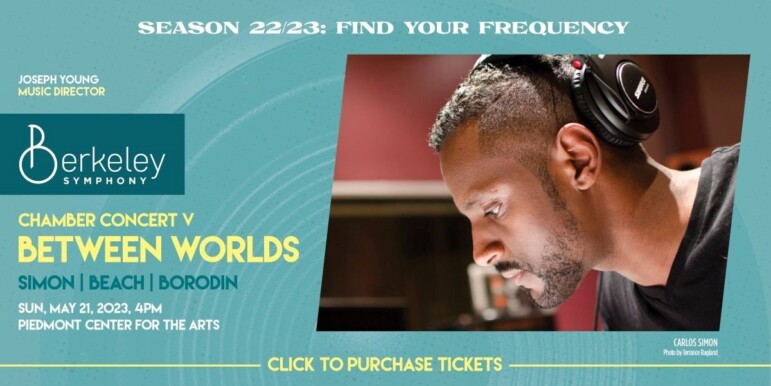

The Berkeley Symphony’s fifth and final chamber concert of this year’s season at the Piedmont Center for the Arts brings forth a powerhouse of composers with classical and contemporary works by Amy Beach, Alexander Borodin, and Carlos Simon. Entitled “Between Worlds,” the program expresses the diversity of musical approaches to individual identity and collective cultures while evoking bonds that span past and present.

Featured chamber artists include Stephanie Bibbo, violin; Emanuela Nikiforova, violin; Ivo Bokulic, viola; Stacey Pelinka, flute; and Elaine Kreston, cello. Between Worlds begins with Simon’s “move it,” for solo flute, followed by Beach’s “Theme and Variation for flute and string quartet, Op. 80.” Next comes Simon’s “Between Worlds,” performed by a solo violin, and Alexander Borodin’s “String Quartet No. 2.”

In an interview, Bulgarian violinist Nikiforova says this will be her first performance of a piece by Beach. Delighted by the work’s romantic, emotional, nostalgic sound, Nikiforova is equally enthusiastic about the challenges the score provides.

“It’s highly chromatic, with a dense texture and chords that are clustered. That makes it harder for an ensemble, because it’s not easy to hear the chromatic harmonies. But that’s good, because it makes you listen more carefully.”

Beach uses a key signature that’s unusual for string instruments, a signature with six sharps. When a certain note is played and there is an open string of the same note, it creates a more brilliant, resonant sound. Nikiforova says, “A lot of composers use that open sound. With this work by Beach, the more accidentals she put in — it makes for a different color. Even one of the scherzo parts stays within that same not-too-bright feeling and more muted sound. This is just for one variation and is a character she might have been looking to create for that one scherzo as the others are more lively.”

Bibbo was equally enthusiastic about how Simon’s “Between Worlds” violin solo uses the instrument’s full range. “From double stops to quick jumps between registers, the left hand very actively crawls up and down the fingerboard. This piece absolutely displays what the violin is capable of, and it has been a joy to have the opportunity to play it.”

Simon’s piece, like the overall program, is broad-ranging. The opening notes suggest a cry of sorrow or hopelessness, while the score indicates later passages are to be played “ferociously” and “defiantly,” Bibbo notes. The piece then spins into a whirlwind of triplet patterns that continue to the final notes. “The patterns vary in nature from having a groove to almost sounding nonsensical as they fly by,” says Bibbo. “I love how Simon weaves in and out of each section, creating moments of dance, chaos, searching, and ultimately, an undeniable, fiery ending. These dynamic aspects of the piece are what makes it very challenging!”

The concert closes with one of Borodin’s best-known, most-loved works. Popular with audiences in part due to the sweet melody listeners first hear in a conversation between the cello and the first violin, Nikiforova says the string quartet is “loving and caressing.” The melodic content streams throughout the work with little alteration other than key signature; instead finding variation by accompanying the recognizable melody with different accompaniment. By passing the material from one instrument to the next, the work’s richness is enhanced and the expressive, sentimental qualities are highlighted—something much needed, according to Nikiforova.

“I find that in modern days, life is so intense. To find a moment of sweetness, wherever it is, is special. In the current playing culture, with larger performance halls, people are looking for big sound, works with bite. But there’s something to be said about the softness of the Borodin that comes from the language of the culture where the music is written. The Russian language is not harsh, it’s sweet sounding. Often, Russian markings in a score tend to give way to sweeter, more expressive sound. Because Russian history comes from Peter the Great wanting to Westernize the Russian culture, he copied French style elegance, lightness, and finesse that you can hear in the Borodin.”

Nikiforova remarks in a follow-up email that it is difficult to talk about Russian history and culture now, in light of the country’s invasion of and war with Ukraine. Even so, she suggests Piedmont audiences are cultured, broadly educated, and always receptive to the music and historical context provided by the musicians at chamber concerts. “The Piedmont center has an established audience that is always ready to perceive and experience everything we offer. It’s lovely to play there, with very, very good acoustics and people eager to hear music. I hope the series continues for years to come.”

Between Worlds

- Sunday, May 21 at 4 p.m.

- Piedmont Center for the Arts | 801 Magnolia Ave.

- Get tickets HERE