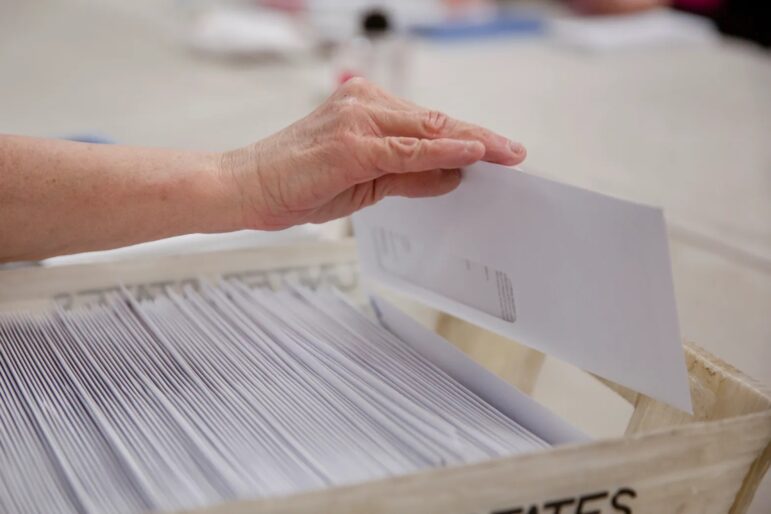

At a warehouse tucked into a suburban Bay Area office park, along white folding tables lined up like an assembly line, about 50 people on a March morning snapped together plastic pieces of bicycle safety mirrors or stuffed envelopes with a nonprofit’s donor letters.

The tasks were simple, but it’s work.

The laborers are all adults who have intellectual or developmental disabilities, performing jobs under contract for local businesses and nonprofits. VistAbility, the nonprofit employment services provider that runs the shop, pays them each $3 to $14 an hour, depending on their speed.

The arrangement is legal — for now.

Thanks to a 2021 law change, California will soon ban paying subminimum wages to people with disabilities, a decades-old practice originating from the Great Depression.

By 2025 “sheltered” disability programs like the one at VistAbility — which together employ about 5,000 Californians statewide — must begin paying the state’s $15.50-an-hour minimum wage or shut down.

The transition toward better pay has exposed a bitter debate within the state’s disability services community: Can everyone with a disability get a job in the broader labor market — and should that be the goal? And for a group of people largely receiving public assistance, what’s the role of a job in their lives?

John Bolle, VistAbility’s executive director, said when his workshop is required to pay minimum wage, some of the faster workers may be able keep working. But he doubts local businesses and nonprofits will pay more expensive contracts to accommodate higher wages, and he predicted those with the most significant disabilities likely will lose their jobs.

“The state is essentially ignoring those people,” he said.

At VistAbility some workers said they liked the company of coworkers, the steady tasks and guaranteed weekday hours. They said it would be harder to find an “outside job.” John Shillick, 61, said he used to clean motel rooms with the help of a job coach, but he found it difficult to keep pace.

“I would like to get a better job with a decent salary,” Shillick said. “I don’t know exactly what, but something within my reach.”

Opponents of sub-minimum wage programs like Vistability’s say they segregate people who have disabilities, keeping them from obtaining better paying work and greater independence — which they could achieve with the right services to assist them.

On the other side, program operators and some workers’ families defend the current arrangements, saying these workers would not otherwise have job opportunities. About 20% of people who have developmental disabilities in California are employed, the state’s Department of Developmental Services says.

Chris Bowers’ 42-year-old son, Cory, was one. He worked for nearly 20 years for less than minimum wage at an Orange County retail store, where an employment services provider placed him. Recently that provider shut down its sub-minimum wage programs, ending his job.

Now Bowers can’t imagine his son, who has Down syndrome, finding a job like that one, which provided transportation and a job coach.

“There’s no avenue for our kids to go to a job site, other than somebody’s going to have to pay them $16 an hour,” Bowers said. “He can’t do the job of somebody that’s earning $16 an hour. It’s just not going to happen.”

The new law requires that all subminimum wage workshops phase out. Whether their participants end up in better jobs, or with little to occupy their days, in large part depends on how California’s disability services system responds.

The Department of Developmental Services, which pays for these services, says it is ramping up funding so providers of job placement services can get those currently working for less than minimum wage into “competitive integrated employment” — that is, working for at least minimum wage alongside coworkers who don’t have disabilities.

But if the past is prologue, the Legislative Analyst Office notes such resources are under-utilized.

The office analyzed state-funded competitive integrated employment programs for workers with disabilities — including paid internships — and found that service providers used only 60% of the funds allocated in the 2021-2022 fiscal year. And that was the most spent in each of the last five years.

The developmental services department gave out $10 million in grants from last year’s budget to boost employment services and is developing another program this year to pay for placing workers with disabilities into competitive employment.

“We have to set a new direction for our entire system, where employment is the expectation for everyone,” said Brian Winfield, its director of programs.

But many worry that when workshops go away, there won’t be enough job placement services to go around. The disability services system is underfunded and understaffed, said Barry Jardini, director of the California Disability Services Association.

“A lot of the challenge is around whether or not we have the policies in place in California today to make it possible on a broad scale to provide the intensive (worker) supports and job discovery, job exploration,” Jardini said. “Right now all of this policy change is being overlaid on a very stressed system.”

There also is a lack of data. The state tracks the kinds of employment services these workers get, but not the kinds of jobs, so it’s unclear where people exiting workshops are landing.

Paying people with disabilities less than the minimum wage is legal because of a New Deal-era section of federal labor law called “14c,” designed to help wounded World War I veterans get limited access to jobs.

Employers registered with the federal government to hire these workers at a fraction of the pay of other workers. The employers assessed their productivity every six months, comparing them to non-disabled workers making market wages.

Now the vast majority of 14c employers in California are vocational rehabilitation providers — job training services for people who have intellectual or developmental disabilities, including autism, Down syndrome and cerebral palsy.

Californians with disabilities have a constitutional right to services that allow them to live as independently as possible. If they seek employment help, state regional disabilities centers can refer them to 14c programs or to other employment options.

Employers in 14c programs can pay workers less than not only the California minimum wage, but also the federal $7.25-an-hour minimum wage, in two types of settings: in congregate, factory-like worksites sometimes called “sheltered workshops,” or in small work groups that are assisted by a job coach. In the groups, three or four workers split a single minimum wage position, typically mopping floors or stocking shelves at a local business.

Subminimum wage positions are most suitable for those with the most significant disabilities, program operators said.

As part of the national shift toward integrating people with disabilities into communities, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2020 called for subminimum wage programs to end, saying the programs trap people in “exploitative and discriminatory” situations.

Michael Pugliese, who has autism, worked in a video rental store after high school but lost that job when the industry crashed.

When he was 21, a state regional center referred him to a sheltered workshop in the Sacramento area for employment training. At the workshop Pugliese assembled electronics alongside other workers with disabilities, cordoned off from other workers.

The job paid him about $225 a month, included little useful training for other work and made him feel like “a cog in a machine,” said Pugliese, now 37.

“I didn’t know at that point in time that was nickels and dimes,” he said of his pay, compared to coworkers’.

A dozen states besides California have passed laws banning below-minimum-wage programs. Also a federal rule in effect this year requires disability services to be more integrated with the community.

These kinds of jobs have already declined in California. In 2009, as many as 16,000 people with disabilities worked in the workshops or the small groups that split a minimum wage. By 2021, employment in those programs had fallen to about 6,000, state officials said.

Now that the phaseout deadline approaches, it’s up to the state and a network of disability service providers to help transition workshop employees into other jobs, if they want them.

The gold standard, according to the independent State Council on Developmental Disabilities, would be a job placement and coaching service that’s highly tailored to fit each worker’s needs and abilities.

Carole Watilo directs the Sacramento-area Progressive Employment Concepts, which provides job coaching and placement.

She said a client who uses a wheelchair and communicates using a tablet device handles code enforcement for a small police department in Sacramento County, including spotting such violations as people parking illegally in disabled spaces. A support worker drives him.

Progressive initially placed him there as a volunteer, she said, then it received grants to cover his work. She hopes to find him ongoing paid employment.

“When you start from the premise that there are going to be people that you can’t find a job for, then that is going to be a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Watilo said.

Pugliese also sought job services at Progressive after leaving the workshop. When he told them of his affinity for pets, a job coach found him a state-funded internship grooming dogs. They tried him at several pet groomers until they found a good fit.

He’s on a health leave now but normally earns $16 an hour.

“I’ve had more general impact on the actual shop than ever before,” he said. “My actual work effort was reflected in the shop’s progress. I mattered as a person and as an employee.”

Chris Bowers, Cory’s father, said he doubts his son will work the same jobs as everybody else. That’s just the reality of the job market, he said.

In high school Cory Bowers went to classes with a group of other students with disabilities. After they graduated, Goodwill of Orange County placed him, with two or three others, at a clothing company’s warehouse and later at a local retailer. They hung clothes on racks, splitting one minimum-wage job.

Corey took home $2.50 an hour, his father said. He loved his job and came home feeling accomplished and eager to spend his paycheck, taking his parents out to dinner, Chris Bowers said.

Goodwill of Orange County closed its subminimum wage program during the pandemic and never reopened it.

Before the pandemic, the nonprofit had placed as many as 700 workers in its stores or in local businesses, paying them less than minimum wage. Rick Adams, its vice president of mission services, said the “vast majority” of businesses were not interested in taking the workers back at higher wages.

Now about 100 people with disabilities work for Goodwill stores and 50 have jobs in the community, he said.

Instead of working, Cory now participates in a day services program that drives him and others to visit the library, coffee shops and stores. Chris Bowers described it as “glorified babysitting” and says his son is “different mentally.”

To Chris Bowers it was never about the money; his son lives with him and receives Social Security benefits.

“As parents, especially in my circle, we sure didn’t care what our kids made,” he said. “We just wanted our kids to be out in a job site, learning.”