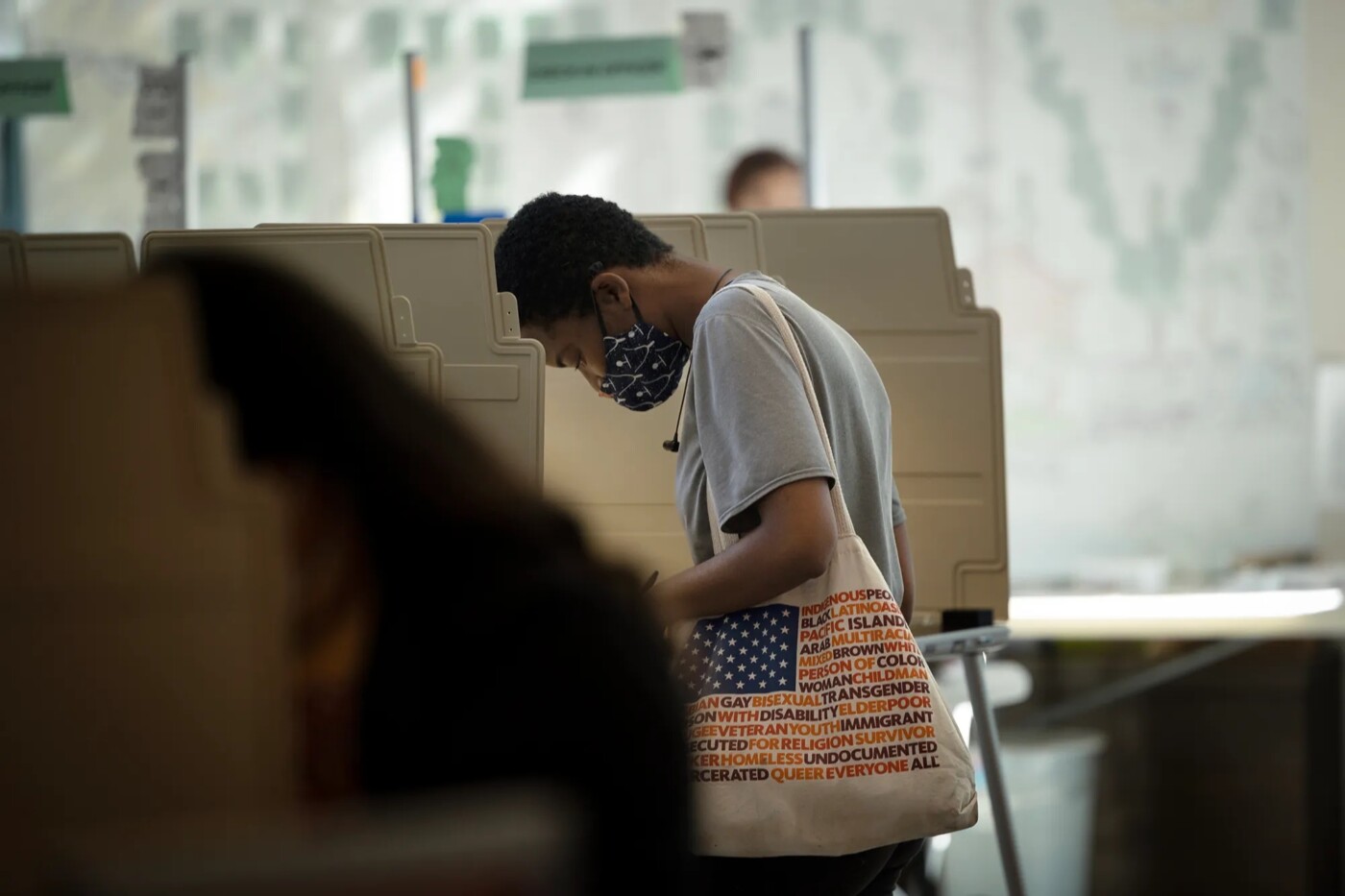

The 2020 presidential election produced some of the highest turnout of young voters and voters of color. Alex Lalama was among them.

A San Francisco State University student at the time, Lalama was one of many students becoming more politically involved, which Lalama attributes to the “era of Trumpism.” In fact, according to the Berkeley Institute for Young Americans, even though little is known about many of the factors influencing youth voter turnout, disapproval for Donald Trump was one that significantly correlated to voter turnout for people ages 18 to 39.

“Young people were coming out in the masses,” Lalama said. “I think young people like myself just really saw what we were up against.”

But since the 2020 election, voter registration rates for people 18 to 25 have begun to decline in the Bay Area, and there remains a significant gap in voter turnout for people of color compared to white voters.

Now, Lalama is the lead student organizer for San Francisco Rising, a grassroots political organization with a goal of getting young people registered to vote and informed on political issues.

There are more than 200 organizations in the Bay Area working to boost political engagement and voting among marginalized communities, according to a report from Bay Rising Action, a grassroots political organizing nonprofit. As the nation gears up for the 2024 Presidential Election, Lalama said there’s a big objective:

“Making sure that we don’t lose the vote of young people.”

All nine Bay Area counties saw a spike in voting registration for people ages 18 to 25 from 2019 to 2021, according to the California Secretary of State’s odd-year registration reports. That trend hasn’t held over the last two years, however.

San Mateo, Alameda and Solano counties saw the largest drops in registration rates from 2021 to 2023. Despite the decline, San Mateo sustains one of the highest registration rates at 73 percent, while Alameda and Solano have the lowest at 54 percent.

James Taylor is a political science professor at University of San Francisco with a focus on African American political history and ethnic politics. Taylor said the decline in voter registration among youth is in part due to Democrat and Republican parties wanting “to fight about sexuality and culture war” — not the policy issues the younger generation cares about. Lalama expressed the same concern.

“Young people are discouraged by the politics of the two parties,” Taylor said. “We don’t see [policymakers] fighting affirmatively for young people in terms of making this a better world and a better society.”

San Francisco Rising organizer Sana Sethi said it’s typical to see a drop off after a presidential election, but voter registration is expected to rise as the 2024 election gets closer.

“SF Rising does plan to continue to reach and register young people who are eligible to vote and remind them of the importance of registering and voting in all elections, not just presidential elections,” Sethi said.

To gauge the degree to which young voters felt politically engaged, Bay City News conducted an informal survey online and on college campuses, gathering more than 300 responses.

Students noted that issues like housing, gun policy, climate change and the economy were most important to them. Yet when it came to voting, many students said they still didn’t feel especially motivated to show up to the polls and felt uninformed on local politics.

Despite an increasingly diverse general population across the US, The Public Policy Institute of California found in 2023 that California’s likely voter demographic is disproportionately made up of older, white, affluent adults. Nonvoters were more likely to be younger, Latino and lower income. Taylor said youth and people of color are the two groups that have faced the brunt of voter suppression efforts that picked up in 2020 from Republican legislators across the nation.

Statewide, the share of African American likely voters was 6 percent in 2020, which matched African American representation in the state’s adult population overall, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. But Black communities have reduced in size. According to an analysis by Bay Area Equity Atlas, the Bay Area’s Black population decreased by 10 percent from 2000 to 2020, following a similar trend statewide. Taylor said Black residents like himself can feel “invisible” in their hometowns.

“Either nobody sees you, or you’re a criminal,” Taylor said.

Despite feelings of invisibility, discouragement and distrust of the political process, many people remain determined to galvanize participation in elections by youth and people of color.

Lucila Ortiz, political director for the Silicon Valley-based nonprofit Working Partnerships USA recalled growing up in San Jose an undocumented immigrant.

“Not being able to vote, I always felt really powerless,” Ortiz said.

She began organizing in high school and has been working with low propensity and immigrant voters ever since.

“That was my way of getting my voice out,” Ortiz said. “Making sure people who did have that right were able to exercise it.”

For Ortiz, guiding eligible voters through complicated ballot language, informing people of their rights to get time off from work and keeping them civically engaged year-round has been key in her work to fill the gaps in turnout.

Despite generally lagging registration rates, researchers predict that youth, especially Latinx young voters, will have a heavy influence on the outcome of the 2024 election. The US Latinx population is much younger than others, and a majority of Latino voters under 30 voted for the first time in either the 2020 or 2022 elections (56 percent), according to the Brookings Institution.

Meanwhile, Christine Chen, the executive director of APIAVote, said election outreach has historically overlooked Asian American and Pacific Islander communities, as shown in the organization’s 2022 voter survey. But it’s also the fastest growing population in the US.

According to APIAVote’s 2022 California voter survey, the number of eligible AAPI voters in the state grew by 36 percent from 2010 to 2020, while the state’s overall eligible voter population increased by 15 percent. Additionally, 18- to 29-year-olds make up 21 percent of the state’s AAPI citizen voting age population as of 2022.

In San Francisco, Tiffany Ng works as the civic engagement director for the Chinese Progressive Association to help boost turnout and political participation, among the city’s Chinese immigrant population as well as youth.

Ng and Chen said some of the biggest voting inhibitors they see within the Asian American community are language barriers and cultural differences, as people may be used to different types of government structures., including some that discourage participation.

“Here, you have a voice, you can be part of decision making, you can be part of choosing who represents you,” Ng said. “We work on breaking that stigma and barrier.”

Ng said two efforts that have helped improve participation have been language assistance and mail-in voting that have allowed people more time to think through their ballots.

“How good our public transit is, how much affordable housing is built — so much of our basic needs are funded and operationalized through the government,” Ng said. “Policies impact our material conditions and lives, so we want more people to be involved in the process instead of just allowing a subset of people, who may be more privileged, to be engaged.”

Discouraged by political climate, uniformed on local issues

At campuses like UC Berkeley, San Francisco State and Napa Valley College, a number of students felt that they didn’t have time to pay attention to politics.

These sentiments are echoed in research from Charlotte Hill, a professor at Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy. She found that youth are less informed about political processes and find greater difficulty balancing voting with other life tasks compared to other age groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s social and psychological ramifications may have exacerbated this. SF State’s Taylor said the younger generation is working to recover from their early adulthood years being disrupted by the pandemic.

“COVID erased two years of everybody’s life away practically,” Taylor said. “And now you’re trying to become civic minded to be able to be a committed voter.”

Another factor dampening enthusiasm for voting among young people is the sense that many politicians don’t really care about their constituents. They say the increased political divisiveness and polarization they’ve seen in their families and across the Internet have only discouraged them from participating.

UC Berkeley economics senior, Mohammad Al-Jebori, said he believes politicians care more about monetary gain than policies.

“All these powers just use politics to make it seem like they’re doing it for the people. But at the end of the day, it’s just agendas,” Al-Jebori said.

Al-Jebori voted in the 2020 election, but he couldn’t recall if he voted in the 2022 midterms, and he’s still unsure whether he’ll vote in 2024. He hasn’t been following the candidates closely and said that as he’s gotten older, he’s come to see that the “politics is for the people” idea is a misconception.

Another problem, Lalama said, is that campaigns often tokenize young voters, only putting resources toward them for a short period of time to help pass specific policies or get certain candidates elected. Beyond that, Lalama said young people are constantly told “they’re too radical, they’re too idealistic.” Lalama is seeing young people become discouraged from voting, having seen how little some candidates uphold promises on the issues youth care about.

“How do we empower them long term to actually feel like their ideas can be implemented?” Lalama asked.

In response to these concerns, organizers across the region are employing strategies for “transformative civic engagement” as Lalama put it — helping young people feel informed and politically involved year-round, not just during an election.

While Al-Jebori feels cynical about the power of voting, he acknowledged that low turnout ultimately allows more corruption to grow.

“The more divided we are, the more we fight within ourselves and the less likely we’ll be to ever get this country back,” Al-Jebori said. “Or not even back to where it was — it’s not like this country was great. We’re trying to make it amazing, something that it’s never been.”

Division is what has kept Santa Rosa Junior College student Jeomar Banda out of politics. He said he’s registered to vote, but hearing his family argue has deterred him from getting involved at all.

Survey respondents said they felt they lacked access to information on local issues. Most get the bulk of their news from social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, but those platforms are less likely to show current events at a local level — an obstacle to generating interest in local candidates.

Most of the students interviewed did not vote in the 2022 midterm election. While midterms historically receive lower turnout, young voter turnout nationally for the 2022 midterm was even lower than in the 2018 election, according to the Brookings Institution.

How one organizer empowers voters at an early age

One organizer racing to empower youth before cynicism deters them is Lukas Brekke-Miesner.

By 10 years old, he was knocking on doors gathering signatures to help pass city measures in Oakland.

Raised by two parents involved in local organizing, Brekke-Miesner now carries on that mission as the executive director of Oakland Kids First, a group mentoring and empowering high school students to get civically engaged.

“We’re an organization that believes building power is paramount, and voting is one lever, one tool to go about that,” Brekke-Miesner said. “But we also have generations of proof that our democratic process has not yielded results for a lot of oppressed communities.”

He said his goal is to help transform the system surrounding youth by giving them a platform to speak directly with local leaders about the issues that are important to them, so that future generations “don’t need to be as … resilient as current young people have to be in Oakland.”

“You’re trying to help young people navigate through really bleak terrain,” Brekke-Miesner said.

Brekke-Miesner said the majority of Oakland Unified School District students live in districts five, six and seven, whose demographics are predominantly Latinx and Black. Those districts also have the lowest voter turnout.

“Which in turn means that the majority of the [school] district has the least amount of representation,” Brekke-Miesner said.

By working directly in district schools, Brekke-Miesner is hoping to see that representation increase.

“Without doing that groundwork what you’ll see is a bunch of … 17-year-olds registered to vote, they’re predominantly white, they’re predominantly affluent, from the hills, predominantly attend private schools not even related to OUSD,” Brekke-Miesner said.

Brekke-Miesner says that one of the biggest challenges for organizers working with youth is the turnover rate of their audience.

Whether at the high school or college level, young people move around. When it comes to encouraging those students to get involved in their communities, it’s all the more difficult when their location changes every four years, sometimes more.

Now, Brekke-Miesner said he and other organizers are trying to develop longer-term organizing approaches — from organizing with the families of the students they work with to building alumni networks.

“I think we’ve just been shooting ourselves in the foot doing all this development and organizing work and then kids graduate,” Brekke-Miesner said. “There’s not a warm handoff to other organizations that are doing great work for a way for them to stay engaged.”

One barrier to staying involved locally that Brekke-Miesner has seen in Oakland is the gentrification of neighborhoods, which has pushed some young people out, making it harder for them to be engaged in extracurricular organizing or to stay in school at all.

“We have high school students that are commuting from Stockton and Vallejo to finish graduating,” Brekke-Miesner said. “Because of financial pressures, a lot of young people just have to get jobs, whether that means they’re not continuing school or whether it means they’re not as engaged. The financial constraints and the housing insecurity components are huge trends right now for our young folks.”

One strategy for keeping students involved after high school is implemented in Oakland Kids First’s affiliate program called Real Hard, which teaches youth leadership and local organizing at five Oakland high schools. Brekke-Miesner said all of those chapters are now being run by former high school students who went through Real Hard themselves.

“I think historically in some of the youth organizing fields, there’s a lot of folks that, you know, kind of parachute into a community that they don’t belong to,” Brekke-Miesner said. “White people are specifically guilty of this. So I think the cultivation of folks from the community that I’ve gotten to come up to be practitioners and leaders in those organizations is also something that we’ve really been pushing and I’m hoping will emerge as more of a trend.”

Brekke-Miesner and the students in Real Hard fought for a measure in Oakland that would allow 17-year-olds to vote in school board elections. The measure passed in 2020 and is currently in the process of being implemented by the 2024 election, enabling approximately 8,000 more citizens to vote in school board elections.

“Research shows that younger first-time voters are more likely to become lifelong voters,” Brekke-Miesner said.

But the work doesn’t stop with the measure. Brekke-Miesner said his organization will also be working to make sure that young voters are “as informed as possible.” That means getting students involved in local civic life, teaching political processes and empowering youth to hold their leaders accountable.

“Mobilization doesn’t just look like voting,” Brekke-Miesner said. “Is the work that we’re doing in between elections relevant to holding folks accountable? I think that is kind of representative of how we try to approach when we talk about voting and voter turnout with our young folks.”

To Lalama, young people are also likely to be motivated to vote after the Supreme Court decisions on affirmative action and student debt, along with anti-LGBTQ bills seen across the nation.

“I think young people, without a doubt, understand that with the rise of student debt, the climate crisis that we’re facing — there is so much at stake for younger generations, and they want to fight for them,” Lalama said.

As a Latinx voter, Lalama said voting can feel especially important when you come from a first-generation family or have family members who aren’t citizens.

“You’re not only voting for yourself, but you’re voting for your family,” Lalama said. “You’re voting for all of those in your community who can’t vote.”

Brekke-Meisner said it’s especially important to connect with students at Oakland’s public schools, many of whom are from marginalized communities. He said some have parents who cannot vote themselves, whether they’re undocumented, formerly incarcerated or struggle with language barriers, among other challenges. According to Taylor, one of the strongest voting predictors in political science is whether someone’s parents vote.

“To say that there are parts of our city that are ignored and divested is an understatement. And to say that the majority of our young folks that might win the power to vote come disproportionately from those communities, both statements I would say are true,” Brekke-Meisner said. “If we don’t have a calculated effort to engage those young people, then we’re not doing our job.”

Taylor encouraged the younger generation to consider multiple fronts for civic engagement. While voting is one avenue, he stressed the impact other platforms can have in a social movement — from one’s job to community service.

“I think a movement from young people that is coherent, that is effective, that is comprehensive, would be a breath of fresh air,” Taylor said.