In a rare public warning last spring, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy cautioned that social media presents “a profound risk of harm” to students’ mental health. To psychiatrist Laura Erickson-Schroth, technology’s ill effects on student well-being are clearly seen in the data, namely through a decade-long surge in youth suicides.

“As human beings we need social support, we need reassurance, and algorithms now are taking advantage of those needs and keeping us online and engaged with content even when it doesn’t feel good,” Erickson-Schroth said in an interview with The 74.

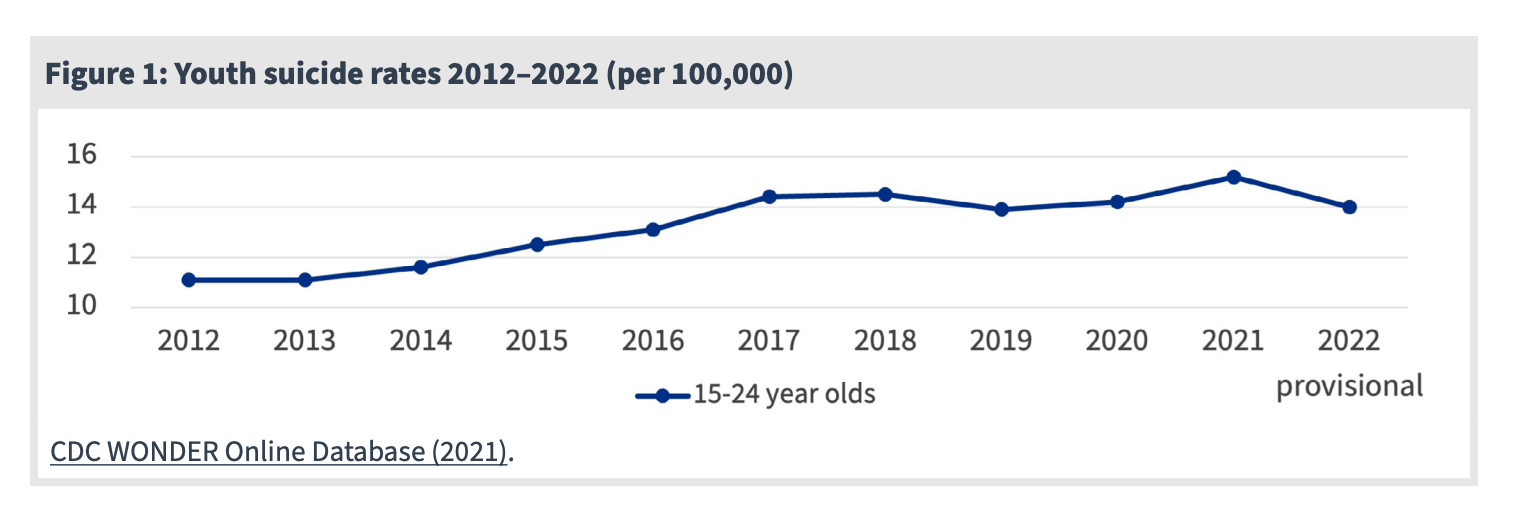

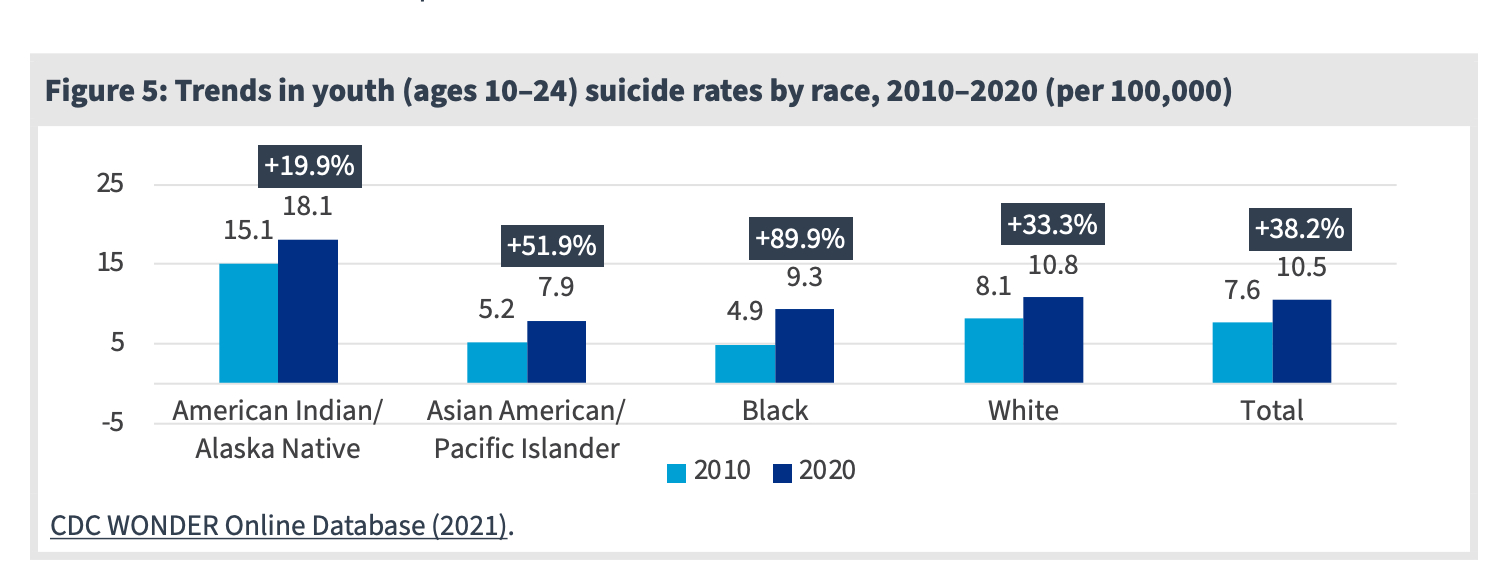

Youth suicide rates have escalated over the last decade, making it the second leading cause of death among teens and young adults. But suicide rates are starkly different among different populations, a reality brought into full view in a new report by the JED Foundation, a nonprofit focused on youth suicide prevention. And the harms of social media — the subject of a bipartisan push to regulate tech company algorithms and a bevy of lawsuits filed by school districts and states — is just one piece of the crisis.

But Erickson-Schroth, the JED Foundation’s chief medical officer, has observed one promising trend: Schools are more interested than ever, she said, in addressing students’ mental health needs.

The 74 caught up with Erickson-Schroth, whose work places a particular emphasis on LGTBQ+ mental health, to gain insight into the factors driving the youth suicide crisis, the conditions that put some groups of students at heightened risk and strategies that educators and policymakers can use to keep kids safe.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Among all youth, what are the primary factors that you see having contributed to the increase in the youth suicide rate over the last decade?

The COVID pandemic certainly played a role. Globally, rates of childhood depression and anxiety doubled during the pandemic. In my own practice, working with LGBTQ+ young people, I could see how the pandemic was affecting them. Many young people were becoming more anxious because of the social isolation and having trouble reengaging in social situations. Many of them missed important milestones like graduation, many young people lost people in their lives.

But I don’t think it’s the whole story. Youth mental health issues and suicide rates have been increasing for the last decade at least and the COVID pandemic doesn’t explain that.

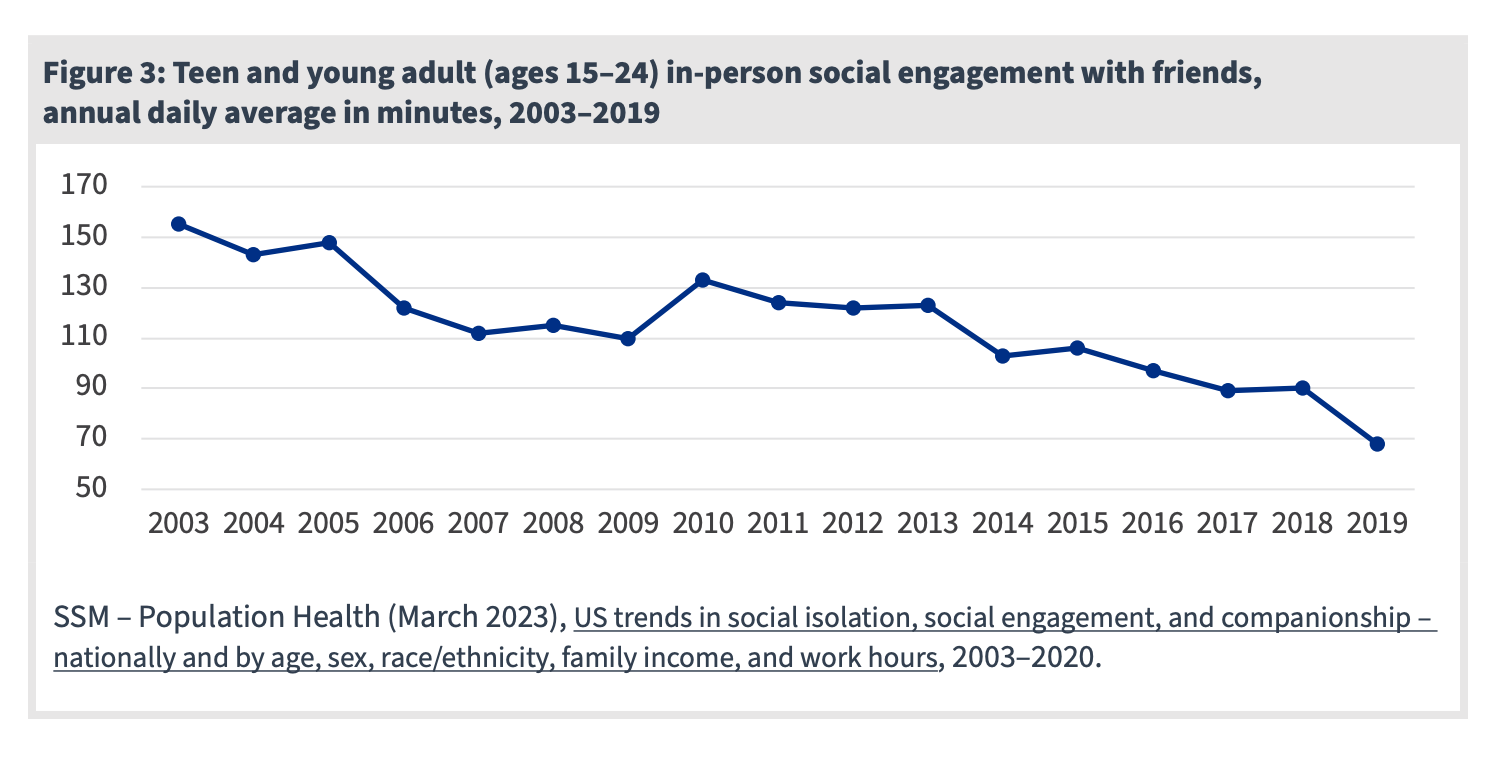

I think one of the biggest drivers is this increasing digital connection, when the internet met the phone, and we can see kind of around when that happened. If you look at studies of what percentage of Americans had smartphones at different times, in 2011 around 35% of people [had them] and now we’re up to about 85%. So almost everyone in the United States has a computer in their pocket.

That’s really different than the worlds that we grew up in in prior generations. There are a lot of positives and negatives to that. There are positives in building community and connections, especially for young people who have a hard time finding that in person.

But also it’s changed their lives completely in some negative ways. We’re constantly exposed to news, some of it really difficult news: wars around the world, climate change, racial violence, anti-LGBTQ legislation, those kinds of things. There’s cyberbullying, there are all of these chances for social comparisons, there’s this hijacking of reward systems.

As human beings we need social support, we need reassurance, and algorithms now are taking advantage of those needs and keeping us online and engaged with content even when it doesn’t feel good.

So all of that is adding up to a really different world that young people are living in where they’re increasingly lonely and disconnected socially.

Let’s turn to the pandemic. The data show that youth suicides reached a high in 2021 and leveled off a bit in 2022. What does this tell us about the pandemic’s effects on the youth suicide rate and how has the situation changed now that we’re no longer in lockdown?

It’s important to say that youth suicide rates have been increasing for a long time, long before the pandemic.

So we did see youth suicide rates rise during the pandemic. There was a study that looked at the second half of 2020, and there was a higher than expected rate of suicide for young people. It was particularly (true) among some groups, and that’s including Black youth. That likely had to deal with specific events that were occurring during the pandemic within those communities.

Black youth disproportionately lost members of their families and communities to COVID. The pandemic also coincided with these highly publicized incidents of racial violence. So, the pandemic really did have an effect on young people, but the pandemic isn’t the whole story.

If we’re talking about the increase from 2020 to ’21 and then the decrease from 2021 to 2022, yes, based on provisional CDC data we do see that there was an 18% drop in suicides for young people 10 to 24 and then a 9% drop for young people 15 to 24. The pandemic might have added to the numbers for 2021 and coming out of the pandemic might have improved those numbers.

But there were a lot of other factors that were contributing. I think one is that we’re paying more attention to mental health than we were in the past. We can see it in the numbers. Large donors gave more money towards mental health in 2022 than in any other year over the past decade.

At JED, we work with schools and we’re seeing more schools interested in making mental health a priority than we’ve ever seen before.

LGBTQ+ students have long experienced higher suicide rates than their straight and cisgender peers. What do the data show about the current political climate’s effects on their well-being and suicide risk?

There’s good research coming out of The Trevor Project. They do a survey every year that looks at LGBTQ+ young people’s experiences and one of the questions that they always ask is about how the political climate is affecting them. Based on their data, it looks like it’s affecting them quite a bit.

Young people who are hearing about anti-LGBTQ+ legislation or movements against their rights are having a more difficult time with their mental health, which makes sense. It’s important that, in our conversations about this, we make sure that people know it’s not about someone’s gender or someone’s sexuality. That’s not the reason that they’re having mental health issues. It’s about the way that our society reacts to young people who are different.

Black youth have experienced the fastest increase in suicide rates, with that rate nearly doubling in just the last decade. What do the data tell us about what might be at play here within the last decade in particular?

It’s always been really hard to be a Black young person in America, so what makes the recent decade different? I think what makes it different is, again, this constant digital connection.

The water that you swim in is this digital world and you have to spend time in this world because it gives you so many positives. It connects youth of color to other youth of color, who may be in other areas, so they can seek out community. It helps them connect with adults who are going to be supportive of them. But it also involves interacting with racist comments online, it involves seeing these really highly publicized incidents of racial violence. Young people are watching those videos and seeing what’s happening. They’re seeing movements for change, but they’re also seeing pushes back against those.

I’m curious about the rural-urban divide. Young people in rural areas are far more likely than their urban counterparts to die by suicide. What particular risk factors do rural teens face and what prevention methods might work best for them in particular?

I think young people in rural areas are in a unique position right now. There are a lot of positive benefits to living in rural areas. Young people getting out in nature and having close social ties. But at the same time, rural communities can be places where young people have less access to some of the things that they need. If they are in a particular group, there might not be as many people like them in that area.

It’s hard to connect to providers if you’re looking for mental health support because rural communities have lower rates of insurance and they have provider shortages. There’s also a lot of stigma around mental health in rural areas and it depends on the area, of course, from one place to another.

A really important one to talk about is access to firearms. It’s really common for young people in rural areas to have access to firearms. In rural areas, young people are twice as likely to die by suicide as those in larger metro areas. And they have easier access to firearms.

We have a lot of work to do in terms of expanding access to mental health care and making sure that young people can access mental health care in school. I was on a panel with a middle school and a high school principal and both of them were in rural areas.

And one of the things that they talked about was that young people in rural areas may not want to seek out mental health help from a clinic or a hospital because that may put them at risk of being identified as someone who’s getting mental health care. If you park your car outside of a clinic in a rural area, everyone else in your community knows what you’re doing. If you get mental health help in school from a school counselor, that’s just a regular part of the day that lots of young people engage with.

What immediate, actionable steps can parents and educators take to help prevent this problem from getting worse?

We can talk about immediately actionable things that we know are going to make a difference in the short term and then we can talk about longer-term solutions. In the short term, one of those things is, you know, how are we going to approach firearms?

More than half of young people who die by suicide use firearms and we know that firearms are readily accessible to many young people in their homes: 4.6 million children live in homes with at least one loaded, unlocked firearm.

How do we approach that? That’s through community work, that’s through making sure that gun owner groups, gun retailers and families are aware of the risks, that young people are turning to firearms when they’re thinking about suicide. Suicidal crises are often shortlived. Many people who attempt suicide, there’s very little time between when they first think about that suicide attempt and when they act upon it, so if we can reduce their access to lethal means in that moment, we can get them through the crisis and make sure that they have the support that they need, that they’re safe, that they have someone that they can talk to.

So that’s one of the clearest actions we can take.

How about policymakers? What key policy changes would you like to see, that you believe would have the largest impact on reducing young people’s’ risk for suicide? There are a lot of ongoing legislative efforts to limit children’s access to social media as a way to improve their mental health.

It’s really, really important that legislators and the government are involved in this issue. Number one, we have to establish a minimum set of safety standards for young people online. We have to have a regulatory commission that oversees that, we have to make sure that we have regulations for companies so that they don’t have to govern themselves.

Those kinds of things would include mandating that they collaborate with technology companies and independent research teams coming together to make sure that people outside of the companies are looking at the data ensuring that the algorithms are not negatively affecting young people’s mental health.

I think we have to take on advertising to young people. You know, what type of advertising is permitted at what ages, what the delivery looks like. We have to require that social media companies build in experts like psychologists to advocate for young people’s well-being and know what’s going on in the algorithms.

We have to make sure that we can accurately detect age, when young people are using these platforms. Those are all things that the government should be regulating.

There are things social media companies can do, too. They should be aggressively moderating harmful content. They should be making their data available to researchers and being transparent about their algorithms, they should be building in ways for young people to control their experiences online to be able to choose the kinds of things that they’re going to see.