Many teenagers who’ve spent time in California’s juvenile detention facilities get high school diplomas with grade-school reading skills.

During a five-year span beginning in 2018, 85% of these students who graduated from high school and took a 12th-grade reading assessment did not pass it, according to data from the Division of Juvenile Justice, the agency operating state youth facilities.

What’s more, over a fifth of all students tested at lower grade levels, signaling how far behind these students are. And not a single student during those five years was below eighth grade, yet nearly a third of all assessments were for grades K-6, data show.

“You have kids getting their high school diplomas who aren’t able to even read and write, and that to me is a tragedy,” said Crystal Anthony, co-founder of Underground Grit, which helps youth in Orange County as they leave facilities.

The average age of DJJ youth is 19, but they can range from 14 to 25. And while the majority are boys and young men, these numbers also include girls and young women.

Being awarded a high school diploma while lacking grade-level reading skills is not a new phenomenon in California’s juvenile justice system. Los Angeles County was sued for it in 2010. This reading lag exists in both state and county youth facilities, officials confirmed. Experts indicate the issue is multifaceted, including an online credit recovery system that has drawn criticism for allowing students to earn fewer than 160 credits to graduate, incomplete assessment data, and prison-like facilities that house youths for varying periods.

Anthony and five others interviewed statewide for this story expressed frustration with the disconnect between graduation and low reading skills. The lament was repeated throughout the system from the juvenile justice program’s new director to researchers, social workers and youth educators.

For years, Adam Solorzano was caught in a cycle of drugs and arrest. Growing up in agricultural Westmorland, in Southern California’s Imperial County, he stopped attending school regularly in middle school and was addicted to drugs by 15. He was in and out of county jails on drug charges until about age 21.

Eventually, following a friend’s suggestion, he got his high school diploma at a local adult school. “I went from being a high school dropout and feeling like I wasn’t going to amount to anything, and then getting my high school diploma at 22 — but nothing changed,” said Solorzano. Like a crucial fact: He read at a sixth grade level, and at no point during his time cycling through the juvenile justice system, public schools, or the adult school were his low literacy skills addressed.

It all changed when he enrolled in Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District. Even enrolling was a hurdle: He didn’t read well enough to complete the online forms. Months later, he finally worked up the courage to ask for help. “She hit a couple of buttons, and I was a student,” he said.

It was only then, at age 25, that he was advised to enroll in remedial English, writing, and math — courses that he progressed through so quickly that he was soon offered a job tutoring other beginning students.

Some family members questioned his academic pursuits, but he pushed forward, eventually connecting with Underground Scholars, an organization that supports students navigating higher education post-incarceration.

Today, Solorzano is 30 and enrolled in the journalism graduate program at the University of California Berkeley, where he earned his undergraduate degree in comparative literature. “It’s been a long journey,” said Solorzano, referring to his academic experience as “crazy” for taking him to UC Berkeley, a college he had never heard of.

His story is not uncommon, according to experts.

Katherine Lucero, director of the Office of Youth and Community Restoration, the new state office leading the juvenile justice system, knows the challenges. “One of the things we want to know from each facility is: If it’s discovered a youth can’t read, are there resources to help them read?” she said.

“It’s horrible that a young person has to be incarcerated for any amount of time — but if it happens that a judge commits a youth for multiple years, shame on us if we haven’t done everything we can to have that youth leave with as much education as they could possibly desire.”

Students at DJJ facilities who have not completed high school read on average at a sixth-grade level, according to Lucero, quoting data reported to her by the state.

Kim Rigg, superintendent of education for the Division of Juvenile Justice schools, acknowledged that despite an average minimum stay of two years, youth rarely improve to their grade level. “One to three grade year improvement is typical,” Rigg wrote in an email.

“The reality is that we do get a lot of troubled youth that were not in the best situation socially, and it impacted them academically,” she said. “DJJ youth are sensitive to incentives, and generally not motivated to score well on standardized tests for which there is no reward.”

Another problem is the sketchy test score data. Education data for incarcerated students is generally difficult to access, in part due to privacy concerns, incomplete data entry and a lack of assessments created for the needs of incarcerated students.

The focus on the reading education of incarcerated youth comes at a critical time for California, which in July is shifting the operation of youth facilities from the state to the counties. Youths in state facilities will be assigned to one of 36 newly designated secure units inside existing juvenile facilities across the state’s 56 counties.

While officials say education is a priority, details are not outlined in the state law mandating the change or in the plans for the switch. In the end, each county office of education will decide how the curriculum for youths will meet the state’s education requirements.

“As the Office of Youth and Community Restoration guides the state’s transition to county-led youth justice, improving educational outcomes for youth is a top priority,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. “When youth have access to educational opportunities, they are better prepared for a successful transition into adulthood. OYCR is optimistic about counties’ efforts to improve educational outcomes for youth who are court-involved, and will continue to share best practices, resources, and technical assistance in support of those goals.”

The transition of incarcerated youth education to the counties also comes at a time when parents and teachers nationwide and in California are demanding a focus for all students on improving low test scores by embracing phonics and “the science of reading.”

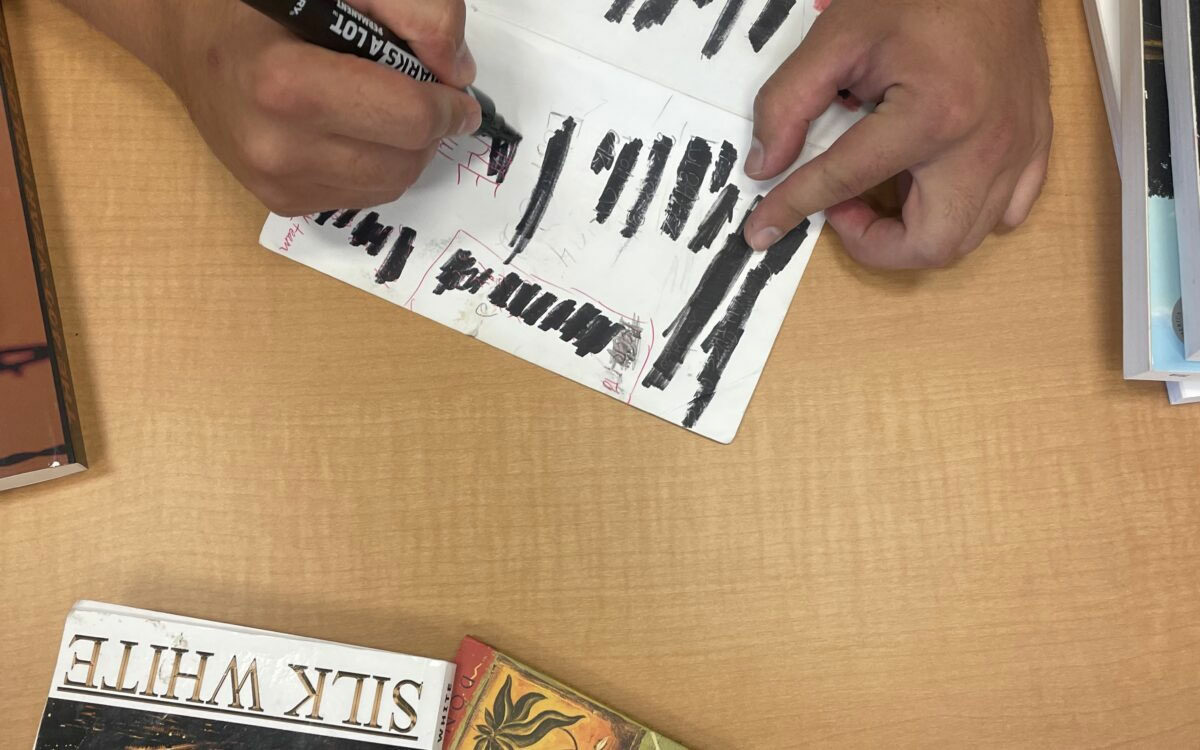

At DJJ, which has operated high schools inside four juvenile facilities, educators have relied on phonics assessments plus structured literacy programs, such as the Wilson Just Words Reading Program. County curriculums vary, though Los Angeles County offers an example: It relies on two programs, Read 180 and System44, which focus on phonemic awareness, phonics, reading comprehension and decoding through systematic, explicit instruction and individualized practice.

In the juvenile justice system, warnings that youth lack reading skills date back decades.

A 1978 national study found that more than a third of youth in the justice system were reading below the fourth-grade level. Other statistics have shown that 85% of youth in the country’s justice system have difficulty reading and that about 40% of 10th grade students in the system read below a fourth-grade level.

“Considering that reading competence is a critical factor for academic success … providing intensive reading instruction to detained and incarcerated youth has the potential to improve a successful return to school after release and reduce the likelihood to re-offend,” wrote the authors of a 2013 study that found race, age and learning disabilities play a significant role in incarcerated students’ reading skills.

A 2010 class-action lawsuit revealed that some Los Angeles County youths were granted diplomas despite being illiterate. A settlement resulted in the county implementing reading assessments and intervention programs, among other reforms.

Currently, youth typically arrive with a fourth-grade reading level, according to Diana Velasquez, executive director for educational programs at the L.A. County Office of Education.

Students receive a reading assessment upon arrival and then every 90 days. Those testing below grade level are assigned a literacy specialist for daily one-to-one work.

Yet, some say the juvenile justice system’s credit recovery program, in part implemented due to the settlement, incentivized youth to avoid taking catch-up classes that may increase their reading skills because they are excited about the prospect of graduating faster. This process, signed into law in Assembly Bill 216 in 2016, allows certain youth — such as those who are incarcerated, in foster care, or newly immigrated — to graduate with fewer academic credits. The bill’s intent is to remove graduation barriers for youth with unstable access to education.

“I understand the intent … but those are the kids who have left this place without knowing how to read,” said Florence Avognon, an educator in L.A. County juvenile facilities.

Velasquez said her team works to ensure that students do not leave without knowing how to read, even if they graduate with fewer credits.

“There were some safeguards that needed to be placed at the advent of AB216 as students were being provided that opportunity for graduation,” said Velasquez. “And for us, that … became really looking at those test scores before saying we’re signing off on a diploma.”

An analysis of L.A. County’s reading assessment data shows that checking for reading proficiency did not occur countywide, however. Many students did not get the initial assessment or the follow-up within the required times, according to a recent study from the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools.

The data also uncovered unexplained patterns in students’ reading ability. Some students first tested at a second grade reading level and improved to 11th grade by the second test, or vice versa.

“That’s a massive difference, which tells you that the kid was traumatized as hell when they came in, or resistant and didn’t want to do it,” said Angela James, director of research at the center and lead author of the study.

The dramatic changes suggest they’re negatively impacted by learning in a prisonlike environment, she said. The cases where this happened weren’t the norm, but there were enough to move the data averages.

“The fact of the matter is, the kids that are incarcerated are in a very traumatic circumstance,” said James. “Most of them have unmet educational needs before they arrive.”

California incarcerated over 4,100 youth in 2019. While the rate of youth incarceration has declined in recent decades, the number of Black and Latino youth remains disproportionately high, accounting for roughly 90% of the population. Between 30% and 35% of youth in state facilities are “designated special education,” according to the DJJ. About 95% of all incarcerated youth are boys and young men.

In 2017, the DJJ reported that 74.2% of youth released during the 2012-13 fiscal year were re-arrested, over 50% were convicted for new offenses, and nearly 40% returned to state custody within three years of release from a DJJ facility.

Access to education has long been established as crucial to lowering recidivism rates — by 43%, according to a 2013 study that conducted a comprehensive analysis of studies on the subject released during a 31-year period starting in 1980.

“It will be our responsibility at the end of the day to say: Did we do a good job? And we can no longer blame DJJ for that recidivism rate,” said Lucero.

While the shift of responsibility for incarcerated youth from the state to the counties is meant to reform the justice system, some advocates say they are concerned it won’t address access to accurate education data or the need for increased focus on high-quality education. It’s a concern that Lucero, director of the state agency, says is being prioritized.

“That’s why it’s even more important for counties to care about this, because there’s not going to be any place really to hide and to pass the buck to and to say it’s somebody else’s job,” she said. “What I do know for sure is government-trained folks are going to be raising these kids, so we have to make this a priority.”