In a major about-face, Gov. Gavin Newsom gave ground this week on his signature mental health plan, aiming to appease critics who have argued his overhaul would starve youth services and other county-run programs of millions of dollars of tax revenue.

The proposal is the second time in as many years that Newsom has advocated for significant changes to the state’s behavioral health system, following the passage of last year’s controversial CARE Court law. This year’s proposal aims to update the Mental Health Services Act, a 20-year-old ballot initiative that has raised billions of dollars per year for mental health programs through a tax on high incomes. The tax funds nearly one-third of the state’s mental health infrastructure and raised $4.8 billion last year.

At its crux, Newsom’s proposal would require counties to spend two-thirds of revenue from the tax on housing and 24/7 services for the state’s severely mentally ill homeless population. That equates to roughly $3.1 billion based on last year’s Mental Health Services Act revenue.

Some of the concessions introduced this week would loosen the definition of the “housing interventions” counties would be required to fund, reinstate some local spending flexibility, remove a requirement to add services for people suffering from addiction, and carve out money for children and youth programs.

Newsom’s reform needs more than legislative buy-in. It also requires voter support to change the original ballot initiative. His pitch to voters: Redirect some of the money in an effort to help address California’s out-of-control homelessness crisis. The state has spent more than $20 billion on homelessness in the past five years with little impact.

However, key mental health advocates remain skeptical. Many of the organizations that voiced concerns with the initial proposal say the recent amendments are “weak” and continue to stretch vital resources too thin.

“We’re still slicing up the too-small pie,” said Clare Cortright, policy director for Cal Voices, a coalition of mental health peer support organizations. “What happens to the people with services now? What happens to the people with housing now?”

The plan, which mental health groups have criticized for being rushed, will get its first full legislative hearing next week. Lawmakers then would have four weeks before the end of the session to decide whether to place the measure on the March 2024 ballot.

Newsom argues that his administration has spent “years preparing for this” overhaul in tandem with other major changes to the state’s health care delivery system.

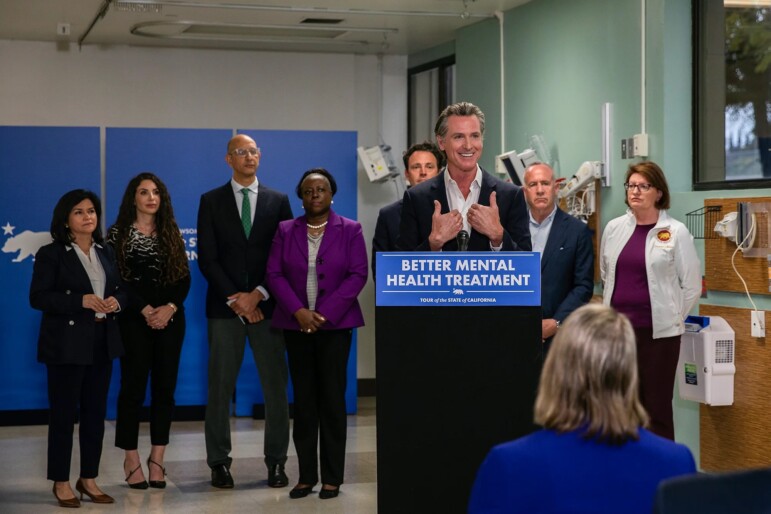

“We’ve organized this very deliberatively,” Newsom told reporters last week. “This is very methodical, very focused. It’s not ready, fire, aim. It’s ready, aim, fire. It’s long overdue, and the consequences of neglect, delay denial — it’s too great.”

While Tuesday night’s amendments preserve the most significant change Newsom put forward — that a majority of the money be used on housing interventions and intensive services for unhoused people — it offers counties more local control.

The amended proposal:

- Allows counties to transfer some money between spending categories like housing and prevention

- Offers small counties with more volatile year-to-year budgets exemptions from meeting some mandates

- Increases the amount of money allocated to the “flexible” spending bucket by 5%

- Expands the definition of housing interventions to include a wide range of social services like housing navigation rather than only “hard” costs like rent

- Requires 51% of money spent on prevention programs go toward children and youth

- Reinstates some of the power previously stripped from the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Committee.

“We’ve seen some changes and certainly changes that seem helpful in moving to ameliorate some of the concerns that we’ve had. However, there’s also a bunch of new stuff in here that we’re trying to figure out,” said Jacqueline Wong-Hernandez, chief policy officer for the California State Association of Counties.

County leaders and behavioral health directors are most concerned with proposed minimum spending mandates that are funded through volatile income tax revenue. The Mental Health Services Act levies a 1% tax on earnings over $1 million, an income bracket that depends on capital gains. They have also questioned how many existing services would be cut to meet the new housing mandate.

The amendments come on the heels of several Legislative Analyst’s Office briefs that estimated $718 million would be stripped from existing county mental health programs, including children and youth early intervention services, to fund the proposed housing mandate. The briefs said the Newsom administration gave “incomplete justification” for the changes without an impact analysis.

Despite Newsom investing significant political capital into pushing this reform, it became increasingly difficult to ignore the opposition of children’s mental health advocates, who said the governor was unnecessarily pitting the needs of the state’s homeless population against children’s mental services. Prevention and early intervention services would take the biggest cuts, they said, ultimately worsening a parallel mental health crisis.

Last week a coalition of nearly 300 groups representing local mental health agencies, school districts, and family resource centers among others, sent a letter to Newsom and Senate Health Committee Chair Susan Talamantes-Eggman, urging them to continue funding programs targeting ages 0 to 25. Eggman, a Democrat from Stockton, is carrying the bill that would place Newsom’s proposal on the ballot and was instrumental in passing Newsom’s CARE Court legislation last year. Eggman has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

“For years, children’s advocates have worked to ensure (this) funding prioritizes children and youth given the historic lack of focus on this population,” the letter states. “We are deeply concerned by the current proposal … to severely limit and reroute hard fought investments away from child-serving programs.”

The amendments address the primary concerns raised by the coalition and preserve a majority of the roughly $448 million spent on children and youth mental health programs annually, said Adrienne Shilton, a lobbyist for the California Alliance of Child and Family Services.

“We’re moving in a positive direction here,” Shilton said. “The administration has come a long way in partnership with us.”

Newsom administration officials contend that the proposal is part of a larger effort to remake the state’s health care system. They point to last year’s $4.3 billion budget allocation for children and youth mental health services and Medi-Cal as alternate funding sources for current programs. But advocates say a majority of that investment comes from one-time allocations and integral programs like family support groups, parenting classes and suicide prevention programs don’t qualify for Medi-Cal reimbursement.

Courtney Armstrong, director of government affairs with the First 5 Association of California, said roughly 95% of programs statewide that serve infants and children up to age 5 are not reimbursable through Medi-Cal.

Despite the concessions, disability rights groups, peer support advocates, and many of the advocates that opposed last year’s CARE Court legislation are still against this version of Newsom’s overhaul. They want more assurances that the money won’t be used to place homeless people in locked treatment facilities against their will.

“The average Californian absolutely wants more services and more housing for those who need it most, but they don’t want to be duped into funding the legal system and criminalization of communities of color and more involuntary institutionalization,” said Carolina Valle, senior policy director with the California Pan Ethnic Health Network.

Historically institutionalization and jail-based services have disproportionately impacted communities of color, Valle said. Critics also point out that California’s homelessness crisis is primarily driven by lack of affordable housing and incomes that have not kept pace with the cost of living, not mental illness.

“This budget fight around the (Mental Health Services Act) is not a moment in time. It’s a continuation of failed mental health policy and failed housing policy in California,” Valle said.