked with game designers. “We got to see what goes into building educational games, which was all very novel for us. We learned a ton.”

The organization is working with developer Filament Games, which has produced dozens of education titles.

“As an assessment, it’s important that you actually have the ability to fail,” explained Filament’s Kenny Green, the project’s producer. The data it generates — for instance, how many times students tried and what modifications they made — are all important for teachers to see.

The new exam appears as Roblox, the popular gaming platform, moves further into schools. Last October, it said it’ll spend $15 million to expand educational experiences on its platform, two years after an initial $10 million outlay.

Rebecca Kantar, Roblox’s head of education, said physics lends itself well to such collaborative simulations. Distance Dash, she said, is “representative of the kind of team-based problem solving real scientists do when they’re working through a physics problem in real life.”

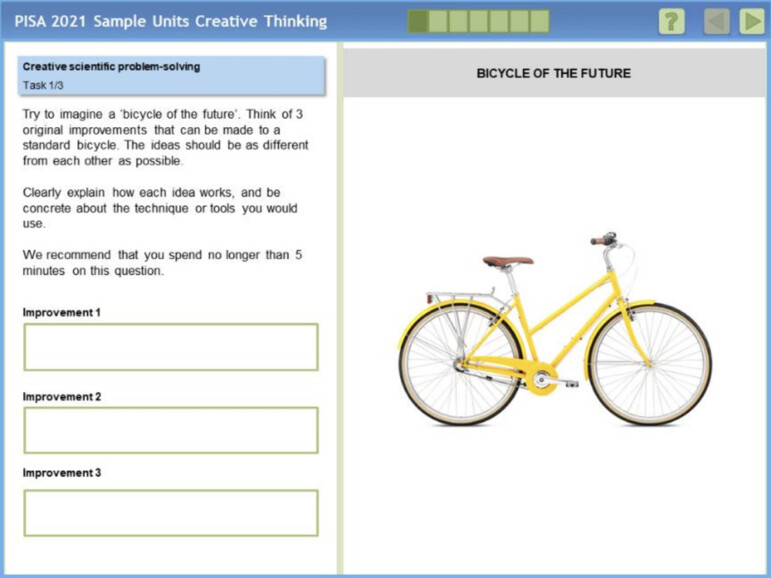

Another recent development: In 2022, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development assessed creative thinking for 15-year-old students in more than 60 countries via the PISA Creative Thinking assessment, which boasts interactive items that allow students to submit drawings with a digital tool.

The test also includes open-ended tasks with “no single solution but multiple correct responses,” organizers said. The first results are expected this year.

Advocates hope to someday make tests more personalized and, in many ways, indistinguishable from games, said Bo Stjerne Thomsen of the LEGO Foundation. “What we hope is that playfulness becomes a serious part of assessment,” he said.

Better still, more playful tests, he said, could open the door for schools to offer more creative, inquiry-based learning.

He and others who are support the new tests don’t mince words: They envision a world where the kind of high-stakes, multiple-choice tests we all grew up with give way to assessments that for the first time allow teachers to capture a broader array of “non-cognitive qualities” such as teamwork and creativity, while keeping students focused on learning.

“Every time you try to pause an experience or stop a learning experience, it actually stops the engagement,” said Thomsen. It’s the same with play: “As soon as you start measuring play, the play stops.”

‘It’s about you engaging with someone else’

Tests can also be demotivating, even though they’re designed to help students show what they’ve learned, said Yigal Rosen, who led the creation of the PISA test.

He recalled interviewing fourth-graders who had taken NAEP science exams: At least one-third of the questions, according to students, were “super boring” and not engaging.

“They will skip them,” Rosen said. “They will just select ‘Whatever.’”

Now the chief academic officer at BrainPop, the learning software company, Rosen recalled that when his team tweaked the NAEP test with a “playful version” that invited students to work together, he said, scores rose by 50%. “It’s no longer about you just responding to this dry prompt,” he said. “It’s about you engaging with someone else.”

When they think of playful assessments, most teachers probably think of digital tools like the popular learning platform Kahoot, which allows teachers to create game show-like quizzes and polls that engage students on mobile phones and other devices. Louisa Rosenheck, Kahoot’s director of pedagogy, admitted that testing, for all its progress, is “still an underdeveloped, untapped area.”

Digital tools like Kahoot that help teachers do informal assessments as they teach are helpful because they “feel more low-stakes” than traditional tests. “It’s very quick, it’s informative. You can get feedback very, very easily,” she said. “But the question types, the formats, often are still kind of discrete items.”

In that sense, she said, they don’t take advantage of what good games can do: Collect extensive data on students’ thinking and decision making — much more important indicators than whether they got the correct result. But that’s expensive, so many educational games simply assess how far a player gets and how many tasks or levels she completes.

‘Stealth assessment’

Researchers have been toying with the idea of more playful assessments for decades. Nearly 20 years ago, researcher Val Shute began looking at ways to seamlessly weave tests directly into the fabric of instruction.

Shute devised the idea of “stealth assessment,” a system that discreetly tests students’ learning in interactive and immersive environments such as digital games.

Aside from offering a less obtrusive way to measure learning, stealth assessment aimed to help with “flow,” the mental state in which a person is so engaged and exhilarated by a task that they forget they’re working.

For most students, any exhilaration melts when test time nears.

“Assessment is inherently about power,” said the University of Wisconsin’s Kim. “Assessment is inherently about evidence and rules.”

By contrast, the new kinds of assessments empower students to challenge and question rules. In one proposed scenario, students in the PISA creativity test are asked to build a paper airplane, then come up with ideas to improve it.

In another, students design a “bicycle of the future,” suggesting three original improvements over standard bikes. Then they’re asked to tweak the design of a proposed anti-theft camera mounted on the bike. Finally, since the future bicycle is automatically powered, they must suggest “an original way to reuse or repurpose” the pedals.

“The idea should be original,” the test says, “in the sense that not many students would think of it.”

Kim has spent the past few years developing playful assessments for the classroom, originally with teachers, teacher trainees and game designers at MIT. Where Shute, her mentor at Florida State University, called it “stealth assessment,” Kim prefers the term “playful assessment.”

‘It’s a mind shift’

Kim has lately been testing something she calls the Assessment Party Game, a free, printable card game for teachers that Kim describes as “Charades meets Telephone” to teach the process of drawing conclusions from a chain of evidence.

In the game, players take on one of three roles: Performer, Observer or Interpreter. They can only see one of the other two players, and gameplay proceeds as the performer silently acts out, in three movements or less, what’s on a card. The observer takes notes on what she sees and determines how to tell the interpreter what she saw.

Like many in the field, Kim said a big roadblock to more playful tests is that so many school systems use assessments for teacher evaluations. “At the end of the day, we are obsessed with the idea that ‘Assessment is score: score about performance and proficiency.’”

Meanwhile, for most educators, play “is not something that is productive,” she said. “So for teachers to kind of switch their mindset in terms of, ‘Assessment can be fun, and this is an assessment,’ it’s a mind shift.”