Oshun O’Rourke waded into the dark green water, splashing toward a net that her colleagues gently closed around a cluster of finger-length fish.

The Klamath River is wide and still here, making its final turn north to the coast as it winds through the Yurok reservation in Humboldt County. About 150 baby chinook salmon, on their long journey to the Pacific, were resting in cool waters that poured down from the forest.

O’Rourke’s colleagues hoisted the net into a mesh-sided bin in the shallows to sort through their catch, in search of young chinook to test for a parasite that can rot fish from the inside.

Two years ago, during a deepening drought, most salmon captured for testing during peak migration were infected with the lethal parasite. One tribal leader called it “an absolute worst-case scenario” for the Yurok, who rely on salmon for their food, culture and economy.

O’Rourke and fisheries biologist Leanne Knutson laid out 20 small dead fish on paper towels, then wrapped them in plastic to send to a lab that will check for the parasite. The rest were released back into the river, where they will swim for days to reach the ocean.

A few years from now, when these fish return as adults ready to spawn, it will be to a Klamath remade.

“These ones will return either as three or four-year-olds,” O’Rourke said, standing barefoot on the riverbank flecked with fool’s gold and crossed by an otter’s footprints. “And the dams will be gone.”

For more than a hundred years, dams have stilled the Klamath’s flows, jeopardizing the salmon and other fish, and creating ideal conditions for the parasite to spread.

But now these vestiges of an early 20th-century approach to water and power are being dismantled: The world’s largest dam removal project is now underway on the Klamath River.

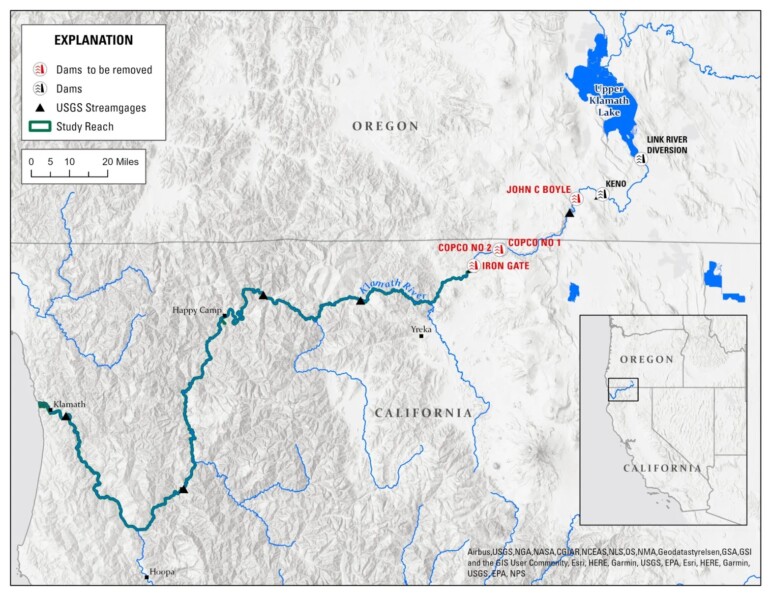

By the end of 2024, four aging hydroelectric dams spanning the California-Oregon state line will be gone. One hundred thousand cubic yards of concrete, 1.3 million cubic yards of earth and 2,000 tons of steel will be hauled out of the river’s path.

Tribal members, researchers, rural residents near the dams, conservationists and the fishing industry are all anxiously waiting to see how this river, dammed for decades, will change — and with it, its fish, wildlife and human neighbors.

It’s an existential question for rivers, especially in a region where water left in nature is often deemed wasted: “Once a river is dammed, is it damned forever?” experts ask.

So many uncertainties remain as the Klamath reemerges: Will sediment from the demolition harm the river and its inhabitants? Will healthy numbers of salmon finally return? Will it flood its banks more readily? What will the riverfront look like?

For O’Rourke, 31, a Yurok tribal member, the Klamath is more than a study subject — it’s home for her and her team, and the lifeblood of their tribe, which has inhabited this region since time immemorial. From the research boat, she gestures to the stretch of river where she grew up in her ancestral village, fishing with her father.

O’Rourke is hopeful that tearing down the dams will mean her son will have salmon to fish, too. But, as a scientist, she plans to investigate, seeking evidence that the river will rebound for the next generation.

“It’s hard to say for sure,” she said, “what things will be like in the future.”

The Klamath is often described as an upside-down river. It’s born in the high deserts of eastern Oregon as a trickle, and by the time it reaches the Pacific more than 250 miles later, it swells with water drained from more than 12,000 square miles of land, spanning five national forests and seven counties across two states.

There’s a stretch of river, crossing the California-Oregon state line, where feral horses pick their way up pine-studded slopes and osprey nest on power poles.

This is where, in 1918, a power company began operating the first of its hydroelectric dams on the river to light the towns and power the farms, mines and mills of California’s far north and Oregon beyond.

This is where dam construction dispossessed the Shasta people, blockaded salmon runs and stewed the river’s water into a warm, algal brew — drawing decades of activism from tribes and conservationists.

And this is where demolition has begun.

For more than 20 years, four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath have been at the center of a fight to restore the river.

The dams weren’t built to store water for drinking, irrigation, or to stop floods. They generated electricity for PacifiCorp, a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy, producing less than 2% of its customers’ power supply.

On one side are Native tribes in California and Oregon, conservationists and the fishing industry — all fighting to restore native salmon, steelhead and Pacific lamprey that have dwindled under the combined threats of changing ocean conditions, farming and ranching, timber harvesting, mining, overfishing and dams.

On the other side are nearby residents and their politicians, who see demolition as another way for state and federal agencies to impose their environmental wills on their rural way of life.

And in the middle is PacifiCorp. The company had planned to continue operating the dams to generate electricity after its license expired in 2006. But by 2010, facing growing protests and hundreds of millions of dollars in federally mandated updates to make them less dangerous to fish, PacifiCorp agreed to demolish them.

Deals between the company, California, Oregon, the Secretary of the Interior and others were struck, blocked in Congress, and remade until, last November, when federal energy regulators gave their final blessing to demolish the dams.

“It’s about damn time we got this done,” California Gov. Gavin Newsom said in December at the fish hatchery below Iron Gate dam, the most downstream of the dams slated for demolition.

California taxpayers will cover $250 million of the roughly $450-$500 million bill with funds from the Proposition 1 water bond approved by voters in 2014. Another $200 million comes from surcharges that PacifiCorp customers, mostly in Oregon, have already paid.

For California officials, the cost of demolishing a private company’s infrastructure is worth the benefit of a more free-flowing river.

“Sometimes, the need to do something so bold — to fix a place and right past wrongs — means you have to sit down and just be pragmatic on how you’re going to get a deal done,” Chuck Bonham, director of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, told CalMatters.

Native tribes and scientists see demolition as a victory for the river’s first peoples and the fish they depend on for their food, cultures and livelihoods. Chinook populations have crashed, so much so that the 2023 fishing season was cancelled statewide. The river’s spring-run chinook are listed as threatened under California endangered species law, while coho are listed under both the state and federal laws.

Removing the dams is expected to reopen more than 400 miles of habitat for steelhead and other threatened and iconic fish, and restore flows that can better flush away toxic algae and disease.

But residents and officials in Siskiyou County worry about the sediment that the project will unleash into the river and the consequences of losing a reservoir to refeed groundwater wells, fight fires and recreate.

Landowners mourn lakeside property that will no longer be waterfront as reservoirs vanish and the exposed land becomes the property of the state of California or a designated third party.

What is clear is that the Klamath won’t return to the river it once was. Designated as a wild and scenic river, the Klamath has long been the nexus of some of the West’s fiercest water wars, and removing PacifiCorp’s hydroelectric dams ends only some of the battles.

Other dams will remain upriver in Oregon, where the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation controls flows from Upper Klamath Lake — portioning out too little water to satisfy tribes, wildlife refuges, lake, river, farms and fish. The battle over water allocation will continue, as will the fights over tributaries downstream of the dams.

“The work is not done, by any means,” O’Rourke said, the Klamath River rushing beside her. “There’s still so much to do after the dams come out.”

The smallest of the four dams, the 33-foot Copco Number 2, located in Siskiyou County, is already almost gone. Water rushed past it by mid-July, and only a concrete and steel structure on the river’s bank remained visible from above.

“Quite a remarkable sight to see and feeling to feel,” said Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the nonprofit formed to oversee the removal effort. “Knowing that we’ve broken ground and allowed for the river to start that healing.”

This time last year, Bransom said, the riverbed was dry, the water diverted to generate power. Trees now crowd the canyon floor where they sprouted from a riverbed long absent its river.

By October of 2024, the river will flow freely past the other three dams as well — the J.C. Boyle dam in Oregon and the Copco Number 1 and Iron Gate dams in California’s Siskiyou County.

At this point, Bransom said, “there is no going back.”

Driving around the mirror-still reservoirs reveals clusters of activity.

Neon-vested workers on the hillsides collect seeds to replant the bare landscape exposed by drained reservoirs. Overlooking Copco Number 1 dam, the pop-pop-pop of target practice in the distance is audible over the din of drilling for a new groundwater monitoring well.

From a hillside above Iron Gate dam, Bransom explains the vast undertaking that is unmaking four dams and a century of environmental interference.

Starting in January 2024, contractor Kiewit Infrastructure West will use explosives to blast out concrete walls beneath the spillway at J.C. Boyle dam in Oregon and remove the last plug of concrete from a tunnel drilled into the Copco Number 1 dam downstream. Water will flow into Iron Gate reservoir.

A yellow front-end loader trundles to a tunnel at the base of the Iron Gate dam, next to the spillway. This tunnel is where every drop of muddy water will pour into the river starting in January, draining Iron Gate reservoir by up to about 5 feet a day.

About 20 million cubic yards of sediment have collected behind the dams over decades — enough to fill about 2 million dump trucks, though only about a quarter to a third of it is expected to end up in the river, Bransom said.

The sediment can choke salmon and other life, and cause oxygen levels in the river to drop. But the work will be timed to avoid migrations, and the ill effects are expected to diminish with time and distance. Federal officials report that ultimately the new conditions will be beneficial to the river and its fish.

From June through October, excavators will dig into the earthen parts of J.C. Boyle dam in Oregon and use the material to fill in an eroded riverbank and the canal diverting water to the powerhouse.

Contractors will use explosives to break up the concrete of the Copco Number 1 dam into chunks and cart it away. Iron Gate will be unzipped from top to bottom by excavators that will deposit the earth in the spillway and a scar left by the dam’s construction.

Restoration will also start when the reservoirs are drained, replanting the newly exposed land and restoring habitat.

Looking down at Iron Gate dam, where water still churns from the turbines generating power, Bransom said he thinks of the river as a creature exploring new territory.

“I’m most curious and excited to basically watch the river emerge, and to see where the river wants to find its way back through this area where it’s been so constrained for 100 years,” Bransom said. “There’ll be some curiosities and trepidation, but it will be only forward progress.”

In the meantime, newlyweds Francis Gill and Danny Fontaine are living in limbo in the Copco Lake community, built on the reservoir, soon to vanish, formed by the Copco Number 1 dam.

Gill, chief of the Copco Lake volunteer fire department, and Fontaine, a realtor, own a home, rental properties, the long-empty Copco Lake store and a workshop next door. Gill estimates that around 75 to 85 people live in the community full time — double that when those with vacation homes are there.

At Gill and Fontaine’s workshop, a sign on the wall lists Lake Rules. “Go barefoot,” reads one. “Jump off the dock.” But the water has already lowered enough during deconstruction that the dock now rests on the reservoir’s grassy bank, foreshadowing the future.

At first, when the deal was finalized, they were angry — a feeling that reverberates across Siskiyou County, which has long chafed against the reach of state and federal agencies meddling with local industries. County residents overwhelmingly voted to keep the dams.

Now, with dam removal starting in earnest, Gill and Fontaine are feeling more resigned.

“It’s kind of like a facelift,” Fontaine said. “What’s it going to look like? I hope it looks good!”

“Do I really trust this doctor?” Gill joked.

State and federal environmental assessments spell out the potential impacts on local residents, including the loss of lakewater for firefighting, some unstable lakeside slopes and a drop in groundwater levels.

Downstream of the dams, floodwaters could rise as much as 20 inches higher during extreme, 100-year-floods, with levels dropping back down to normal 19 miles downstream, according to federal projections.

Some of the money in the budget — the dam removal corporation won’t say how much — has been set aside for an independently managed mitigation fund that residents can apply to, provided they agree not to sue. CalFire has also signed off on a plan to address local firefighting capacity, which includes dry hydrants and a camera network to spot fires.

Gill and Fontaine fear they will lose access to the water their community was built around. They are holding out hope that at least the river will be close, feeling for the bottom of the lake when they go swimming and measuring it with a depth probe, looking for the river’s original channel. Fontaine thinks he discovered it while swimming off of the store’s boat ramp.

“It was kind of exciting, that maybe it could be right there. But we don’t know,” he said.

They are clear-eyed about the algae that turns the lake green every summer. But the two aren’t convinced that removing the dams will fix it. Gill said he heard that before the dams were constructed, the river would slow to a trickle between puddles of algae in the summer.

The river’s flows will continue to be controlled by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which declined to answer CalMatters’ questions.

The original locals, the Shasta Indian Nation, also have mixed feelings about the dam removal. Though they support the river’s restoration, they’re bracing for what deconstruction and drainage will reveal. Dispossessed by the dam’s construction, the Shasta Indian Nation now faces disturbance once again of burials and other cultural sites.

“There are consequences with the construction of the dams,” said Sami Jo Difuntorum, culture preservation officer of the Shasta Indian Nation. “And now with the dams coming out, we have consequences that are unique to our people — the disruption and disturbance to our sacred sites.”

Richard Marshall, president of the Siskiyou County Water Users Association, which opposes dam removal, doubts the disruption will be worth it. The idea that demolition is going to “automatically create salmon,” he said, “is simply not true.”

Marshall suspects that warm water upriver, underwater barriers to fish migration and predators have always made the upper basin inhospitable to salmon.

Federal scientists disagree. They point to historical descriptions of chinook, steelhead, coho salmon and lamprey above the dams. A photograph from the Klamath County Historical Society from 1891 shows men in suits, ties and hats displaying their salmon catch on the Link River, which flows from Upper Klamath Lake.

It’s a matter of timing, said Jim Simondet, Klamath branch supervisor for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s fisheries division. Temperatures should be cold enough and flows sufficient for spring-run chinook salmon, a state-protected species, to migrate above the dams in the spring, but should also support fall-run chinook migrating after the heat of the summer subsides.

Simondet said scientists will be keeping a close watch for any bottlenecks that might prevent fish from reaching the upper basin.

“There’s a lot of fish that are bumping their heads up against Iron Gate Dam currently,” he said.

The river’s coho salmon, listed as threatened at the state and federal level, are also expected to use about 70 miles of habitat above the former dam sites after demolition, Simondet said.

Mike Polmateer is helping the Karuk tribe track them — if and when they do return.

“We believe wholeheartedly that once the dams come down, the fish will return,” said Polmateer, a field supervisor with the Karuk Tribal Fisheries Program. The Karuk and the Yurok downriver are the largest tribes in California.

Polmateer is also a traditional fisherman and a fatawana, which he describes as a medicine man. He’s been protesting the dams for years, after a massive fish die-off on the lower Klamath in 2002 catalyzed the movement to restore the river.

“That’s still the water that runs through my veins. We only want it to be taken care of,” Polmateer said.

Highway 96 unfurls along the river from the dry volcanic slopes downstream of the dams to wooded canyons downriver. And just off the highway, tucked away down a bumpy dirt road where horned cattle rest in the shade, is a clear blue pond built as a refuge for young coho salmon.

Polmateer meets his team there — three younger men in wetsuits who wade into the pond to capture the small silver fish for tagging.

The operation takes seconds: The fish, less than three inches long, are sedated in a bucket of water laced with clove oil and something more, then weighed, measured and scanned for existing tags. Then, a deft poke into the fish’s abdomen with a needle, and a tag, no bigger than a grain of rice, is slipped inside.

Tagged, these coho can be tracked on their way to the ocean and as they return, after the dams are gone.

Polmateer, now 63, will be retired by then, but he hopes that his crew, the next generation, will continue the work.

“It’s more than just a river to us. It’s more than just something that harbors fish,” Polmateer said. “It’s who we are as a people. We’re fix-the-world-people, Karuk people are.”

Green gobbets of algae raced down the Klamath about 11 miles downriver of Iron Gate dam. Big rigs roared in the opposite direction on Interstate 5 above, rumbling towards Oregon.

And in the middle of the river, water up to his knees, stood Yurok fisheries technician Gilbert Meyers, a net plunged into the gravel and muck. A team of researchers was there to take the river’s pulse.

One way to do that, said Meyers’ boss, Jamie Holt, is by capturing bugs.

“Fish eat bugs, so it directly equates to fish food,” said Holt, a senior fisheries technician with the Yurok Tribe’s Klamath program.

Monitoring which insects like mayflies, caddisflies and salmon flies are living where, and in what numbers, offers a real-time view into the river’s health before and after the dams come down. The work, a collaboration with UC Davis and California Trout, spans the basin, fingerprinting conditions on the Klamath over time.

The crew’s next sampling location, at a campground downriver, is more scenic than the site under I-5. But here, too, algae clogs the sampling nets.

A flotilla of children on rafts have scared away the fish the team tries to survey, and they break for food — salmon that Yurok fisheries technician Keenan O’Rourke caught, smoked and jarred last summer.

This year, salmon projections are so dismal that federal officials and the Yurok tribe canceled commercial and subsistence fisheries, a devastating decision for people with an average income of less than $21,000 a year.

Holt warns that the dam removal won’t be a panacea as the federal government will still control flows upriver. But she’s optimistic about all the ways it will improve the river’s health. “It’s just going to harbor far more life … It’s going to hatch all kinds of bugs, which grow bigger fish,” she said.

Holt’s been hearing about demolition of the dams for so long that it doesn’t seem real that they’ll soon be gone.

“I kind of joked around for a lot of years that I’ll believe it when I’m floating over where they used to stand,” she said. “And it still kind of holds.”