Just when California’s teacher shortage seemed to be easing, it got worse. A seven-year increase in the number of new teacher credentials issued by the state ended last year with a 16% decline, exacerbating the state’s ongoing teacher shortage.

There were 16,491 new teaching credentials issued in California in 2021-22, the most recent fiscal year data available. The previous year, the state bestowed 19,659 such credentials, according to “Teacher Supply in California,“ an annual report to the state Legislature compiled by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing.

Three thousand fewer teachers could have a significant impact on California school districts already struggling to fill teaching positions. Without enough credentialed teachers, schools have had to hire teachers on emergency-style permits that don’t require them to complete teacher training.

Elementary schools, which primarily employ teachers with multiple-subject teaching credentials, may feel the shortage the most. There were 25% fewer new multiple-subject credentials issued in 2021-22 than in the previous year.

New special education credentials declined by 12%, and new single-subject credentials, mostly issued to secondary school teachers, went down 7%.

“The past few years have been really tumultuous for students and teachers, and many factors have impacted that,” said Jana Luft, interim associate director of educator engagement at The Education Trust-West, a nonprofit education advocacy organization. “It may be a while to see if there are declines this year, whether they will stick or be an aberration.”

Although the United States has had teacher shortages for decades, the pandemic worsened them, according to the Learning Policy Institute, a nonprofit education research organization. Many teachers, tired of online teaching or disillusioned with disruptive student behavior, which escalated after schools reopened, quit or retired early.

A Rand Corp. study last year found that nearly all school districts had to combine or cancel classes, or asked teachers to take on additional duties in one or more of their schools because of the teacher shortage.

Konocti Unified Assistant Superintendent Chris Schoeneman isn’t surprised by the report. He traveled to 14 job fairs in California, Nevada and Montana this year to search for teachers and only managed to hire one. He still needs 36 teachers next school year, almost double the number of previous years.

“The system doesn’t have enough people in it,” he said. “This year we had to pay teachers to take on two classes and give them para(educator) support. They were teaching 50 or 60 at a time, instead of 20 or 30. Subs are hard to find, and we burn through the subs.”

Job fairs that once drew more than 100 candidates now are drawing just 20 or 30, he said. Schoeneman found the single candidate in Montana.

He attributes the lack of interest in teaching to change in student discipline policies and an increasingly difficult work environment for teachers.

“You hear that the kids are out of control. They aren’t, but we have fewer and fewer tools to deal with bad behavior,” Schoeneman said. “It’s a challenge.”

Recruiting teachers to Konocti Unified, a district serving 6,700 students in rural Lake County, more than an hour north of Santa Rosa, is already difficult. So, Konocti is recruiting new college graduates to work as interns at the district. Interns earn a full-time teacher’s salary while completing coursework and other training to become credentialed.

Nearly half the 184 teachers at Konocti Unified have less than five years of experience and 27% are working on intern or emergency-style permits without a preliminary or clear teaching credential, according to Schoeneman.

The number of emergency-style permits issued in California went up in 2021-22, as the number of teacher credentials went down, signaling an increase of underprepared teachers entering the workforce.

California issued 4,065 provisional intern permits and short-term staff permits — 28% more in 2021-22 than the previous year, according to the report by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing. School districts can ask the state to issue these permits to individuals who have not completed, or, in some cases, even started, teacher training, to fill an immediate staffing or anticipated staffing need. California also issued 5,812 new intern credentials that year — slightly more than the year before.

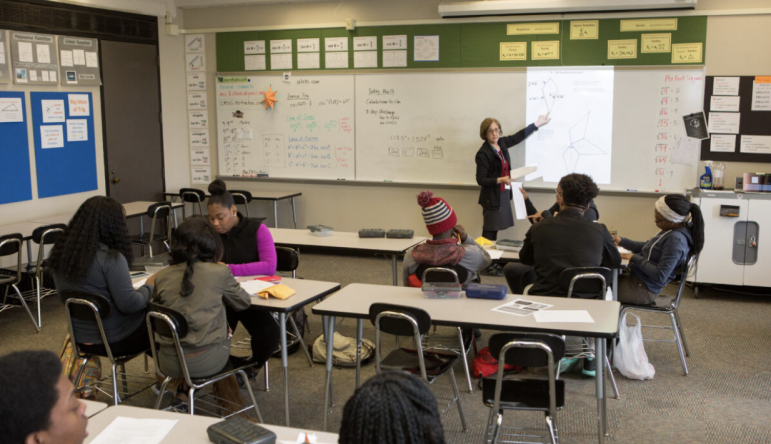

“We know that students of color, especially those who experience poverty, are disproportionately likely to have underprepared teachers and, in some cases, a string of substitutes if they don’t have fully prepared teachers to staff classrooms,” Luft said. “It has a significant impact on the outcomes of these students.”

Only the number of people issued a teaching waiver, which allows teachers to teach courses outside their credential when districts can’t find teachers with the appropriate credential, declined in 2021-22, compared with the previous year.

Districts have struggled to find teachers for hard-to-fill jobs like special education, science, math, and bilingual education for years. The lack of new candidates is making those shortages worse.

Finding bilingual teachers with bilingual authorizations — a specialized credential required to teach English language learners — has become increasingly difficult.

“Districts that want to expand bilingual programs, including dual-immersion programs, are limited because of the lack of staff,” said Manuel Buenrostro, associate director of policy for California Together. “Despite a demand for these programs, we won’t be able to meet the demand unless we meet bilingual teachers’ needs.”

California has been one of the few states gaining enrollment in teacher preparation programs, said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the State Board of Education in a March interview.

The state’s preparation programs added nearly 4,000 students between 2016 and 2021. It’s unclear whether enrollment gains continued in the 2021-22 school year as that data has yet to be released.

According to the commission report, teaching credentials issued to candidates prepared by California institutions of higher education in 2021-22 declined by 25% over the previous year.

Enrollment in California State University teacher preparation programs, which educate a majority of the state’s teachers, continues to be substantially below the 19,235 students enrolled 20 years ago.

The decline in the number of applications for teaching credentials may be tied to the expiration of state COVID flexibilities like waivers for both the California Basic Skills Test and the subject-matter competency requirement before teaching, said Cheryl Cotton, a deputy superintendent at the California Department of Education.

“We are back to pre-pandemic levels, back to issuing about 12,000 credentials each year,” Cotton said.

California has spent $1.2 billion since 2016 on programs meant to address teacher shortages. Among the largest expenditures is $515 million for the Golden State Teacher Grant program, $401 million for the Teacher Residency Grant program, and $170 million for the California Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing program, all of which offer teacher candidates financial support, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The proposed revised state budget for the upcoming fiscal year includes additional funding and flexibilities to help recruit and train teachers, including making it easier for members of the military and their spouses to transfer their teaching credential from another state, offering teachers other avenues to completing some tests if they were impacted by the COVID pandemic, increasing grants for teacher residents and funding a program to prepare bilingual teachers.

Cotton is hopeful the number of new teaching credentials will increase, especially with the state’s ongoing recruitment and retention efforts.

“It takes a while to turn things around,” Cotton said. “We’re hoping to see increases.”

Schoeneman would like the state to allow teachers to earn their bachelor’s degree and complete teacher preparation in four years instead of five, reduce the number of tests required to earn a credential, and offer teachers more autonomy once they are in the classroom.

To attract a diverse teacher workforce, the state should increase educator pay; encourage the building of affordable housing; facilitate partnerships to support teacher preparation and training; provide stipends to promising high school and college students who commit to working in the district; and help districts cultivate inclusive, culturally affirming and anti-racist school communities, according to the recently released “California Educator Diversity Roadmap,” a project of Californians for Justice, The Education Trust-West, and Public Advocates.

One of the recommendations made by focus groups that participated in the study was to pay teacher candidates who are completing their required student teaching hours.

“We also heard a bold call for something like a GI bill for teachers,” Luft said. “You shouldn’t have to pay for your education to become a teacher. The Golden State teacher Grant is a good start, but it isn’t enough.”

The Golden State Teacher Grant awards up to $20,000 to students enrolled in state-approved teacher preparation programs.

Konocti isn’t waiting for the state to sweeten the pot for teachers. The district is offering a $5,000 signing bonus for all newly hired teachers with a preliminary or clear credential and has opened a day care center that is subsidized for employees.

“We are trying to think of things to support young families and younger teachers,” he said. “Cutting day care costs in half is huge.”

The prolonged teacher shortage has the state and school district leaders looking to their high schools for future teachers.

In 2022, state legislators passed the California Golden State Pathways Program Grant Act to provide funds to school districts to promote careers in high-growth occupations like teaching. The program helps students “to move seamlessly from high school to college and career,” according to the California Department of Education website.

In Konocti, school staff promote the teaching profession in their high schools, hire graduates as paraeducators and in other district jobs, and encourage their former students to sign up as teaching interns.

“We talk about it all the time,” Schoeneman said. “If you see someone that has some talent, we are all over them on this. ‘You need to do this. You are really good at this. Here’s your pathway. You have to do it.’”