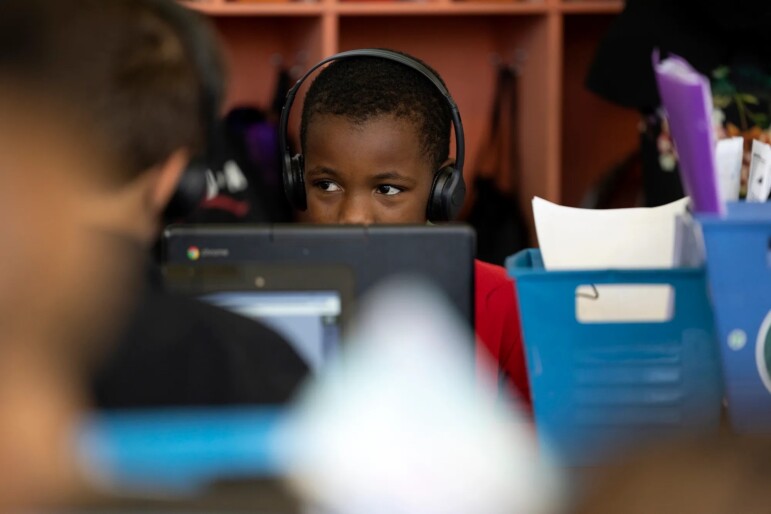

The use of education technology in schools, such as artificial intelligence, digital surveillance and content filters, poses a threat to the civil rights of students with disabilities, LGBTQ students and students of color, a new report warns.

Some technology used in schools to block explicit adult content and flag students at risk of self-harm or harming others have also created serious problems for already vulnerable students, cautions the report by the Center for Democracy and Technology, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that advocates for civil rights in the digital world.

The report is based on a wide-ranging online national survey about the technology used by schools, students and teachers. It was released on Wednesday, Sept. 20. This summer, the Center for Democracy and Technology polled 1,029 ninth- through 12th-grade students, 1,018 parents of sixth through 12th grade students and 1,005 teachers of sixth through 12th grade students in a sample the organization said was weighted to be “nationally representative.”

According to the Center for Democracy and Technology, the surveys also indicate widespread confusion about the role of artificial intelligence in the classroom, with a majority of parents, students and teachers saying they want more information and training about how to properly use it.

Report outlines education technology’s risks to students

The report outlines how school technology can, often inadvertently, harm students. The Center for Democracy and Technology says these harms are felt most acutely by vulnerable students.

Students reported incidents of LGBTQ classmates being outed by digital surveillance, a potentially traumatizing event of sharing their sexual identity or orientation without their consent.

Students with disabilities said they were most likely to use artificial intelligence — and they were more likely to report facing disciplinary action for using it.

One-third of teachers said content related to race or the LGBTQ community is more likely to be restricted by filters. The center said this “amounts to a digital book ban.”

Some schools have faced pushback for the way they deployed technology. After the American Civil Liberties Union sued a school district in Texas, the district loosened a filter that had blocked the website of the Trevor Project, a website aimed at LGBTQ youth.

“There are certain groups of students who should already be protected by existing civil rights laws, and yet they are still experiencing disproportionate and negative consequences because of the use of this education data and technology,” said Elizabeth Laird, director of equity in civic technology for the Center for Democracy and Technology.

Although schools often have dedicated staff and other practices set up to ensure that students’ civil rights are being protected, Laird said its survey indicates that schools have not fully wrestled with how education technology is affecting the promise of an equitable education, resulting in civil rights and technology being treated as separate issues.

“I think they’ve been kept separate, and the time is now to bring those together,” Laird said.

Civil rights groups call for more federal guidance

While schools have been conducting more outreach than in previous years, the survey shows an increase in student and parent concerns about data and privacy over the past year. Survey data collected in previous years shows both parents and students need more outreach and engagement on how schools are selecting and using technology.

Last October, the White House released a Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, but civil rights groups — including the ACLU, the American Association of School Librarians, American Library Association, Disability Rights in Education Defense Fund and the Electronic Frontier Foundation — signed a letter accompanying the Center for Democracy and Technology’s report, petitioning the federal Department of Education for more guidance.

“In the year since the release of the Blueprint, the need for education-related protections remains and, if anything, is even more urgent with the explosive emergence of generative AI,” according to the letter.

Fifty-seven percent of teachers in the survey stated they haven’t had any substantive training in AI, while 24% say they have received training in how to detect inappropriate use of AI.

The survey also found that 58% of students have used ChatGPT or other generative AI programs, and 19% said they have submitted a paper written using AI. Students report using AI both for school assignments and for dealing with mental health issues or personal problems with family and friends.

Students with disabilities are more likely to use generative AI: 72% said they’ve used the technology.

Parents of students with disabilities are more likely to say that their students have been disciplined for their use of artificial intelligence. The report calls higher rates of discipline among vulnerable communities “particularly worrisome.”

These students and their parents — 71% of students with disabilities and 79% of their parents — express more concern than others about the privacy and security of the data collected and stored by the school.

Licensed special education teachers are more likely to have conversations with students and their parents about student privacy and equity issues in technology, a “promising practice that could be extended to the rest of the school population,” the Center for Democracy and Technology recommends.

School surveillance’s long arm

The civil rights issues can go beyond the walls of the school. Some students, particularly students of color and those from lower-income communities are more likely to rely on school-issued devices when they are at home. Monitoring and tracking can therefore follow them home.

“Their learning environment for those students is quite different than those who can essentially opt out of some of this tracking,” Laird said.

Students who use technology devices to charge their personal phones may also find that this technology will scan and monitor these personal devices as well. Among students who have used their school device for charging, 51% said school software began syncing with and downloading content from their personal device.

Monitoring technology became prevalent in the pandemic-era remote learning, but it has persisted, with 88% of teachers reporting their schools use the technology. The White House named preventing the unchecked monitoring of students a priority in its blueprint. The Center for Democracy and Technology says that the use of surveillance technology can cause a host of problems for students.

Students with disabilities and LGBTQ students are more likely to report being disciplined as a result of technology that monitors them. Laird said that sometimes students are disciplined for something the technology flagged, but other times, they are disciplined because of their reaction to being flagged.

Schools sometimes share data directly with law enforcement — even after school hours. Fifty-three percent of special education teachers and 46% of teachers in Title I schools said data was shared with law enforcement after hours. During an interview with the Center for Democracy and Technology, the parent of a ninth grader said that law enforcement was contacted even before she was notified when something on her child’s device was flagged by the school’s monitoring technology. Her son was questioned for an hour without her consent.

“All of those things can result in students being removed from the classroom and losing instructional time,” said Laird. “And so if those students are being disproportionately flagged and being intervened in a disproportionate way, this could also be a potential violation of [a student’s right to a free and appropriate public education], which is specific to preventing discrimination on the basis of disability.”