Middle- and high-school students, who have the least time to catch up before they leave the K-12 system, may be suffering the most as schools emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, warns a new report released Wednesday. These students, researchers said, “deserve our urgent attention.”

The report, which relies largely on recent findings from outside research groups and the federal government, warns that on just about every indicator that matters — basic skills, college going, mental health and more — the pandemic has set older students back.

“Time is running out for these kids,” said Robin Lake, director of The Center on Reinventing Public Education, a research organization at Arizona State University. “Many have already exited the K-12 system, either by graduating or essentially disappearing on us. Too many kids still are missing — we don’t know if they’ve dropped out or where they’ve gone.”

Outside researchers who study these students said the fears are justified. In response, Lake and others are proposing a raft of reforms, including extending “gap years” to any high school graduates who need time to catch up — as well as a new commitment to reforming high school so it works for more students.

U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona acknowledged the slow pace of academic turnaround, calling it “appalling and unacceptable.”

“It’s like as a country we’ve normalized those gaps,” he said in separate remarks to reporters Tuesday,

Cardona spoke just before the department unveiled new efforts to spur pandemic recovery, including $50 million in competitive grants for literacy and higher expectations on districts to track and reverse chronic absenteeism. The department also released new data showing that roughly 187,000 tutors and mentors have signed up through its National Partnership for Student Success — bringing it closer to its goal of recruiting 250,000 adults to help students get back on track by 2025.

‘Insidious and hidden’

As of this fall, researchers said, about 13.5 million students in four high school graduating classes have been affected by the pandemic.

CRPE first issued its “State of the American Student” report in September 2022, saying pandemic school closures in 2020 and 2021 led to “unprecedented academic setbacks” for American students that made pre-existing inequalities and the nation’s youth mental health crisis worse.

A year later, CRPE says, students are still struggling in many areas. They point to record-low math and reading scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress for fourth- and eighth-grade students — in both grades, one in three can’t read at even the “basic” achievement level.

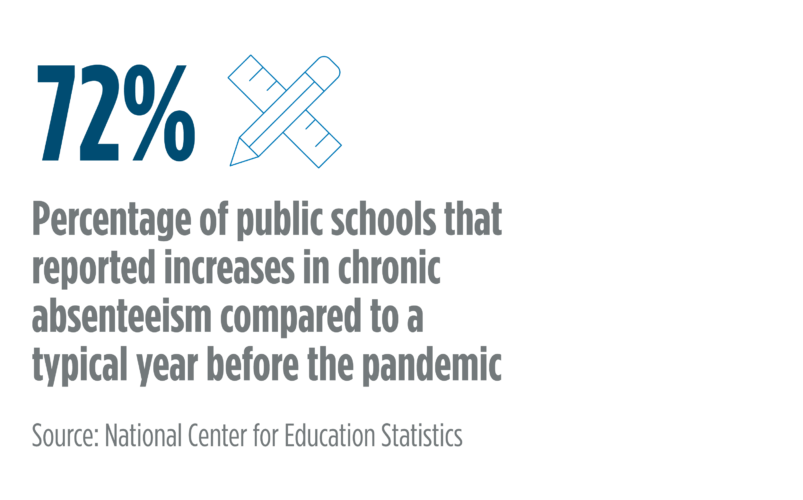

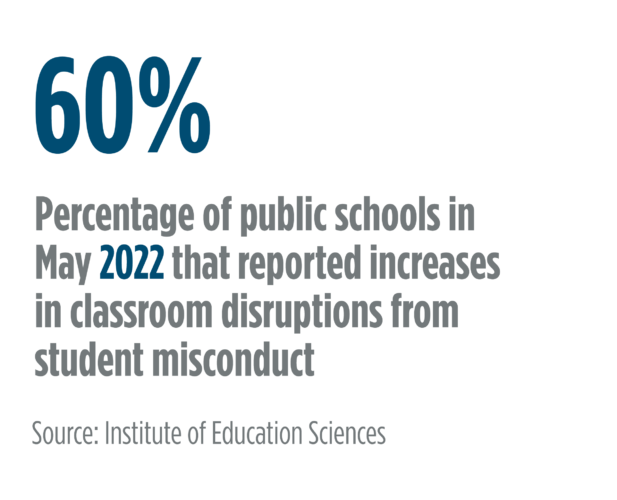

And 16 million students missed more than 10% of school days during the 2021-22 school year, twice as many as in previous years. More than eight in 10 public schools reported “stunted behavioral and social-emotional development” in students because of the pandemic, researchers note.

But they say schools should pay extra attention to older students, many of whom lost critical instruction time during the pandemic.

The pandemic, Lake said, “is continuing to derail learning throughout K-12. But what we came away with was that the derailment is looking a little bit more insidious and hidden, in some ways. That is true especially for older students.”

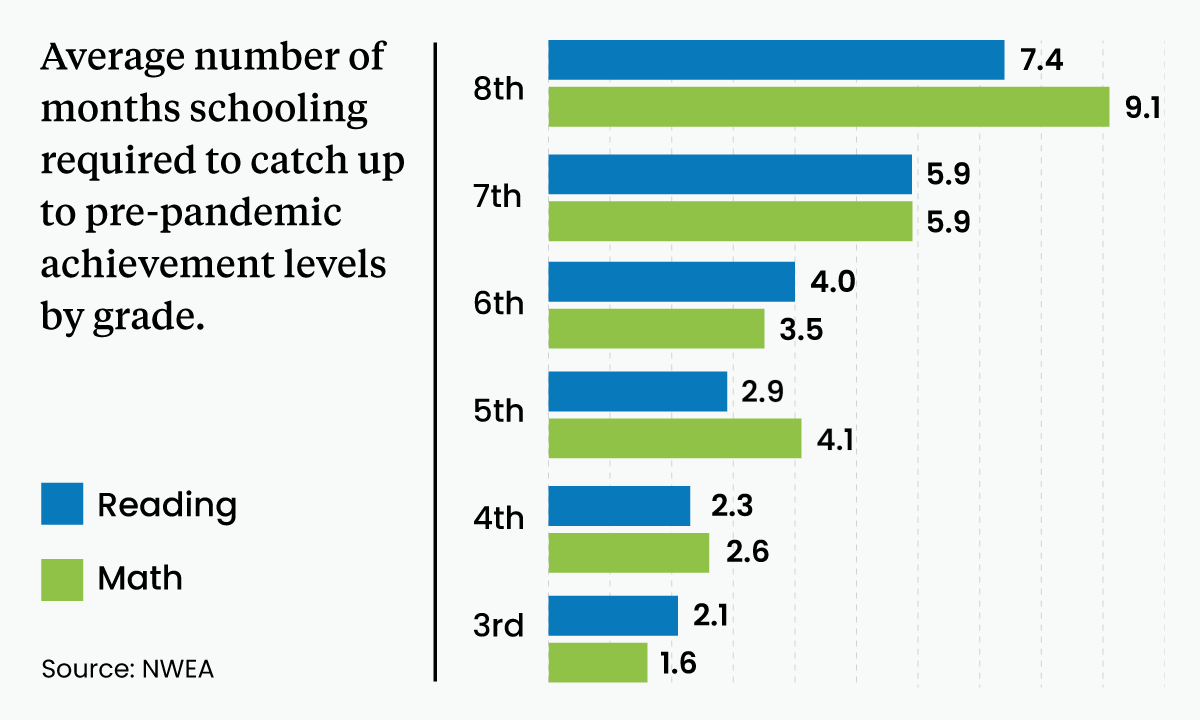

The average eighth grader, for instance, needs 7.4 months of schooling to catch up to pre-pandemic levels in reading, and 9.1 months of schooling in math, according to recent assessments.

Last year’s NAEP scores showed that 30% of eighth graders performed “below basic” in reading; 38% were below basic in math. At the same time, just 2% of students received high-quality tutoring at school, which Lake called “a massive missed opportunity.”

In a few places, researchers noted, the pandemic knocked older students off track, as in Washington state, where 14 percent of public high school students received at least one failing grade during the 2020-2021 school year.

Even college-bound high school students are underperforming: The average score on the ACT college admission test last year was 19.8, they noted, the lowest since 1991.

Researchers also noted that, overall, college going is down: Between 2019 and 2023, the U.S. higher education system lost an estimated 1.3 million students.

Speaking to reporters on Tuesday in advance of the report’s release, Lake said recent data on college are “extremely concerning.”

In the report, Lake noted several promising new models, including Colorado’s Homegrown Talent Initiative, designed to help rural districts create career-relevant learning experiences aligned to the needs and aspirations of local economies.

She also highlighted Seckinger High School in Gwinnett County, Georgia, a planned artificial intelligence-themed high school that will offer a college prep curriculum “taught through the lens of artificial intelligence.” Students will also be able to pursue an education in developing AI, she said.

A gap year for struggling students

Lake proposed that high schools and community colleges consider a new kind of post-high school “gap year” designed to help struggling high school graduates get back on track academically and prepare for college and careers.

“Gap years are oftentimes known for serving as a time for exploration for more advantaged kids,” she said. “Let’s change that.”

The idea is still in development, she said, but could be developed quickly.

“We don’t need to reinvent the wheel, but we need to get going,” she said.

While high school graduation rates are rising, the researchers said, so is grade inflation — 90% of parents believe their child is actually above grade level in reading and math, according to a March 2023 parent survey, making it likely that many students are exiting the K-12 system unprepared for college and careers.

Outside experts who study education systems and secondary education said CRPE’s alarm over the data is justified.

“There’s going to be a long tail of the pandemic,” said Robert Balfanz, a scholar who studies high school as co-director of the Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University.

He noted that the best predictor of whether a student will earn a college degree is if they earned “decent grades in challenging courses.” But if they don’t get access to these or don’t learn foundational material, “that’s a problem.”

Unequal access to such coursework, Balfanz said, can push students out of advanced classes.

He is concerned that during the pandemic, many students who “officially took calculus” or other advanced courses virtually may not have gotten all of the material required. “And those kids are probably already in college.”

In the paper, researchers lamented that our K-12 system “leaves to chance” nearly every aspect of the transition from high school to college and careers, from students discovering their interests and talents to selecting a career pathway aligned to them.

And few students ever get guidance on how to change careers and find new training or postsecondary opportunities when their interests and priorities shift.

“I think a combination of those factors is going to push some kids to delay post-secondary,” he said. “And the more you delay it, the odds of success are less.”

Trying to go back to school at that point, he said, is “always challenging.”

A new kind of report card

Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) at the American Institutes for Research, said COVID recovery “has not fully happened” in many schools.

“I’m not feeling super optimistic about pandemic recovery writ large right now,” he said.

But he said results from large-scale standardized exams “don’t resonate the way that information about their own students would resonate. What we need is for school systems to just be really clear with individual families about when their students are struggling. And I don’t think that school systems typically do that.”

Educators, he said, are typically optimistic about students’ chances of bouncing back — and fearful of being blamed for kids’ academic problems.

“Schools don’t have a ton of incentive to communicate in ways that might negatively bounce back to them,” he said.

Lake, the CRPE director, said one good way to fix this problem is simply to rethink report cards.

“Parents look to report cards first,” she said. “And report cards need to be able to say how the kids are actually doing — not just that they’re getting a particular grade. Are they mastering the skills that they need to graduate? Are they on track? And so that’s where I’d focus my efforts.”

Linda Jacobson contributed to this report.

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.