California students are back in school, but many are still slow to return from the pandemic, forcing districts to try special strategies to bring students back.

Absenteeism for this school year appears to be a nagging problem, according to data collected by School Innovations & Achievement, a software company that contracts with districts to collect and analyze their attendance data.

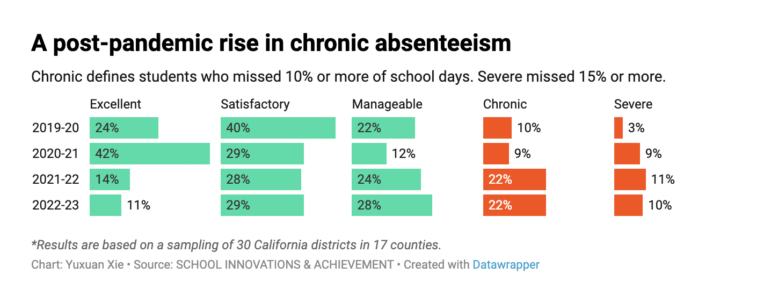

An analysis of 30 districts statewide, that the company says demographically represents the state, shows that nearly a third of public school students were chronically absent — meaning that as of late March, they had missed 10% or more of the school year. That’s slightly lower than the same point last year. Before the pandemic, only 13.5% of students were counted as chronically absent at that time of year.

School Innovations & Achievement declined to identify the districts included in the sample, citing student privacy. The sample has “all types of district configurations to reflect what is happening in districts across the state,” said Tony Wold, chief business officer in residence.

The company’s survey surfaced last week during a board meeting in West Contra Costa Unified School District in the East Bay. Officials pointed to the statewide data to show that the district’s chronic absentee rate of 33% this year tracks with what’s happening statewide. West Contra Costa’s absenteeism this year is also significantly higher than this time over each of the past two years.

Board member Leslie Reckler urged the West Contra Costa board to take the high absenteeism seriously given the connection between absenteeism and academic struggles.

“This is a hair-on-fire emergency, and we are not alone, it’s across the state,” Reckler told the board. “The data prove quite succinctly that if you don’t show up, you’re going to do worse, and it’s statistically correlated with lots of things like not graduating, not learning to read and not learning basic numeracy. It’s very serious, and we need all the help we can get.”

Research shows that students who are chronically absent are at the greatest risk of falling behind and dropping out of school. The issue has affected students who are low-income, students with disabilities, and English language learners. Black and Latino students have historically had higher absentee rates, trends that School Innovations & Achievement’s recent analysis confirmed.

Wold, who used to work as chief business officer for West Contra Costa Unified, said bringing attendance rates up to what they were before the pandemic will be a long, slow process, due to changed attitudes by students and families toward school. They value safety over attendance and are more likely to miss days out of fear that they could get sick, he said.

The firm’s analysis also shows that in addition to the rise in the number of chronically absent students, school attendance has failed to return to pre-pandemic levels. Average daily attendance has plummeted from 95.9% in 2019-20, before the pandemic, with the average student missing 7.38 days a year, to 91.01% in 2021-22, with the average student missing 16.18 days. For the first 30 days of the 2022-23 school year, average daily attendance was 92.5%, based on data from 100 districts.

Students in kindergarten and senior year of high school posted the highest rates of absenteeism in 2022 while grades nine through 11 showed drops.

It’s up to districts to be proactive about school attendance to restore the norm of missing as little of school as possible, said Wold. The company he represents charges districts to analyze their school attendance and share strategies for getting students to come to school and return to school. The company also contracts with the California Department of Education to provide status updates on attendance rates.

“I don’t think the old attendance rates will ever come back to the same, unless we create a whole different model because teaching has had to change and learning has had to change,” he said.

School Innovation & Achievement emphasizes the importance of consistent communications with families and the community at large about attendance, including targeted, positive messaging about the importance of coming to school. The company also encourages schools to analyze attendance data regularly in order to make course corrections to focus outreach efforts where needed.

The sample of 30 districts does not include Los Angeles Unified, the largest district in the state.

However, LAUSD Superintendent Alberto Carvalho has identified chronic absenteeism as a top concern. At the end of the 2021-22 school year, Los Angeles Unified’s chronic absenteeism rate was 45.2%, and in March of this year, 36% of students were chronically absent, according to an ABC News report citing district data obtained through public records request. Carvalho himself has knocked on doors to connect with parents whose children were truant.

LaShante Smith, West Contra Costa’s director of positive school climate, alerted the board that many of those absences are excused, meaning the child was called in sick but still count toward the state’s definition of chronically absent.

“We do notice this and have been serious about trying to reconnect and reengage with our families who are missing school,” Smith said. “We’ve put in place several different initiatives and partnered with several different organizations to support us in reaching our students who are not coming to school.”

The majority of students served by West Contra Costa Unified are Latino, representing 57.2% of enrollment in 2021-22, and Black, representing 12.7% of enrollment.

The district launched a campaign to build good attendance habits among TK-3 students, since West Contra Costa Unified and the state are seeing higher numbers of students in those grades consistently absent from school.

“We’re supporting parents to understand the importance of attending school every day, that even missing 10 minutes a day of school can add up over a school year, and re-educating our families to have a culture around attendance,” Smith said.

And when students continually miss school, the district takes other steps to involve the family.

The district conducts school site conferences with parents before a student goes to a school attendance review board hearing. The boards are set up in districts across the state to help address truancy, and typically they consist of officials in the district, the county office of education and other entities. The attendance board in West Contra Costa Unified puts students on an attendance improvement plan that addresses the barriers they are experiencing and monitors their attendance until they reach a satisfactory attendance level.

The district has lagged in getting students into the attendance review board process because the first step is a meeting with parents, and many do not attend. The district is trying to beef up its efforts to reach out to families, Smith said.

The district also contracts with providers to do home visits for truant students to uncover the root causes of poor attendance and address those barriers, Smith said.

“From the home visits, we’ve seen a lot of things come up around students getting jobs during the COVID time and now continuing to be employed and not able to attend school,” Smith said.

“We’ve seen families working two jobs, working double shifts and not being able to get their kids to school. So we’re trying to work with these families and work with the students to find out what alternatives we can put in place so that we can get our students in school.”

Smith said the district has seen more parents now than before the pandemic keep their students home if they have a minor cough or sneeze. Parents are also keeping their students home from school due to anxiety or mental health issues more often than before the pandemic.

From the student attendance review board meetings, the district is finding many instances where the barrier is transportation-related, Smith said, often due to a parent’s work preventing them from being able to get their student to school on time. The district has offered solutions such as giving bus passes out to students and families, helping parents arrange carpools, and even partnering with nonprofit fundraiser Ed Fund West to give out gas cards that parents can use or give to others to drive their students to school.

From the attendance review board meetings for older students, one of the main issues is that students are prioritizing working over high school.

“It’s students not really feeling a connection with school, or wanting to come to school, and feeling like working is a way to make money right now and a better outlet than coming to school,” Smith said.