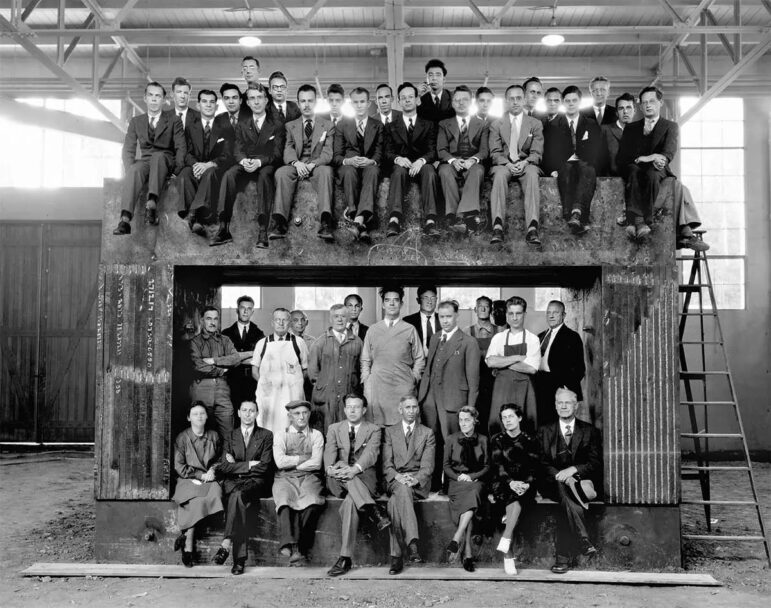

It was the summer of 1942 and a secret group of senior theoretical physicists at the University of California, Berkeley — dubbed the “luminaries” — took the historic first steps toward the design and manufacture of the world’s first nuclear weapon, the atomic bomb.

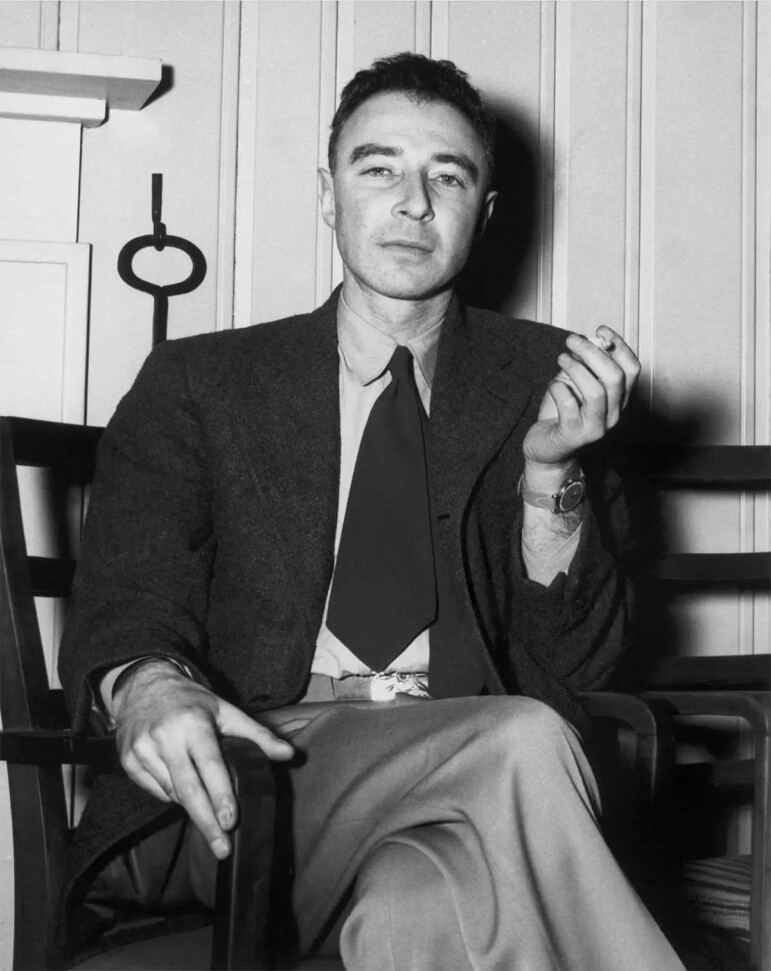

Amid World War II, which began in 1939, the luminaries joined U.S. and Allied forces against Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, Japan and Italy. Enter American physicist Julius Robert Oppenheimer, also known as “the father of the atomic bomb,” the director of the secret U.S. Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the leader of the group he jokingly called the “luminaries.”

The group — which included Hans Bethe, Felix Bloch, Emil Konopinski, Edward Teller, John Van Vleck, Robert Serber and some physics graduate level Berkeley students — assembled at the Berkeley campus, where Oppenheimer also taught physics and eventually filled the two corner offices, 433 and 435, on the top floor of LeConte Hall, now Physics South.

Nearly 80 years later, the world-renowned director Christopher Nolan shot a number of scenes for the new biopic “Oppenheimer” on UC Berkeley’s campus. Based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s book “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” the Universal Pictures film is set to release on July 21, 2023. Nolan’s cast includes Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer, Emily Blunt, Florence Pugh, Robert Downey Jr., Matt Damon, Josh Peck, Rami Malek, and more.

The film is centered around the atomic bomb debate during the war, the physics behind the Manhattan Project’s atomic bomb, and the pivotal role Oppenheimer and his colleagues played in winning a world war.

It’s also a Christopher Nolan movie — and some Nolan fans are claiming it is their “most anticipated 2023 release,” following his 2020 action sci-fi “Tenet.” Notably, it will be the first movie to combine shooting in IMAX 65mm with IMAX black-and-white analog photography, which requires a huge screening canvas.

Shooting locations included Oppenheimer’s offices, the Physics South building on South Drive and Oppenheimer Way surrounding Physics South and the pathway leading up to the west side of the Campanile clock tower.

Anthony Vitan, facilities director for UC Berkeley’s math and physical sciences departments, worked as one of the primary liaisons for UC Berkeley and the “Oppenheimer” site production manager during filming in May.

“I was very interested and excited because I knew it was a Christopher Nolan movie, and I’ve been a big fan of his films for quite a while. What a great opportunity, like once in a lifetime, to be able to support a major production here on campus and the historical part of Berkeley,” Vitan said.

Vitan assisted the site production manager and worked on logistical issues such as guiding foot traffic both inside and outside where Nolan filmed. A “starstruck” Vitan then met and offered his office to Cillian Murphy as a “quiet, private” changing room throughout the day of filming. He said he purposely left out an “Oppenheimer” book on his desk and that Murphy ended up autographing it for him.

But Vitan wasn’t the only Berkeley personnel involved in “Oppenheimer.”

Incoming senior Troy Bronson landed a role in the movie and will play Joseph W. Kennedy, a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley who co-discovered plutonium. Kennedy demonstrated to Oppenheimer that plutonium is indeed fissile — meaning capable of a nuclear chain reaction.

Bronson said it was “magical” to take on a 1930s character on his campus in a $100 million budget movie. He traded his typical attire of shorts for slacks, heavy boots, and two outfits that took 17 tries for the costume design department to master and then tailor on-site.

“You had it all to dress the school precisely like it was back then, from the cars, bikes, props such as some of my books tied with worn down leather strings,” Bronson said.

“The custom design department making sure to fix even the slightest thing such as raising or lowering down pants one to four inches and making sure no more than one [actor] would be wearing a similar color when in a group or meeting.”

Berkeley was Oppenheimer’s “favorite place,” he said. The scientist was also a favorite among students, who nicknamed him “Oppi,” according to the Berkeley Historical Plaque Project.

During filming, props concealed the modernization of the campus in the years since 1930s and 1940s. Production crews designed boxes to cover blue emergency LED light poles and added old bells to the landscape. Bushes and plants covered bicycle racks and stackable wooden boxes hid trash cans. Lines striping the roads were covered with tape and painted to match the color of the asphalt. Electricians also hung older era light fixtures outside the physics building.

The campus-turned-studio transformation caught the attention of university staff.

“I couldn’t help but pull out my phone from a little corner office over there to see some of the filming, which was one moment where I did feel starstruck,” James Analytis, current chair of the physics department at UC Berkeley, said of the “Oppenheimer” filming.

“We’ll see what the film looks like, but it’s such an exciting event to have a spotlight on what truly has been a very important department in the history of physics and the world,” Analytis said.

Analytis said he understood that Oppenheimer was “empathetic, earnest and concerned with how science impacted the world.”

He said Oppenheimer was concerned about the communication of science to the public throughout his career and this took a certain “selflessness.”

Oppenheimer’s classes were more like “long talks” with no set times, according to Bronson. He would gather around lab tables at the Physics building with his students.

“Probably the loneliest part on campus, but if you keep walking and cross one of the two little bridges [near the physics building] it’s just like stepping into the past of Berkeley,” Bronson said. “There has not been any development there, it is very green, hidden by trees. Oppenheimer would spend a lot of time there; you might see them in the film.”

In the fall of 1941, one year before the creation of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was urged into the secret work of the atomic bomb by Ernest Orlando Lawrence, a former Berkeley physics professor, nuclear physicist and the Nobel Prize in Physics winner in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron.

By spring 1942, Oppenheimer recruited Robert Serber, a Nuclear Regulatory Commission fellow, to work with him and two other graduate students, Eldred C. Nelson and Stanley P. Frankel, on problems of neutron diffusion and what it meant for the explosion of a uranium fission bomb.

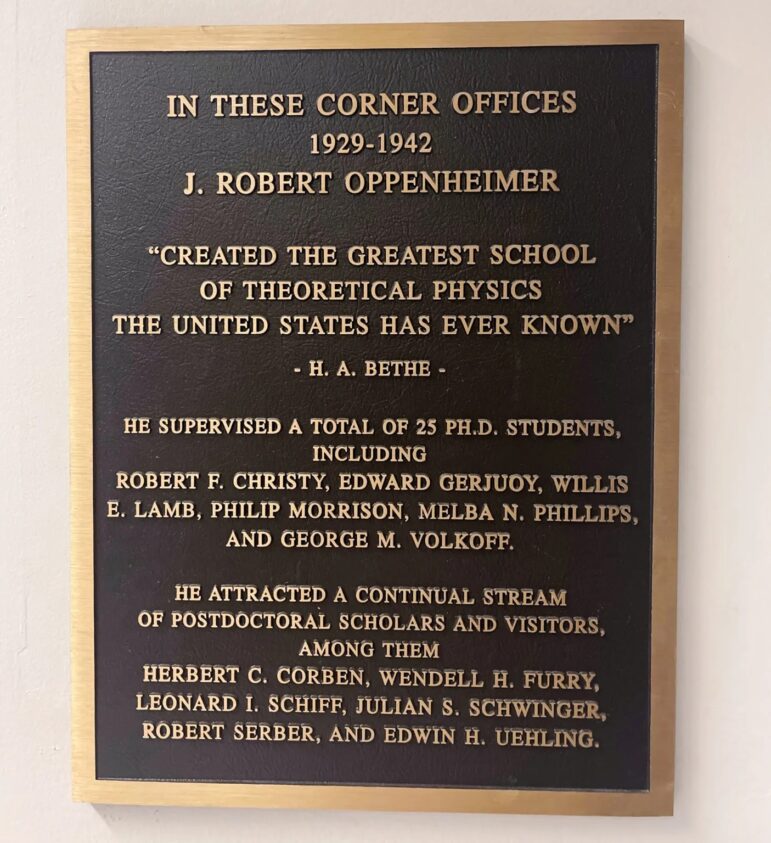

“The group met secretly in his office at the northwest corner of the top floor of ‘old’ LeConte Hall. This office, like others on the top floor, has glass doors opening out onto a balcony. This balcony is readily accessible from the roof. To prevent this method of entry, a very heavy iron netting was placed over the balcony. A special lock was placed on the door to the office [room 435] and only Oppenheimer had the key. No janitor could enter the office, nor could I, as chairman of the department,” Raymond T. Birge, former chair of the Berkeley physics department at the time, said in his “History of the Physics Department.”

Room 435 had an extra lock and iron grillwork. Inside, a massive iron safe held the papers and secrets to the Manhattan Project. The safe was so heavy it sank the elevator to the basement instead of rising to the top floor.

Bethe said Oppenheimer established UC Berkeley as the “greatest school of theoretical physics the United States has ever known,” according to a plaque outside Oppenheimer’s offices.

Oppenheimer was later celebrated for his achievements and received the Enrico Fermi Award by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963 for his contributions to theoretical physics.

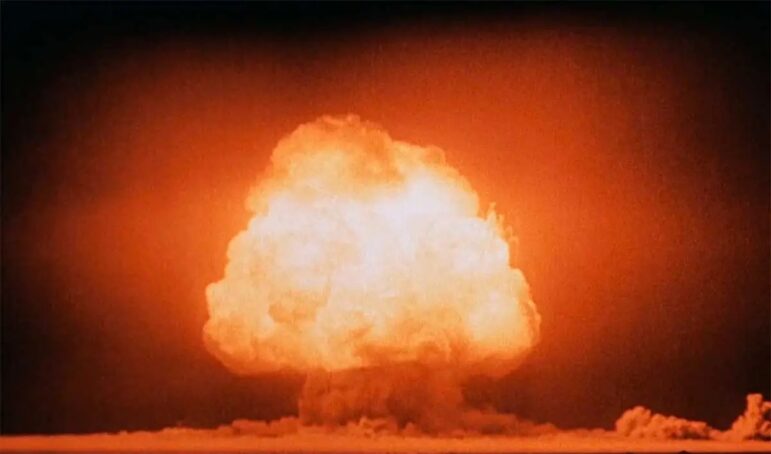

On July 16, 1945, the world’s first nuclear explosion occurred under the Manhattan Project when their code-named “Gadget,” an implosion plutonium device, exploded in the New Mexico desert, 200 miles south of Los Alamos.

Named the “Trinity Test,” it was described as though “the whole country was lit by golden, purple, violet, blue and gray searing lights” by U.S. Army Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell. The bomb released between 15 and up to 20 kilotons of force, slightly more than the “Little Boy” bomb that was dropped by U.S. forces on Hiroshima in Japan 21 days later.

The Manhattan Project, a U.S. Government research initiative, cost $2 billion, which would be nearly $36 billion today. The project brought scientists and physicists, including Oppenheimer, across the U.S. under the direction of U.S. Lt. General Leslie Groves Jr., a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon.

Secret bomb-making factories spanned across American cities, including the laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, as well as nuclear reactors in Hanford, Washington, and a uranium processing plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

“It’s a funny legacy, because, on the one hand, I guess he was doing what he felt was his duty to his country, to help give America and the Allies the weapons that they needed to defeat fascism, which would have been a very real threat back then. But then also grappling with the destructive power of what they created,” Analytis said.

In 1945, the feelings of becoming “death” and a “destroyer” followed him after the bombings of Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and Nagasaki on Aug. 9 that killed thousands of people immediately upon impact and then deadly radiation that killed thousands more. On Aug. 17, Oppenheimer expressed in writing to the U.S. Government his desire for nuclear weapons to be banned. Two months afterward, he told President Harry S. Truman that “blood was on his hands.”

“I think he had mixed feelings about what we should do with this technology, and immediately following World War II after the atomic bomb, the Atomic Energy Commission was trying to develop the hydrogen bomb, which was going to be 10, 100 times more powerful or something like that,” Analytis said. “And he was against the development of the hydrogen bomb, and the result of that was that he was implicated as being a Communist sympathizer. That almost destroyed his career.”

Regardless, Oppenheimer’s legacy still lives on at Berkeley. The university holds an annual public Oppenheimer Lecture, bringing in theorists and physicists around the world. Last year’s guest speaker was Leonard Susskind, a professor of theoretical physics at Stanford University and founding director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Analytis said the movie is “a highlight of how important the University of California has been to the history of science and building their modern society and Oppenheimer is one of those super influential figures that has had a big impact.”