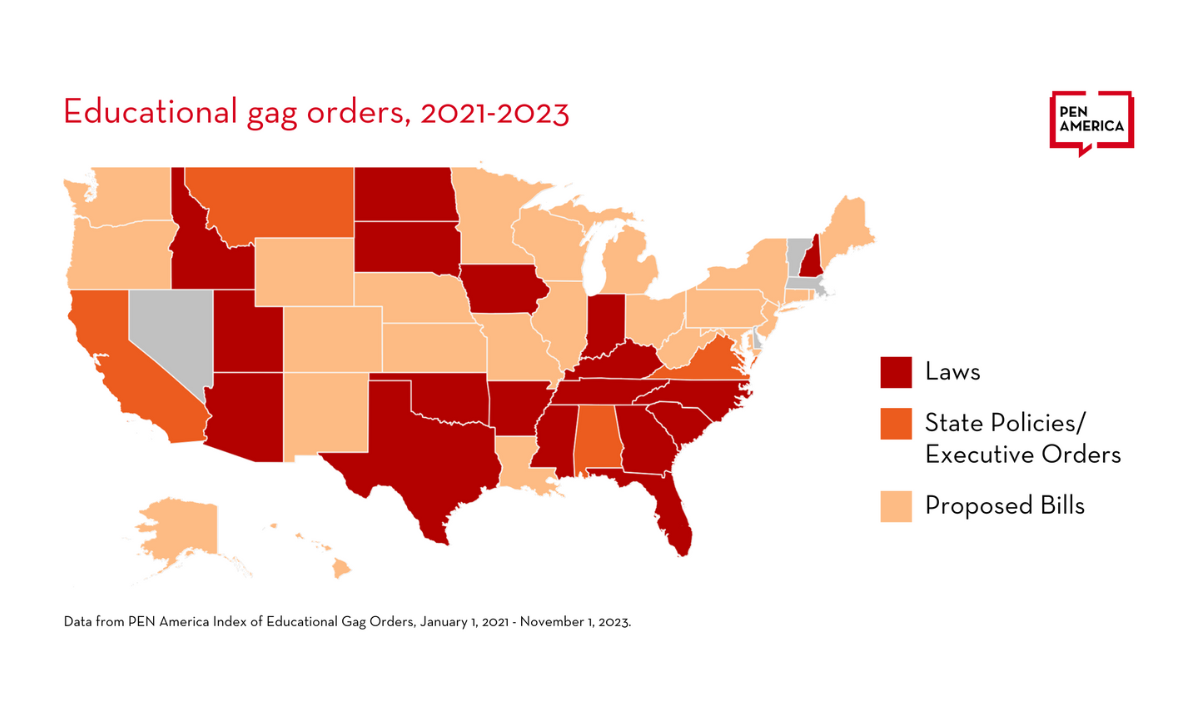

So far this year, 110 bills seeking to restrict discussion of race, U.S. history and LGBTQ people in schools and colleges have been introduced in state legislatures, and 10 became law, according to a new report from the free-speech watchdog group PEN America. Added to the 20 such bills passed in 2021 and 2022, and 10 executive orders and state agency mandates, there are now 40 legal restrictions on educator speech in 21 states.

PEN estimates 1.3 million K-12 teachers and 100,000 public college and university professors are now affected, as are millions of students.

The analysis traces how proponents of what PEN calls educational gag orders have adjusted their tactics over the last three years. The authors say this reveals both rising public opposition to the laws and efforts by the restrictions’ right-wing backers to steer around political flashpoints. As a result, they say, they expect more — and more draconian — bills in 2024.

“What we have seen this year is that the people who are advocating for these laws are not going to stop because the poll numbers are bad, they’re not going to stop because some parts of the laws have been struck down by the courts, they’re going to continue,” says Jeremy Young, program director of PEN’s Freedom to Learn initiative. “They’re going to continue to evolve these laws in more and more insidious ways.”

“This is an ongoing crisis,” he adds. “And it will continue until these laws are defeated in the courts or at the ballot box or in the legislature consistently.”

Backers of the measures argue that parents of K-12 students need more control over what their children are exposed to in school and that colleges should not foster discussion of “divisive concepts.” Teaching about race, history, gender and sexual minorities and other topics, they say, pressures students to adhere to an ideology and tramples the free speech rights of those who disagree.

“If we do not act now, I fear we will continue down the path of servitude to a woke agenda from which there may be no return,” Republican state Sen. Jerry Cirino argued in support of a 2023 Ohio bill, still under consideration, that would ban speech on a number of topics. “This bill isn’t even law yet, but it’s already served as an agent of change.”

How much of the broader public agrees and is comfortable imposing restrictions on educators varies greatly depending on the topics at issue, the age of the students in question and how the measures are framed, PEN’s analysis found.

The report traces the genesis of the movement to curtail instruction to former President Donald Trump’s September 2020 denunciation of “toxic propaganda,” including classroom materials based on “The 1619 Project,” The New York Times’s and journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones’s history of race in America. Three months later, the first state bill to curtail what teachers could say about race was introduced in Mississippi.

The vast majority of the speech-restricting measures introduced in 2021 and 2022 focused on stopping instruction involving race and history and “divisive concepts” in K-12 schools and colleges — often targeting both in the same piece of legislation. By contrast, in 2023, no bills simultaneously focused on the K-12 and university levels.

Thirty-nine of this year’s measures were aimed solely at shutting down discussion of LGBTQ people and topics in elementary and high schools. Most are modeled after the Florida law that critics refer to as the “Don’t Say Gay” act. The laws have been cited by people demanding book bans and in the elimination of anti-bullying efforts.

More bills are expected in 2024, and PEN believes some will go much further. This year, for the first time, some of the proposed measures took aim at individuals’ speech, the report notes, with an Oklahoma bill to prohibit students from disclosing their LGBTQ identity and one in Ohio that would mete out “disciplinary sanctions” for college students or faculty who violate the “intellectual diversity rights” of others by discussing topics such as “allyship, diversity, social justice, sustainability, systemic racism, gender identity, equity or inclusion.”

“So a dean who sends out an email cheering for the new sustainable roof on the environmental sciences building [would be] violating the law because he’s expressing an institutional position on sustainability,” says Young.

There are practical reasons why the legislation proposed in 2023 and predicted for next year — which in many cases use identical language, suggesting increased coordination across states

— will be harder to fight than the laws previously enacted, he says. Courts are likely to uphold college faculty free speech rights, but so far advocacy groups trying to overturn bans on LGBTQ topics have had a hard time meeting the legal threshold for proving plaintiffs have been harmed.

PEN’s researchers suggest public opinion may be one reason why backers of the bills have changed tactics and appear poised to do so again next year. Polls consistently show that Americans support teaching older students about race and oppose banning books about the topic. A 2022 survey by the American Public Media Research Lab and Pennsylvania State University found just 13 % of respondents believe state lawmakers should have a “great deal of influence” over classroom discussions of race or slavery.

Some of the same surveys, however, have found much lower support for exposing K-12 students to LGBTQ topics, a much higher partisan divide and disagreement over at what age, if any, such discussions are appropriate. A University of Southern California poll last year found that 80% of Democrats say high schoolers should learn about gay rights, sexual orientation, gender identity and trans rights, while fewer than 40% of Republicans agree. Only about 30% of Americans believe such instruction is appropriate for elementary pupils.

Republicans, he adds, are starting to make inroads with Black and Latino voters and as a result may be reluctant to continue to describe race as a divisive concept.

Polikff also agrees with PEN’s assertion that the bills’ authors changed the way they targeted speech at colleges and universities because public opinion data showed that attempts to curtail what professors may say — a centerpiece of many 2021 and 2022 bills — are wildly unpopular.

Recent bills propose dismantling faculty unions, senates and other internal groups that protect academic freedom — systems most people have never heard of. For example, a Florida law passed this year weakens faculty hiring and tenure rights and, by decreeing that course content “may not distort significant historical events or include a curriculum that teaches identity politics,” makes it virtually impossible for some classes and majors to be taught, critics say.

“This new breed of legislation is designed to kick the legs out from underneath university governance and autonomy,” the PEN report explains, “so that the next time the state moves to censor faculty, no one is in position to push back.”