After 16 months in immigration detention facilities in California and Texas, Jose Ruben Hernandez Gomez returned to his family home in Lodi in April, walking with a cane and saying he suffers from neurological problems and persistent nightmares.

The 33-year old Mexican-born man — who from toddler age has been a permanent legal resident of California — has reported enduring abuse, unsanitary conditions and threats of force-feeding before his release from immigration detention in April.

“I have nightmares of being dragged … that they are going to force-feed me. Then it wakes me up and I’m sweating,” he said during an interview at the home he grew up in. “It’s not an easy thing to process.”

This week attorneys helped him file an administrative tort complaint, a precursor to a potential lawsuit, against Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the federal agency overseeing immigrant detention.

His complaint seeks at least $1 million in personal injury damages.

It states that in March, while he and other detainees were staging a hunger strike to protest conditions at the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Center in Bakersfield, agents from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “violently dragged” him and several others and transported them to an immigration detention facility in Texas where he was shackled and a doctor threatened to seek a court order to insert a tube down his nose to his stomach to force-feed him.

Afraid, Hernandez Gomez agreed to end his hunger strike, which had gone 21 days, the complaint said. He suffered serious medical consequences anyway, his complaint says, after immigration agents made him immediately eat solid food and initially delayed medical treatment when he fell ill.

His complaint follows a class-action lawsuit he and eight other detainees filed in 2022 alleging forced labor by GEO Group, a corporation operating immigration detention facilities for the federal government. Also several Congress members from California have demanded an investigation or closure of the facilities.

“While I keenly understand challenges with ongoing litigation and the separation of powers, there is no excuse for the extremely limited replies and, at times, unresponsiveness from ICE,” said Zoe Lofgren, chair of the California Democratic Congressional Delegation.

“Members of Congress need more information about these serious matters occurring in our state. Relatedly, I reiterate my call for the closure of privately-owned ICE facilities today, including these two detention centers, because they too often have abusive conditions and are a rip-off to taxpayers.”

According to American Civil Liberties Union Northern California’s database, the federal contract to operate Mesa Verde in Bakersfield and Golden State Annex in McFarland is worth more than $1.5 billion over 15 years, or $105.4 million per year. The payment is for 560 beds regardless of the actual population count.

Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2019 signed a bill banning private prisons and immigration detention facilities from operating in the state, but the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined the new law was unconstitutional, saying “California cannot exert this level of control over the federal government’s detention operations.”

ICE officials did not answer questions from CalMatters, and GEO Group officials referred questions about the allegations to ICE officials. A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, provided a statement about the agency’s grievance process but did not answer other questions by deadline.

“The agency takes allegations of misconduct very seriously,” said Leticia Zamarripa, a public affairs officer for Homeland Security. “Personnel are held to the highest standards of professional and ethical behavior, and when a complaint is received, it is investigated thoroughly to determine veracity and ensure comprehensive standards are strictly maintained and enforced.”

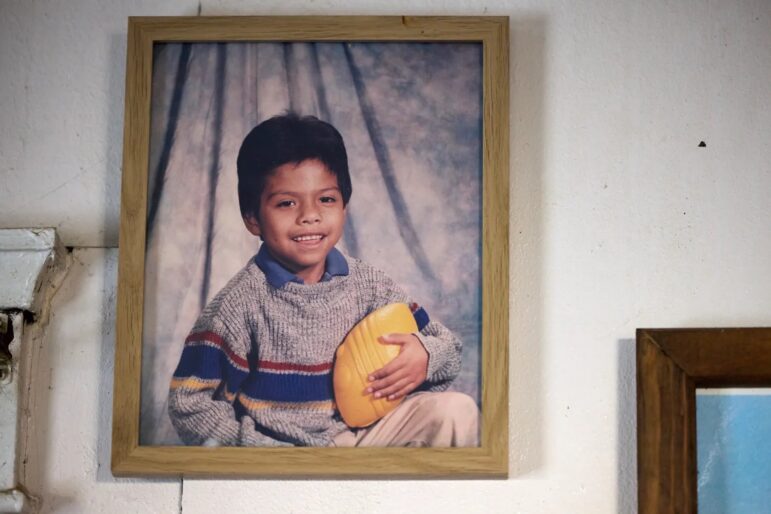

Recently, with the help of a metal cane, Hernandez Gomez walked around his living room, pointing to family photographs. But after a couple of minutes, he sat down and apologized for having to take a break.

“I am still surrounded by these feelings,” he said, “a combination of a whole lot: not being able to perform the way I used to perform, everything I used to enjoy and now I don’t.”

His family emigrated from Guanajuato, in central Mexico. As a teen Hernandez Gomez attended Lodi High in San Joaquin County, where he planned to become an electrician. But some arrests followed, he said, and he was convicted of assault and imprisoned at age 27.

Hernandez Gomez said he made better choices while incarcerated. He volunteered in a fire fighting camp program and participated in a self-help group and vocational classes, which helped shave two years off his six-year sentence. He was released in November 2021.

But he couldn’t go home. He was transferred to federal custody to await legal proceedings that could eventually deport him. He was placed in removal proceedings because of his criminal history and is fighting to stay in the United States.

He was detained at Golden State Annex in McFarland for two months, then Mesa Verde for more than a year. He said the place was infested with mold, water beetles and cockroaches, and the inmates drank rust-colored water from the faucets.

The ACLU NorCal database tallied the complaints detainees filed with ICE and shared with the ACLU. From January through October there were nearly 400 complaints and more than half were about living conditions and mistreatment. The ACLU’s foundation has sued ICE for information on complaints in California facilities.

Last February dozens of the detainees started hunger strikes to protest conditions, Hernandez Gomez among them. He said GEO Group and ICE officers retaliated against the hunger strikers.

“We were placed in solitary confinement,” he said. “We were threatened with being transferred to a different state.”

The complaint says, “On March 7, 2023, at about 6:00 a.m., multiple GEO officers dressed in riot gear entered Mr. Hernandez Gomez’s dorm. They disconnected the dorm’s phones so detained individuals could not call their attorneys or family members. They forcibly removed one of Mr. Hernandez Gomez’s dormmates from the dorm. A short time later, ICE officers dressed in military gear, holding batons, pepper spray, and what looked like automatic rifles, entered the dorm. They ordered Mr. Hernandez Gomez and other detained individuals to get on the floor. The officers did not state the reason for their orders. Instead, without notice or explanation, officers zeroed in on Mr. Hernandez Gomez and surrounded him. He asked to speak with his immigration attorney, but his plea went unanswered.”

The complaint said officers “threw Mr. Hernandez Gomez on the ground, causing him to strike his shoulder and chest against the ground.” One officer said, “Either you are going to walk, or we are going to drag you,” according to the complaint.

Officers cuffed and shackled him and eventually put him in a van with several other detainees, ultimately driving “many hours” to a private airstrip. Despite Hernandez Gomez requesting to go to a hospital because he felt dizzy, according to his complaint, he was placed on a chartered plane that later landed in Texas.

ICE has four pages of written standards for handling detainees on hunger strike, stating “if medically necessary, the detainee may be transferred to a community hospital or a detention facility appropriately equipped for treatment;” there’s no mention of transferring detainees to an ICE facility out of state.

Before boarding the plane, Hernandez Gomez said in the complaint that he endured a sexually abusive pat-down search that included his inner thigh, buttocks, and genitals.

“Nobody should be touching anybody in any place at any given time, no matter how long, no matter if it’s a millisecond,” he told CalMatters.

The detainees were driven to ICE’s El Paso Service Processing Center, where the complaint says a Dr. Iglesias informed them that she could seek a court order to force-feed them.

Force-feeding involves inserting a tube into a patient’s nose, down their throat and esophagus, and into their stomach, then pouring liquid food through the tube. Sometimes it causes patients to gag, choke or vomit.

Force-feeding is legal but controversial. The American Medical Association has said force-feeding prisoners is unethical, while the World Medical Association recently called it torture. Some judges have said it could be done to keep patients alive.

In 2019 Dr. Michelle Iglesias, an ICE contract physician with a family practice in El Paso, testified in federal court that ICE requires force-feeding if hunger strikers endanger themselves. The judge granted a court order in that case. Iglesias oversaw multiple forced feedings, according to Texas Monthly.

CalMatters left phone messages at Iglesias’ family practice office and emailed her practice but got no response. In 2022, Homeland Security shared a video on social media featuring Iglesias describing her medical experience and motivations for working at Homeland Security.

Afraid of being force-fed and after being placed in solitary confinement, Hernandez Gomez informed health care staff he would break his 21-day hunger strike. But instead of honoring his request to start with vitamins and electrolytes, they gave him two cold cheeseburgers and fries, the complaint said.

Hernandez Gomez added, “When I consumed that, after 21 days, I just started feeling dizzy. That was the beginning of my second hell.”

Dizziness, disorientation are common symptoms of refeeding syndrome — “potentially fatal shifts in fluids and electrolytes that may occur in malnourished patients receiving artificial refeeding,” according to medical research.

Hernandez Gomez said he felt disoriented and his vision deteriorated so much he had to wear glasses, but he didn’t receive treatment for his symptoms.

On March 14, Hernandez Gomez was flown back to Mesa Verde. That day, he recalled, he continued experiencing headaches and dizziness, so the medical staff at Mesa Verde gave him a cane and a wheelchair. He was later treated at a hospital emergency room in Bakersfield where, for the first time, he was evaluated for refeeding syndrome, the complaint said.

The symptoms worsened, the complaint said. Hernandez Gomez was sent to another hospital and hospitalized for five days, with his waist, arms and legs shackled to a bed.

“I shed tears, because how are they getting away with all this? I am a human being, I shouldn’t be treated that way,” Hernandez Gomez said.

Weeks later a federal court ordered ICE to a bond hearing, where attorneys representing Hernandez Gomez submitted evidence of neglect and medical mistreatment. An immigration judge found Hernandez Gomez was not a danger to society and ordered his release with a $5,000 bond.

But on April 14, Hernandez Gomez didn’t walk out of Mesa Verde. He was wheeled out in a wheelchair. It was the first time he saw his father cry, he said.

“I am not free,” he said recently, “because I’m always having these flashbacks. At times, I cry myself to sleep. And even though it hurts, I don’t want others to go through that any longer.”