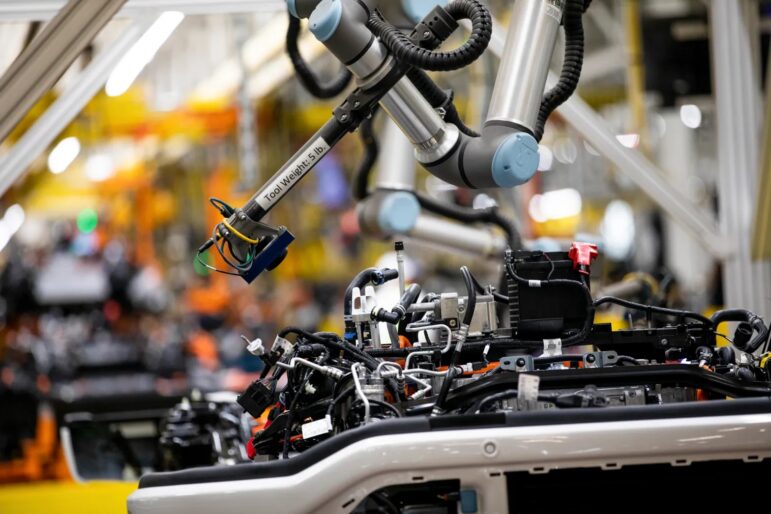

Amid the clank and clatter of the factory floor in Dearborn, Michigan, self-moving robotic vehicles transport the 1,600-pound batteries that power Ford’s flagship electric pickup truck to workers in various stations, who rush to bolt them to other parts.

After workers inspect each battery, the robot moves it along a track to the next station, then wedges itselfbetween two idling robotic arms. One arm is overhead, dangling the 2023 F-150 Lightning’s chassis, while the other swiftly moves to pick up the massive battery and attach it to the chassis.

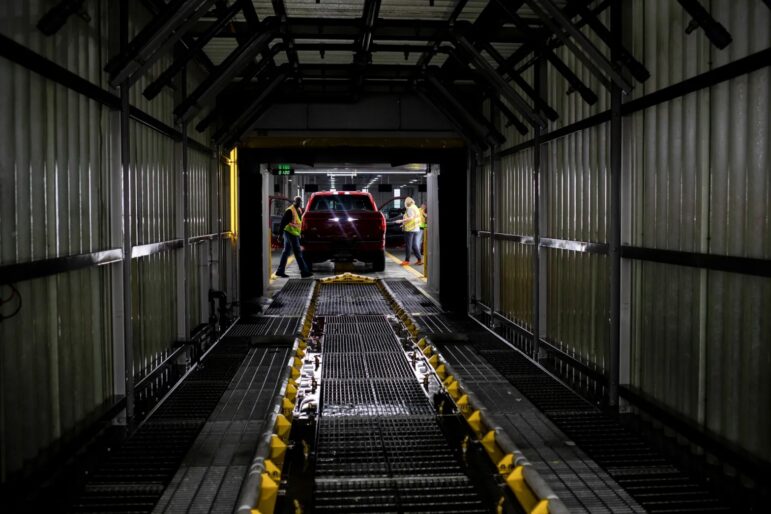

Assisted by more robots, workers quickly assemble the remaining parts: the aluminum frame, tires, cab and truck bed. Then the completed pickup truck — which has a long wait list of potential buyers — undergoes a final round of inspections and testing here at Ford’s Rouge Electric Vehicle Center.

From Michigan to Georgia to the Bay Area to overseas, a new age of car manufacturing has arrived, spurred by California’s landmark mandate to end new sales of gasoline-powered cars in a dozen years. Already the transition to electric vehicles is exposing automakers to myriad challenges as they rush to ramp up production.

“Demand for electric cars is rising even faster than ever before,” said Darren Palmer, Ford’s vice president of electric vehicle programs. “It’s changed the way we work, it’s changed everything.”

The industry is grappling with supply chain constraints, fierce competition for crucial raw battery materials, and a rush to start producing cheaper, U.S.-made batteries — while also getting new assembly plants up and running in time to meet California’s ambitious timeline. At the same time, the autoworker union has raised fears about job security and workplace safety during the industry’s rapid transformation.

Forty-four major factories already produce electric vehicles in the United States, and several automakers, including Toyota, Hyundai and Ford, are now building massive new factories to assemble electric cars, as well as new battery manufacturing plants. The investment in new U.S. factories: more than $40 billion.

Tesla has long-dominated the market, selling more than a million cars last year. Still, some companies, particularly Toyota — which sold only a few hundred all-electric cars in the U.S. last year and recalled them for faulty wheels — have been resistant and slow to make the change, industry experts say. Instead, Toyota remains focused on its hybrids instead.

At Ford, Palmer says they’re up to the task. By the end of this year, the automaker plans to produce at least 150,000 F-150 Lightningsa year — more than four times the number the company initially planned.

Facing California’s mandate, “we know that we will move to all-electric eventually — we’re all-in,” Palmer said, adding that “there’s a whole load of states that are all following California.”

“A challenge for a company like ours,” he said, “is how do you manage that transition?”

Revamping assembly lines — and the workforce

As one of the Big Three U.S. automakers, the Ford Motor Company has been a leader in the auto market since the company was founded more than a century ago, producing many of the gas-guzzling cars Americans love to drive. But California is now forcing Ford and the rest of the global auto industry to move quickly to zero-emission models.

Vehicles account for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions in California, making them the state’s single largest source warming the planet and polluting the air with smog and soot.

Adopted by the Air Resources Board last August, California’s mandate requires 35% of new 2026 cars sold in the state to be zero-emissions — almost double the current sales — then ramping up to 68% in 2030 until reaching 100% in 2035.

California drives the U.S. auto market — one out of every 10 cars is sold there — and at least 17 other states have pledged to enact California’s rules.

Putting even more pressure on automakers, the Biden administration last month followed California’s lead in proposing its own stringent measures to scale up production of electric vehicles nationwide.

Automakers will have to sell almost 12 million electric cars in California by 2035. Only about 838,000 electric vehicles were on California’s roads in 2021.

Such a rapid transformation of the giant industry is unprecedented.

“We just don’t have the production capacity today to satisfy that potential need in the future,” said Erich Muehlegger, a UC Davis professor of economics who analyzes electric vehicle market trends. “Automakers are in the process of developing that, but it’s not something that can be done overnight.”

During California’s rulemaking last year, the auto industry pushed for looser requirements, calling them “too aggressive” and “extremely challenging.” But now, as the state’s deadlines loom, many automakers are focusing their engineering skills and investments on achieving them.

State air-quality officials say they are confident that manufacturers can scale up to meet the deadlines. California is already two years ahead of schedule in achieving its 2025 target of selling 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles. About 19% of new cars in California last year were emissions-free.

“Now we are moving all the way to zero,” said Air Resources Board Chair Liane Randolph. “We’re very optimistic that we are going to see dramatically increasing deployment going forward.”

Ford announced a surge in its investments in electric vehicle production: about $50 billion globally for electric vehicles and battery materials through 2026 — up from $30 billion — with a goal of producing 2 million electric vehicles.

But to manufacture electric cars and pickups, Ford has to totally revamp its assembly lines and retrain its workforce. It’s a vastly different process than building a truck with an internal combustion engine. The all-electric version of the Ford F-150 pickup truck has far fewer parts than its gasoline-powered counterpart: no spark plugs, pistons, fuel tank, oil filter, multi-speed transmission, timing belt, muffler or catalytic converter — to mention only a few. Internal combustion engines have thousands of parts while electric power systems have only six main components.

The union representing General Motors, Ford and Chrysler workers says the transition could threaten job security. United Auto Workers estimated in 2018 that electrification could result in a loss of about 35,000 jobs among its 400,000 members.

For instance, the traditional, gas-powered model of the F-150 is assembled by 4,400 workers at Ford’s Dearborn factory, while the all-electric version, assembled next door, takes only about one-sixth of the workforce, 750 employees.

Laura Dickerson, director of United Auto Workers Region 1 in Michigan, said maintaining good-paying, middle class jobs will be critical to ensuring a successful transition to electric vehicles. Dickerson said workers who build cars don’t enter the industry because they’re passionate about gas-powered engines or electric vehicles — they do it because the jobs provide financial security.

“Moving into the future, we just need to make sure that we protect the work because those are environmentally friendly jobs,” she said.

Ford representatives declined to address questions about employee retention or layoffs, but said the company would be hiring additional employees as it expands its electric vehicle center. Ford will reassign an 800-person crew this fall, moving them from the plant that builds traditional F-150s, and plans to hire 300 new employees this year. In all, the F-150 Lightning plant will employ about 1,800.

The struggle to maintain good-paying jobs while producing electric vehicles has already led to clashes between some automakers and their employees. At a GM plant in 2019, nearly 50,000 unionized employees went on strike during contract negotiations when the automaker announced plans to shut down some plants that produce gas-powered cars and shift to electric car production.

Volkswagen’s top executive also predicted job losses, saying building an electric car takes “30% less effort” than building an internal combustion engine.

Dickerson said auto workers have expressed additional concerns about potential health and safety issues from working with batteries.

Many materials are highly flammable and can be explosive, and exposure to hazardous metals such as lead can cause health problems, she said. Workers had to be trained to safely handle the materials, along with high-voltage electric connections.

“Working in manufacturing can be dangerous and with electric vehicles, some of those dangers — we’re unaware of,” Dickerson said.

Dickerson said some minor accidents have likely occurred, but so far she knows of no fatal or serious accidents. The biggest concerns, she said, are whether the handling of the metals could expose workers to health problems in the future.

“They don’t know if they’ll get burnt by something, they don’t know if something else will develop from that down the line, because all of this is new,” she added. “There are a lot of unknowns to it and so people are very nervous.”

In response to the union’s concerns, Ford spokesperson Kelli Felker said the company takes “the safety of our workforce very seriously. Our manufacturing processes are designed to keep our workforce safe.”

Investing billions in EV assembly plants

When the first all-electric F-150 Lightning was unveiled in a live-streamed event broadcast in New York’s Times Square and the Las Vegas strip, U.S. consumers rushed to buy the vehicle that Ford dubbed “the truck of the future.”

But the demand for the electric version of the nation’s most popular pickup far exceeded the supply, creating long wait lists: Ford received more than 200,000 reservations for the F-150 Lightning in late 2021, creating a three-year backlog — months before the first models were available for sale. Consumers bought more than 15,000 in the first six months it was sold in 2022, according to a January sales report.

So Ford responded with a big surge in production, announcing it will now make 150,000 electric trucks a year, five times more than initially planned. Ford says demand for 2023 F-150 Lightnings is still outstripping supply, but that new customers likely will be able to begin placing orders this month.

“The F-150 is the vehicle that built America, so we made it electric,” Palmer said. “As soon as we realized the demand that was going to come, we started increasing production. Now that normally takes years and years for most companies. But at Ford, that’s what we’re very good at.”

The electric vehicle portion of Ford’s massive, century-old Dearborn River Rouge complex, which one executive called a “cathedral of manufacturing,” is still expanding as pressure ramps up to produce more models.

Ford now sells three all-electric models in the U.S. — the F-150 Lightning, the E-Transit van and the Mustang Mach-e — and will start building another electric pickup truck, called Project T3, in 2025, at BlueOval City, a $5.6 billion, 3,600-acre vehicle and battery mega-factory under construction in Tennessee.

BlueOval City is Ford’s largest investment in electric vehicle production to date, expected to provide about 5,700 new jobs and have the capacity to churn out at least 500,000 electric vehicles annually, according to Ermal Faulkner, the project’s site director.

The factory project has faced delays due to weather, although construction is on schedule with plans to open the plant in 2025, he said. Some supply chain delays and battery problems have also disrupted Ford’s EV production. In February, a battery fire temporarily stalled production of the F-150 Lightning.

To stay competitive, GM is producing the F-150 Lightning’s biggest rival — the new Chevy Silverado EV, an all-electric version of its best-selling pickup truck expected to be released later this year. The4.5 million square foot factory near Detroit, which opened in 2021 and is expanding,also will manufacture GMC Hummer EVs and the self-driving electric Cruise Origin.

GM, which expects to produce a total of 600,000 electric vehicles a year, is the only major automaker that has pledged to stop selling gasoline-powered cars around the world by 2035.

The EV wars: Fierce competition for car buyers

Economists are increasingly seeing growing competition among U.S. and overseas automakers in the EV market. That includes everything from sourcing necessary battery materials to offering competitive pricing for new models. Last year, U.S. customers bought more than 800,000 all-electric vehicles, nearly doubling from 2021 and totaling about 6% all vehicle sales.

Competition remains fierce as legacy automakers try to catch up to Tesla, which still dominates the market with two-thirds of all electric vehicle sales and the nation’s two top-selling models. Tesla has car assembly plants in the East Bay city of Fremont, as well as in Texas, Germany and China, and has invested in a $6.2 billion lithium-ion battery cell gigafactory in Nevada, with $3.6 billion more expected.

In response to Tesla slashing its prices in January for some of its models by 20%, Ford reduced the price of its Mach-E by up to $5,900.

Still, Ford and other legacy automakers like GM continue to trail behind in sales, although in the first three months of the year, GM did outsell Ford in electric cars by nearly two-to-one.

Ford’s automotive engineers are trying to change that.

Just five miles from the electric vehicle manufacturing plant in Dearborn, teams of engineers behind the glassy, reflective exterior of Ford’s world headquarters are racing to design more efficient and lighter-weight batteries. Their mission: To reduce the high upfront price tag of its electric models.

They’re rethinking battery chemistry and the components they use to hold the battery. The new batteries are one of the most important technologies of the clean energy future, said Charles Poon, the company’s director of electrified systems engineering.

Ford’s new strategy involves creating alternatives to batteries made with expensive nickel, cobalt or manganese, which are in high demand.Instead, the automaker is developing new, cheaper technology to incorporate more batteries made of lithium-iron-phosphate. Both Tesla and VW have announced that it will be the go-to for their standard-range EVs in U.S. and European markets.

Ford also is trying to replace heavy materials in its 1,600-pound battery pack without compromising the power output. The goal is to make future batteries more energy-dense, lighter and cheaper, Poon said.

“We’re working on it super hard,” Poon said. “We have new hardware technology, chemistry design and battery cell design to increase overall acceptance.”

Poon said the new lithium-iron-phosphate batteries would be far less expensive, which will yield vehicles that are more affordable than existing models. Reducing battery costs is critical because the high cost of electric vehicles is a major barrier to consumers. The average price of an electric car as of February was $58,385 — about $9,600 more than the average car — although it dropped from about $65,000 last year. Lower-end fully electric cars start around $27,500.

Teaming with Chinese battery companies

Rob Williams, a maintenance and engineering manager at the Rouge Electric Vehicle Center, said battery production delays have been one of the assembly line’s biggest challenges.

Access to critical battery minerals poses significant barriers to meeting California’s EV requirements, said Muehlegger of UC Davis. Ford also had to halt production in 2022 due to a computer chip shortage, and he said the industry still hasn’t recovered from supply chain disruptions it faced during the pandemic.

“If we are moving very quickly toward a world in which a high fraction of the new car fleet is going to be electric vehicles and not conventional vehicles, there’s a tremendous amount of battery capacity that needs to be created,” he said.

“There will be a lot of pressure to innovate in this industry. But how quickly the industry is able to innovate — and how quickly the industry shifts away from battery technologies that it’s using now to two new battery technologies that we haven’t discovered yet — it’s hard to know.”

A big part of the reason the auto industry is experiencing supply chain problems is because many materials, including nickel, lithium and cobalt, come from China, which Muehlegger said has become very efficient in refining and producing batteries. There’s only one lithium mine in the United States, located in Nevada.

Switching to U.S.-made components is essential so car buyers can qualify for federal tax credits. For sales to qualify for credits of up to $7,500 in the Inflation Reduction Act, automakers must adhere to strict rules that call for most of its components to be produced or manufactured in the United States or its close trade partners.

Only 14 models qualify for the credit under rules released by the Biden administration in April. Ford’s F-150 Lightning is listed as one of the few qualifying trucks, but the vehicle’s high upfront price tag could make it ineligible for the federal incentives. Currently, Ford’s truck models range from $59,974 to $98,070; to qualify, cars must have a price tag below $55,000, and trucks or larger SUVs under $80,000.

Diversifying and building a new supply chain from scratch in U.S.-friendly countries could delay production, since it takes years to build up, said Muehlegger, of UC Davis.

That’s why Ford has partnered with a Chinese battery supplier, SK On, to build a new lithium-iron-phosphate battery plant in Michigan: By building its own batteries, Ford hopes to obtain a steady stream of materials.

Tesla, in a move to ensure its cars qualify for the consumer tax credit, is trying to secure a similar partnership with a Chinese company to build a lithium-iron-phosphate battery manufacturing plant in Texas.

Palmer, Ford’s vice president of electric vehicle programs, said the company has already secured 100% of the annual battery supply needed for 600,000 vehicles and 70% of the battery materials it needs for an annual global production rate of 2 million electric vehicles by 2026.

“If we hadn’t done this, if we waited two years to invest, we would be in such trouble to be able to secure the amount of materials needed,” Palmer said.

Part of Tesla’s dominating success has been building its own extensive charging network for its vehicles, said David Reichmuth, a senior engineer at the Union of Concerned Scientists’ clean transportation program. Other automakers should be prioritizing that, too, he said, because insufficient public chargers have been a huge barrier for renters, multi-family home residents and low-income residents.

“If they’re going to sell these vehicles,” Reichmuth said, “they need to make sure drivers have a positive experience.”