The number of California school superintendents leaving their jobs is climbing, despite increased salaries and benefits. Some have reached retirement age or are moving to less stressful jobs. Some are being pushed out by newly elected school board majorities. A new crop of less experienced district leaders is taking their place.

Superintendent turnover in California grew from 11.7% after the 2019-20 school year, to 20.9% after the 2020-21 school year. Just over 18% left after the 2021-22 school year, said Rachel S. White, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who runs a research lab that collects data about school superintendents.

Turnover is particularly high this year because many superintendents who stuck it out during pandemic school closures, and the tumultuous years since, have had enough, White said.

“This year, before the 2023 school year, I think people finally broke,” she said.

Chris Evans, 52, decided to step down as superintendent of Natomas Unified in Sacramento at the end of last school year. He stayed on to help the new superintendent transition.

“The job was always hard to begin with, and it’s become infinitely harder,” said Evans, who led the district for 11 years.

“There are a number of folks in their 50s and 60s who are saying they are done,” he said.

Superintendents’ jobs changed dramatically after the pandemic closed schools in March 2020. Instead of focusing on academics, strategic planning, school finances and community relations, superintendents were charged with navigating pandemic mandates and negotiating these changes with district unions. Superintendents also were tasked with ensuring there were enough computers and connectivity for students and staff to support virtual learning, all while dealing with parents who were angry their children were not in school.

The reopening of schools did little to turn down the heat at school board meetings, which were politicized over issues such as the teaching of critical race theory and its tenets of systemic racism, and LGBTQ+ topics. School superintendents often found themselves the focus of community and parental ire — so much that some school districts paid for security for their superintendent.

Gregory Franklin, the former superintendent of Tustin Unified School District in Orange County, said he has never been threatened, but he knows other superintendents who have.

“I can’t ever remember hearing of a superintendent that had gotten a death threat before,” said Franklin, who left Tustin Unified at the end of 2021 for another job. “Now, I know personally four or five.

“It’s just kind of shocking. So, I think, all of that being said, that when other possibilities present themselves, people are taking them.”

The superintendent turnover problem is not California’s alone, according to the Superintendent Research Project. Nearly half of the country’s 500 largest school districts have changed leadership or are undergoing leadership changes since the pandemic began in March 2020. The study compared the two years before the pandemic to the first two years of the pandemic and found a 46% increase in superintendent turnover nationally.

“What we are seeing is that the challenges are greater than ever before and the political environment is creating great instability in the institution, which is resulting in shorter tenure for superintendents,” said Dennis Smith, managing search partner for Leadership Associates, a recruitment agency that does many of the superintendent searches in California.

California school districts searching for superintendents include Sacramento City Unified, Eureka City Schools, Palm Springs Unified, Eastside Union, Pasadena Unified, Pajaro Valley Unified, Pacific Grove Unified, Culver City Unified, Newman-Crows Landing Unified, Solana Beach School District, Culver City Unified, Dixon Unified, Millbrae Elementary, Woodlake Unified, Hillsborough City, Merced City, Black Oak Mine Unified, North Monterey Unified and Dos Palos-Oro Loma Joint Unified.

The California School Boards Association projected a superintendent shortage five years ago, said Susan Heredia, CSBA past president. It began as baby boomers started to retire, she said.

In the 15 months since Brett McFadden began work as a deputy superintendent at the Monterey County Office of Education, a quarter of the county’s 24 school districts have changed superintendents, he said. McFadden was the Nevada Joint Union High School District superintendent until last school year.

“If you look at the last 100 superintendents that had to leave their positions or their districts, you would be very hard-pressed to find any one of them that left because of test scores or left because of educational issues,” McFadden said.

“They leave because of local politics, board relations, labor relations, a facility bond matter or a budget thing.”

McFadden calls the COVID-19 pandemic the kindling that ignited the rise in single-issue adult-driven disputes, like those around masking and vaccinations, at school board meetings.

Demand is so high for superintendents that McFadden is already getting calls from search firms hoping to entice him to apply for jobs.

“You know the paint on the door isn’t even dry yet with my name on it,” he said. “These search firms are now just aggressively looking for candidates.”

Of the 30 candidates that apply for each candidate search, maybe eight to 10 meet the district’s qualifications, Evans said. Of those, there are only maybe three or four that could potentially be hired for the job, he said.

The high demand is driving up salaries and benefits packages, with total compensation surpassing the $500,000 mark in some cases.

Another factor pushing superintendents out the door is board members elected with the promise of firing the incumbent. The election of school board members who are determined to make significant changes in school districts has resulted in the firing of an unprecedented number of superintendents since the pandemic began in 2020, Smith said.

The school board meetings, broadcast live, have been watched throughout the state — especially by other superintendents.

McFadden remembers watching Pajaro Valley Unified school board meetings in 2021 when the board fired Superintendent Michelle Rodriguez without notice and then reinstated her days later after a public uproar. Rodriguez left to lead the Stockton Unified School District this year.

“You’d expect this in a Spanish novella or something, but you don’t expect it in your neighboring district,” he said.

Superintendents are watching these meetings and paying more attention than ever to whether they fit well with the community of the district before they apply for a job, said White, of the University of Tennessee.

“I think it’s just a heightened awareness right now,” White said. “Especially if I’m going to pick up and move my entire family and start a position in a new place. I don’t want to be fired in two years.”

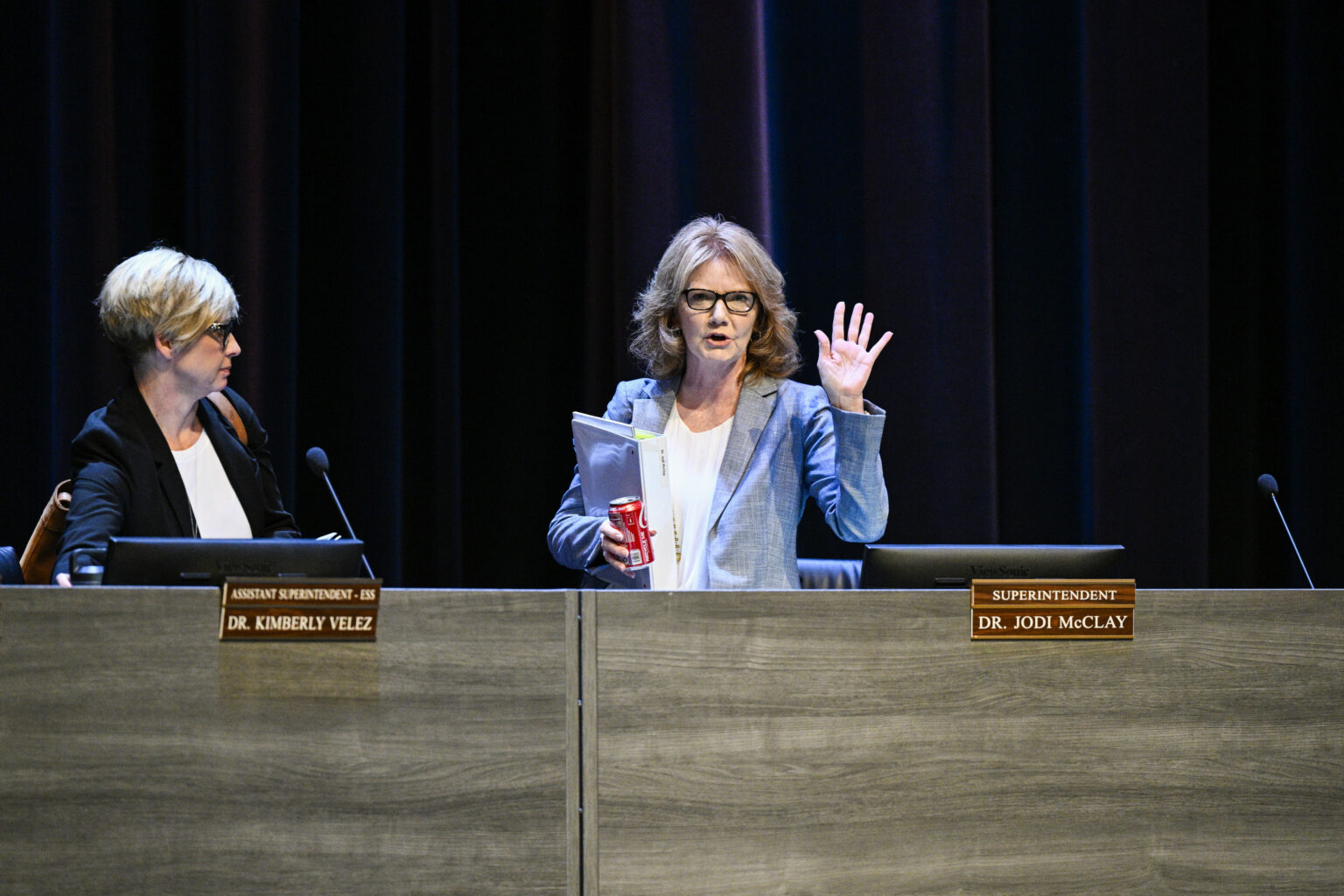

Temecula Valley Unified has been a hotbed of controversy since a trio of conservative trustees took control of the board a year ago. The board fired Superintendent Jodi McClay in June and banned the teaching of critical race theory, passed a parental policy requiring staff to notify parents if students are transgender and removed social studies material because it included a section on LGBTQ+ rights activist Harvey Milk.

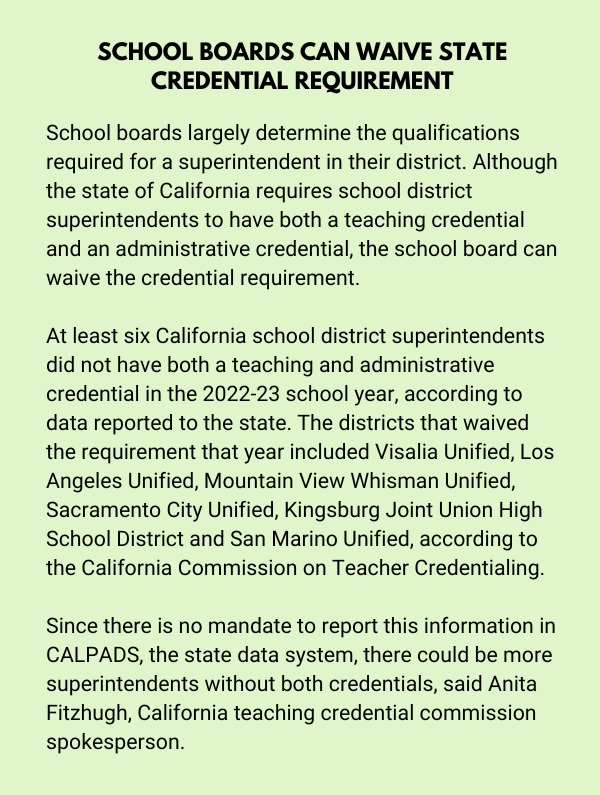

Although the search for a candidate ended on Nov. 13 with the hiring of Gary Woods, a former Beverly Hills Unified superintendent, the search firm indicated to one board member that there were fewer candidates than in the past. Quite a few candidates did not meet the requirements outlined by the district in a job description and some weren’t even from the education field, board member Allison Barclay told EdSource in early November.

“I would assume that if you’re looking for a position anywhere, any company, any school district, you’re really going to look at what the situation is you’re walking into financially, culture-wise, all of those things,” Barclay said. “And so, having a school district that is making national news is probably not appealing to as many people as might be attracted to it when it wasn’t making national news and was just simply known as an award-winning school district. So, I can’t imagine that that’s been helpful.”

State legislators responded to the spate of firings by passing a bill creating a cooling-off period, prohibiting school boards from firing a superintendent or assistant superintendent within 30 days of new board members being seated or recalled.

The law also prevents school boards from firing school leaders at special or emergency board meetings, which require only 24 hours’ notice, instead of at a regular meeting, which requires the public to be informed of a meeting at least 72 hours in advance. The bill was signed by the governor in October.

“People are recognizing it’s just not healthy for an organization to go through these flip-flops where you might have a 3-2 majority that keeps a school or a superintendent, then have an election where the 3-2 flips and then the superintendent is looking for a job,” Franklin said.

Assistant or deputy superintendents in larger districts are moving into the lead role in smaller districts, or superintendents in smaller districts are taking the opportunity to move to more lucrative jobs in larger districts. Newer, younger superintendents are becoming more common, Smith said.

To meet their administrative needs, many districts are also grooming their own talent, said Molly Schwarzhoff of Ray and Associates, a national education search firm.

‘I’m seeing different, perhaps less-seasoned individuals coming into the roles,” McFadden said. “That doesn’t mean they are less talented or more talented.”

To help new superintendents prepare for their new role, the Association of California School Administrators offers a new superintendents seminar series, a superintendents academy and a new superintendents workshop before its annual Superintendents Symposium.

The 2023 Voice of the Superintendent Survey, conducted by education consulting firm EAB, recommends that school boards find ways to help superintendents feel successful in their role and allow them time to connect with students and collaborate with peers to staunch turnover. Superintendents surveyed for the report overwhelmingly said they need help navigating challenging conversations with the community.

Superintendents report directly to the school board, something first-time superintendents have never done before, said James Finkelstein, professor emeritus of public policy at George Mason University in Virginia. The new superintendent now has multiple bosses, often with divergent interests. They also have to deal directly with parents and external interest groups.

“No amount of academic training or a certificate can prepare someone for this trial by fire,” Finkelstein said. “The bottom line is that there is no substitute for experience. But the catch-22 is that the only way to get the experience is by doing the job. Every school district would like an experienced superintendent who has demonstrated success in their previous position. But finding those individuals is increasingly difficult, especially given the dramatic turnover since COVID.”