Like so much else about California, its state government is large: A $300 billion budget. More than 230 departments and agencies. More than 234,000 employees.

Keeping the public apprised of everything that’s happening in that massive bureaucracy requires its own small army of communications staff, who craft messages, write press releases and answer questions from journalists covering everything from the governor to welfare programs, prisons to water policy.

Lately, however, the information isn’t flowing as freely — raising transparency concerns among the press corps that acts as a watchdog for Californians.

Last month, the Capitol Correspondents Association of California, which represents journalists who cover the state Capitol and advocates for improved press access, distributed guidelines to its members about how to handle some of the increasingly common hurdles they encounter, including government agencies asking for questions in advance and refusing to attribute information to their spokespeople.

Ashley Zavala, president of the correspondents association who covers state government and politics for Sacramento television station KCRA, said the extraordinary step was prompted by years of complaints from Capitol press about problems reporting on Gov. Gavin Newsom, his administration and the Legislature. These have been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, which accelerated a shift to digital communication that has transformed how the state government discloses its work.

“The pandemic did cause some bad behavior,” Zavala said. “It let some of these agencies and some of these offices get lackadaisical in how they handled the media.”

Many of the standard features of government beat reporting — including in-person press conferences, with an opportunity for follow-up questions, and media phone lines where journalists could talk to a live staffer — disappeared three years ago with the shutdown orders and have been slow to return, if at all.

Changes that reporters and public information officers adopted to do their jobs virtually in a strange new stay-at-home world became ingrained, encouraging practices, such as written statements instead of interviews, that offer less clarity and greater distance between state government and the people it serves.

This tension — between journalists seeking accountability and a bureaucracy that does not always welcome scrutiny — is not new. Covering state government has grown more difficult in recent years with fewer reporters covering the Capitol and social media offering politicians new ways to reach constituents and voters without speaking to the press. Those trends were exacerbated by restrictions applied during the pandemic.

The risk is a decline of “open, honest and transparent communication” essential to the functioning of democracy, said David Loy, legal director of the First Amendment Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for a free press and government disclosure.

Media outlets across the state note rejected interview requests, challenges obtaining public records or the lack of any official response in their stories:

- For a Los Angeles Times series over the past year about the broken promises of recreational cannabis legalization, the Department of Industrial Relations and the Department of Cannabis Control refused to provide information about complaints filed by exploited workers, ignored questions about delayed wage theft investigations and policies for handling allegations of labor trafficking, and sought to block the release of satellite imagery mapping illegal cultivations.

- On the Friday afternoon before the New Year’s holiday, the Department of Health Care Services sent out a notice walking back changes to its bidding process for insurers under Medi-Cal, the state’s health care program for poor people. A CalMatters reporter followed up with questions about why the department changed course, whether it was related to a possible lawsuit by insurance providers left out of the process and when patients would be notified. The department said its “statement speaks for itself” until after the holiday, but never responded when the reporter followed up.

- Sacramento television station KCRA aired a story last year about criminal groups skimming food benefits and welfare funds at ATMs, for which the Department of Social Services did not respond to questions about fraud prevention efforts.

- Ahead of the end of California’s COVID-19 state of emergency last month, a CalMatters reporter asked the Department of Public Health for an interview to discuss widening racial and ethnic gaps in vaccination rates and the state’s long-term strategy for managing the coronavirus. The department did not respond until after the story was published, in a written statement which acknowledged, “We know we missed your deadline, but hopefully this information is still useful and of value for you!”

- Multiple news outlets, including CalMatters and the Los Angeles Times, covered the Department of Education’s highly unusual rollout of long-delayed state test scores last October. It included holding a short briefing for reporters before providing them with any of the results and then releasing the data on a Sunday morning, embargoed for the next day, severely limiting their opportunity to reach school officials to discuss the scores before they became public. A department spokesperson said their timeline was constrained because they wanted to release the state scores alongside results from another federal exam.

- The Department of Public Health turned down numerous interview requests and often refused to answer specific questions for a series of stories in 2021 by CalMatters, online news site LAist and San Diego radio station KPBS about failures in state oversight of nursing home, including allowing a nursing assistant to stay on the job for more than three years after he was accused of sexually assaulting a patient.

“These message control practices do real harm to the public interest,” Loy said. “Because the people need to know the full story, not just the official story.”

No standard communications policy

There is no shortage of people responsible for the state government’s communication of public information: 435 employees in the executive branch, to be exact, according to a count conducted for CalMatters by the Department of Human Resources. An analysis of salary ranges based on job titles found that the annual cost to taxpayers is between $36.5 million and $44.8 million.

There are even more press aides working for other branches, such as the Legislature, the judiciary and public universities. The jobs of these communications officials extend beyond answering reporters’ questions and can include duties such as developing public relations strategies, writing speeches and managing social media accounts.

Yet, besides laws mandating open meetings and the release of public records, California does not have standards for appropriate public communications. Policies are at the discretion of those hundreds of individual agencies and departments.

A spokesperson for Newsom said his administration has not issued any directives for communication by state officials, either to standardize practices or to address problems raised by the press corps. State agencies are part of the governor’s administration and their leaders are gubernatorial appointees. In addition, there are seven departments or offices that are supervised by statewide elected officials, including the attorney general and the secretary of state.

But the governor’s office does get involved with the response to the most notable media inquiries and records requests.

“As is the case across all aspects of the administration, including communications, policy and legislation, there is an expectation that departments and agencies flag high profile issues for attention for the governor’s office,” spokesperson Anthony York said in an email. “That’s also true for legal matters, including public records act requests. We trust agencies to use their discretion to notify the governor’s office as they see fit, depending on the issue.”

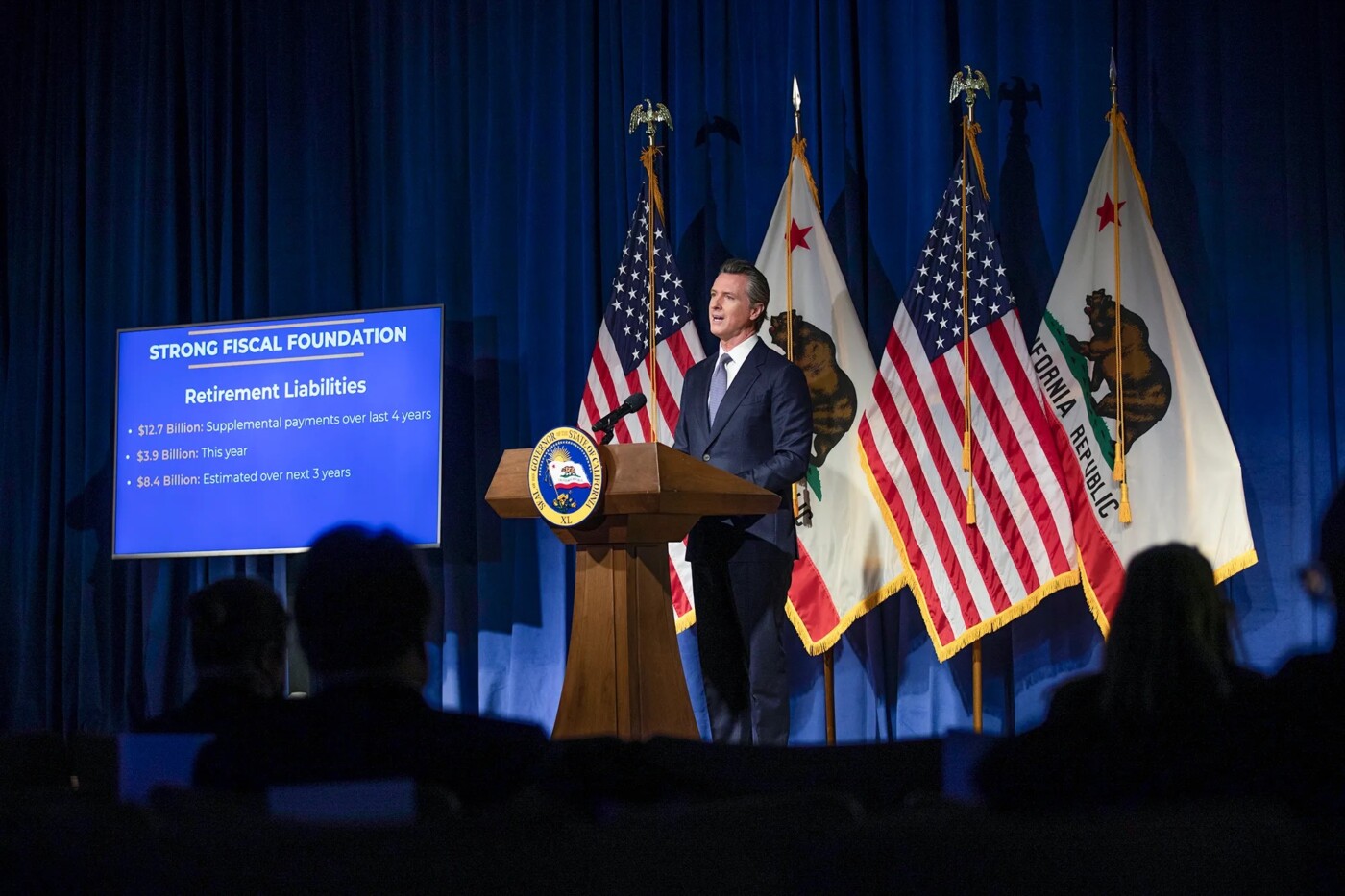

Newsom has faced criticisms of his own for his press strategy, including favoring the national media over California journalists for interviews and major announcements, which has contributed to speculation, repeatedly denied by the governor, that he is raising his profile to run for president. His office is also highly secretive about his schedule and travel compared to governors in other states, as The Sacramento Bee recently reported, and staff has on occasion physically blocked journalists from approaching Newsom to ask questions at public events, including the Capitol tree lighting ceremony in December and a march to his second inauguration in January.

Emails, not interviews

The obstacles and troubling behavior highlighted by the Capitol Correspondents Association of California are broader and more pervasive.

Many offices have moved nearly entirely toward written communications, directing a reporter who does reach someone by phone to instead send their questions by email. Some no longer list a media number on their websites at all, including the California Department of Public Health, which has often been the primary messenger for the Newsom administration’s pandemic response.

This approach favored by the state government restricts contact through official spokespeople; interview requests for policymakers and subject matter experts are frequently rejected, while agency employees are discouraged from speaking to the press without first getting permission.

During the pandemic, Julie Watts of television station CBS Sacramento spent two years investigating health and safety failures at a state-funded COVID-19 testing lab. She was never allowed to speak with Health and Human Services Secretary Mark Ghaly, who oversaw the state’s coronavirus response, or Department of Public Health officials about her findings, even after Newsom directed her questions to Ghaly.

Watts said she was forced to rely on written statements, which documents and reports often later revealed to be inaccurate or untrue. Without an opportunity to sit down with Ghaly, Watts said she could not fully push back on the state’s carefully constructed messages and get to the bottom of one of her central questions: Was California getting false information about the effectiveness of the lab, or covering up negligence?

“The answers they were sending us in writing were disingenuous,” Watts said, adding that it made her question whether the state had something to hide. “We were talking about complex, scientific issues. And it’s difficult to convey that to the public when it’s hundreds of back-and-forth emails.”

Anna Maria Barry-Jester covered public health in California for the nonprofit Kaiser Health News for nearly four years before moving last summer to investigative news outlet ProPublica. During that time, she said she was only ever granted one interview by the California Department of Public Health.

“The answer was nearly always ‘no,’” Barry-Jester said, whether she was seeking information about state programs, requesting data or trying to speak with an expert on staff. She said she encountered these limitations on stories about everything from rising syphilis rates to the coronavirus vaccine rollout to wastewater surveillance for COVID-19.

The pandemic illuminated the problems in stark terms, as Barry-Jester worked with public health departments in dozens of other states as well. From those agencies, she was able to get program descriptions, explanations for how they were tracking data, interviews with experts and insight into their biggest challenges confronting the coronavirus with limited resources.

“California’s was particularly obstructionist,” Barry-Jester said. “It was nearly impossible to get answers to basic questions.”

The written responses crafted by communications staff are often sent anonymously from a general email account, as though coming from the entire faceless bureaucracy rather than a particular spokesperson. For example, media inquiries fulfilled by the state Department of Justice, which is overseen by Attorney General Rob Bonta, are generally signed only “Press Office.”

The result is a slower, more complicated process for sharing public information. Follow-up and clarifying questions that would be quickly settled in an interview or phone call can be drawn out over days of correspondence. That’s a luxury of time that is not always available to reporters, especially in a breaking news situation. Sometimes those written responses blow through deadlines, coming after a story has been published or never at all.

Ariane Lange, an enterprise reporter for The Sacramento Bee, said she submitted a public records request to the Department of Health Care Services last summer for which she still has not received any documents.

Though she was initially told she would begin getting records in mid-September, related to the department’s relationship with an independent mediator that helped develop its doula benefit for Medi-Cal recipients, Lange said numerous attempts to get an explanation for the delay have been unsuccessful. Record requests are submitted through an online portal that does not allow for messaging, while her questions to the department’s media office about the situation have routinely been ignored.

After a public information officer told Lange that she didn’t even have a phone number where she could be reached, a frustrated Lange complained on Twitter last month that “email culture has gone too far.” She said she wants to get someone on the phone to find out if her request could be narrowed to speed up production.

“It feels like one of those things where we could work it out if we could just talk about it, but no one wants to talk to me at all,” Lange said. “It seems against the spirit of public service.”

Demanding better practices

In the guidelines it shared with reporters last month, the correspondents association recommended that media describe the rejection of an interview request in the story, alongside the written statement that an agency provides instead.

The association urged journalists not to provide questions in advance of an interview, other than a general description of the information they are seeking, writing: “Journalism ethics requires us to maintain our objectivity, and by giving these questions in advance you would be providing the office or agency an opportunity to rehearse for a basic function of their job and take control of the messaging.”

The guidelines also include a glossary of attribution terms and suggest pointing out in a story when government officials or spokespeople refuse to be identified, “especially in cases where a state agency is making an announcement or providing general information to a broad range of reporters.” One example the guidelines cite: A press briefing in October where the Newsom administration would not allow journalists to name the senior officials, including Ghaly, announcing the end date for California’s COVID-19 state of emergency.

Zavala, the association president, said the fragmented approaches of different media outlets have allowed state agencies to simply stick to whatever is easiest for their press teams. She said the reporting guidelines are intended to foster a unity among journalists to demand better practices. Alongside the document, the correspondents association also sent out a survey to collect more data from reporters about their biggest problems covering state government.

“We may be competitors, but it’s important for us to be on the same page,” Zavala said. “Journalists are the voices of communities, of people in this state, of voters, of taxpayers. We are the ones who have the opportunity to ask these questions on their behalf. That’s who we’re representing.”

Speed vs. accuracy

State communications officials said they aim to provide timely and accurate information to the media and the public, but those values are not always aligned.

Complex inquiries from reporters can require consulting multiple subject-matter experts for thorough answers and obtaining many layers of approval, sometimes in conjunction with other agencies.

Officials said they generally ask for questions in advance because it helps them determine who is best equipped to handle the inquiry. Providing interviews with agency staff can require a lot of preparation and coordinating schedules, so they often prefer to send written responses instead.

“We can’t just answer quickly to meet a deadline. It does nobody any favors if we provide information that is incorrect,” said Peter Melton, a public information officer with the Department of Industrial Relations.

The department declined a formal interview last summer for a CalMatters story on how few California workers are fully repaid even after winning wage theft claims, then nearly two weeks later, canceled an offer for a background conversation about its judgment enforcement unit to focus on a series of written questions the reporters had sent.

“If someone is asking highly-specialized questions that require someone highly specialized, they might not be available at that time,” Melton said. “If we put someone on the phone, and the questions are outside their scope, then it’s a wasted effort.”

Because many state employees are still primarily working from home, some large communications offices do everything by email so that their staff can collectively track and respond to the media inquiries they receive throughout the day.

“The quickest way to reach the team is through that inbox,” said Ali Bay, the director of communications for the California Department of Public Health, which removed the phone number for its press office from its contact page but maintains a general email address.

The department declined to make anyone available for a story CalMatters published last fall about how congenital syphilis rates soared in California over the past decade as public health funding fell. During a year spent working on the project, the reporter asked multiple times to speak to experts from the department’s sexually transmitted diseases control branch, but those requests were ignored and the department only answered questions for the story by email.

Bay said the department has been inundated with media inquiries since the pandemic, including more than 8,100 in 2020 alone. While the number has since dropped, to more than 1,800 last year, that still represents a nearly 70% increase over 2019. During that time, the department’s media team has grown to 10 positions, from seven, though it relied on staff from other agencies and contractors for additional help at the height of the pandemic.

“We do our best to accommodate interview requests, acknowledging that one person may not be equipped to answer all of the questions,” Bay said.

Spokespeople for offices that frequently provide unattributed responses said they prefer that the head of their agency serve as its voice.

“Where appropriate and depending on the context, our office is happy to accommodate requests for specific information to be attributable to an individual in the press office,” Bethany Lesser, the director of communications for the Department of Justice, said in a text message. “Our usual practice is for comments to come from the Attorney General or the department as a whole.”

These policies are generally not unlawful, noted Loy of the First Amendment Coalition, because public officials and state agencies are not legally obligated to speak to the press.

But many of them are nevertheless antithetical to the spirit of open government, he said, preventing journalists from obtaining the public information that they need to hold the government to account.

“Is the government there to serve the people or is the government there to be a spin machine?” Loy said. “It may seem inconvenient to the government, but at the end of the day, a government that is most accountable to the people is the best government.”