For many, photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984) offers an introduction to the splendors of the American West, particularly Yosemite National Park, in all their rugged beauty. Adams’ unparalleled views of sequoia forests, soaring mountains and the moon illuminating them were products of his frequent trips to the area. He even scaled snow-covered cliffs, as a clip of a 1917 film at the beginning of “Ansel Adams in Our Time” reveals, to capture images he visualized in his mind’s eye before snapping the shutter.

“Ansel Adams in Our Time,” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco through July, is not simply an exhibition of the famed artist’s work. It also provides a visual dialogue with photographers who preceded him, and those who followed him in contemporary times who carried on his interest in the beauty of the West as well as in the environmental advocacy and ecological concerns he addressed.

This exhibition very much belongs at the de Young, where Adams—a San Francisco native who took pictures of Yosemite at age 14—had his first photography exhibition in 1932. And it was at a 1963 de Young exhibition of Adams’ work that William and Saundra Lane (whose collection of 450 Adams photographs was donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) first met Adams and began collecting his work.

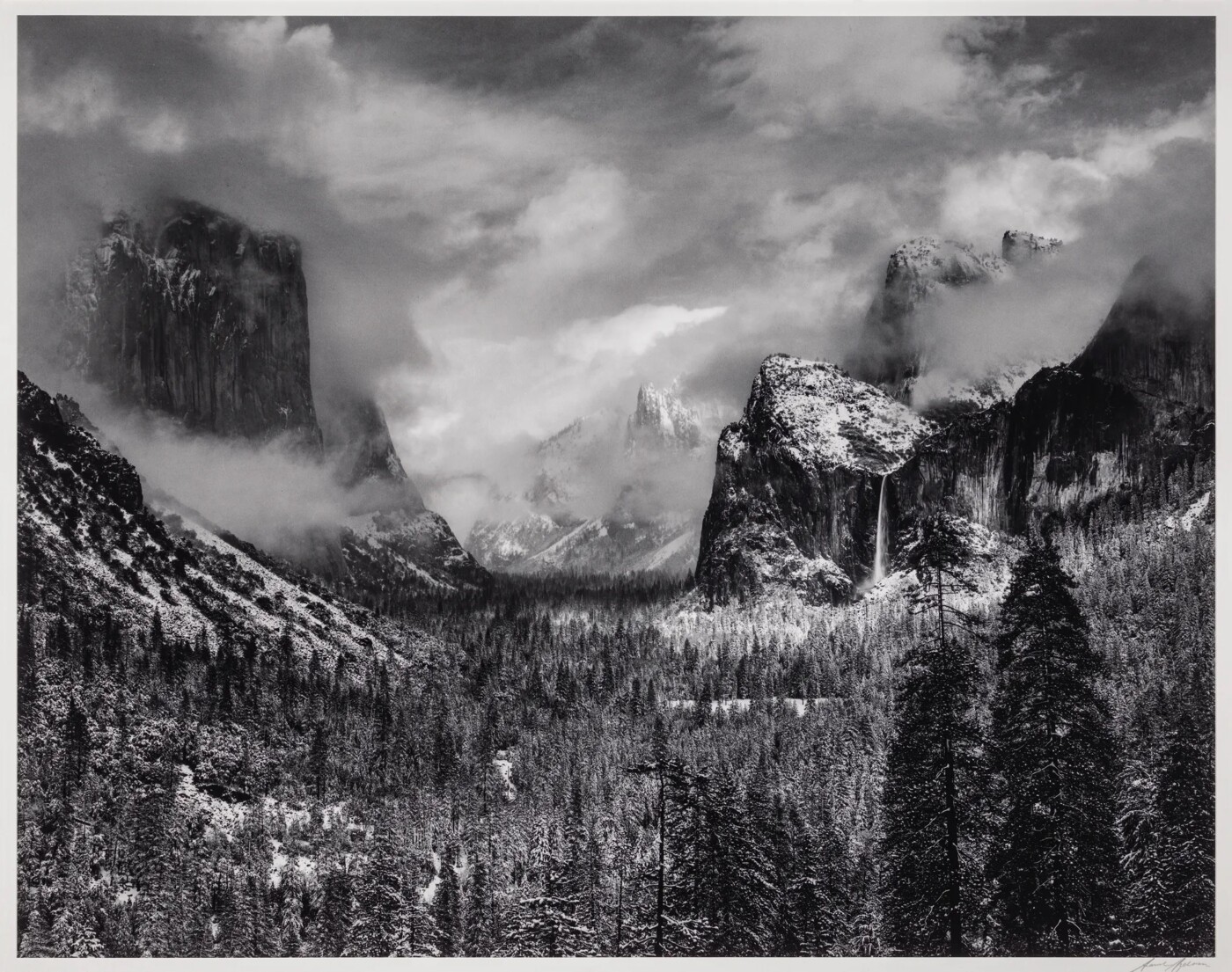

The Lanes’ gift was the genesis for the current exhibition, presented by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in partnership with the de Young. Featuring some of Adams’ photographs never on public view before, it consists of more than 100 of images, many of Yosemite and other national parks, including the 1927 groundbreaking “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome,” “Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite” (1937), “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” (1941) and the 1960 “Moon and Half Dome.”

But it also includes Adams’ lesser-known photographs: of his friend, Georgia O’Keeffe; of Pueblo ceremonies; of Taos, New Mexico; and of interlacing highways in Los Angeles. There’s an image of a serene religious statue against a background of oil derricks as well as Depression-era scenes reminiscent of those by Works Progress Administration photographers.

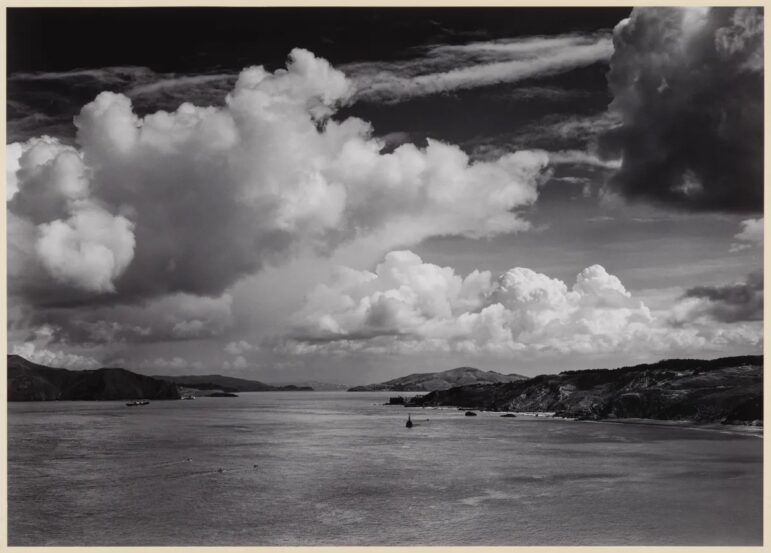

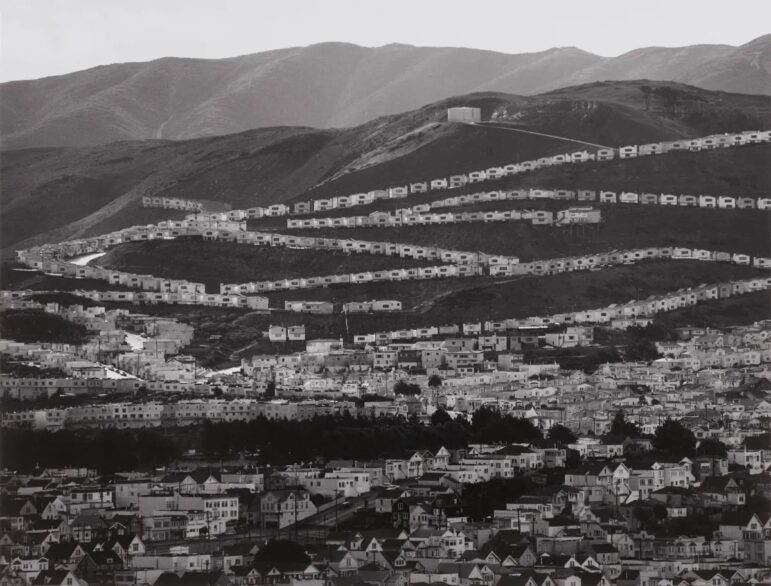

Also on view are photos taken by Adams in San Francisco over the years, including political posters, a “cigar store Indian,” a sprawling housing development blanketing a mountain, the interior of a downtown bathhouse, the remains of the Sutro Baths, and the Golden Gate before the bridge was built.

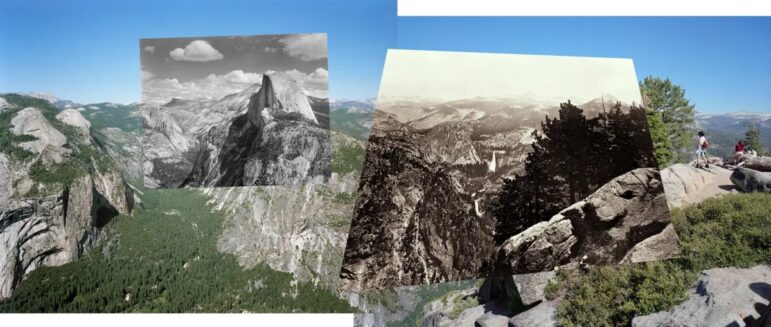

Among the exhibition’s particular pleasures are temporal links it forges between 19th century photographers (many of them government surveyors who preceded Adams in photographing the American West, including Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge), but also of contemporary photographers who reframed his scenes, providing modern views of locations he photographed and his environmental concerns.

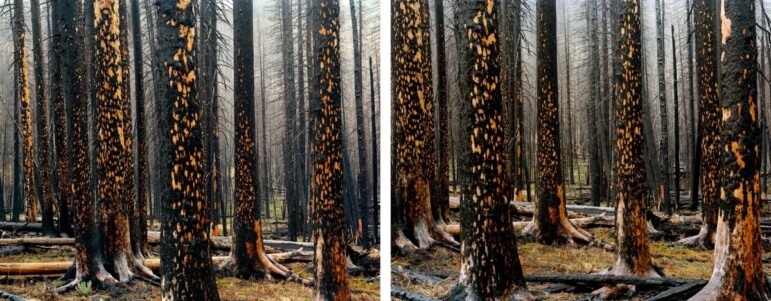

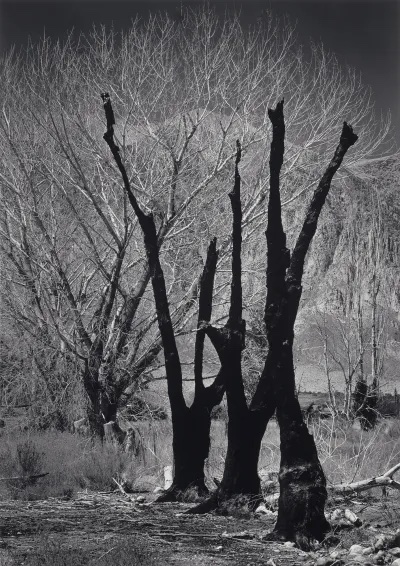

For example, Laura McPhee’s two large photographs (of a majestic forest severely burned and the same forest two years later, its floor covered with pink lupines, announcing the natural regeneration underway) hang adjacent to Adams’ view of a severely burned tree stump, some wisps of grass adjacent to it, its outer layer so desiccated, it resembles elephant skin.

Contemporary photographers Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe’s collages incorporate Watkins’ 19th century view of the area around Yosemite Falls and the Merced River with contemporary views of tourists boating, picnicking and hiking, reminding us that tourism has repurposed the wilderness experience.

Richard Misrach has four photographs of the Golden Gate Bridge, each shot from the same vantage point on his Berkeley porch, but at differing times of day. Misrach’s study of light riffs on Adams’ amazing use of light.

Abelardo Morell photographs the area surrounding the Rio Grande River as a scene of contested space and dislocation. Stephen Tourlentes photographs western super-prisons from a distance at night, revealing the alterations the penitentiary makes in natural space and light.

Contemporary photographer Will Wilson addresses indigenous identity, introduced in Adams’ work by his photographs of ceremonies and portraits. Wilson’s “When the West Is One” shows two divergent portraits of himself, one as a Western cowboy, the other as an indigenous inhabitant of North America, the two staring at each other.

“Ansel Adams in Our Time” continues through July 23 at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. Hours are 9:30 a.m. to 5:15 p.m. Tuesdays-Sundays. Tickets are $15 (youth) to $30 (general). Call (888) 901-6645, (415) 750-3600 or visit famsf.org.