Mary Ann Pettway, manager of the Gee’s Bend Quilting Collective — a group whose distinctive, colorful coverlets have been featured in art institutions including San Francisco’s de Young Museum — wasn’t always enthralled with making quilts.

“I did not want to do it. My mother made me, and I’m glad she did,” Pettway told students at Oakland Technical High School during a presentation this week cosponsored by Oakland’s Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Center.

“Now God allows us to come here all the way from Alabama to share our growing up,” added Pettway, who made her first quilt, an “easy” nine-patch pieced pattern, when she was about 6 or 7.

“You’ve got to put forth the effort yourself. You can do anything you set your mind to. And you can be in a place where you don’t have a sewing machine,” continued Pettway.

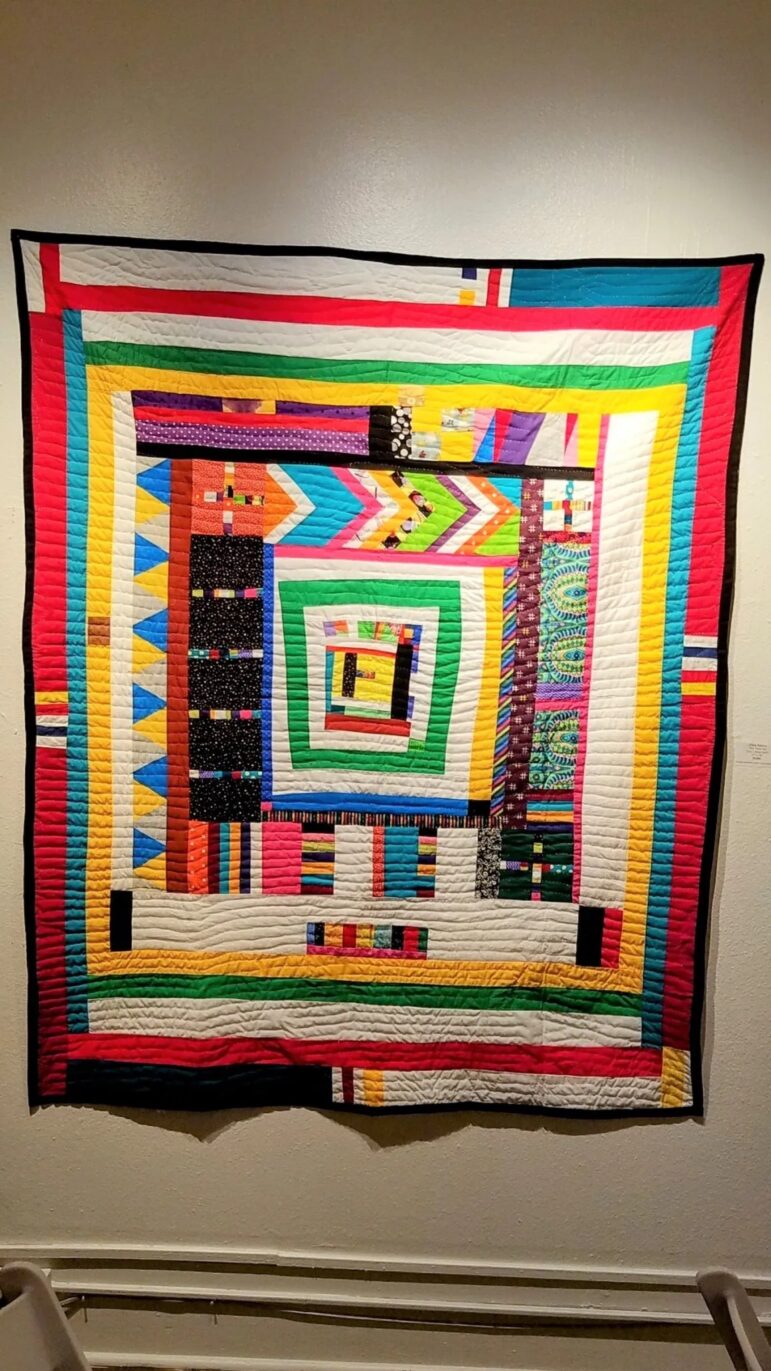

The two are in town on a tour to promote and sell the collective’s work, which is on display at Joyce Gordon Gallery in Oakland through April 1.

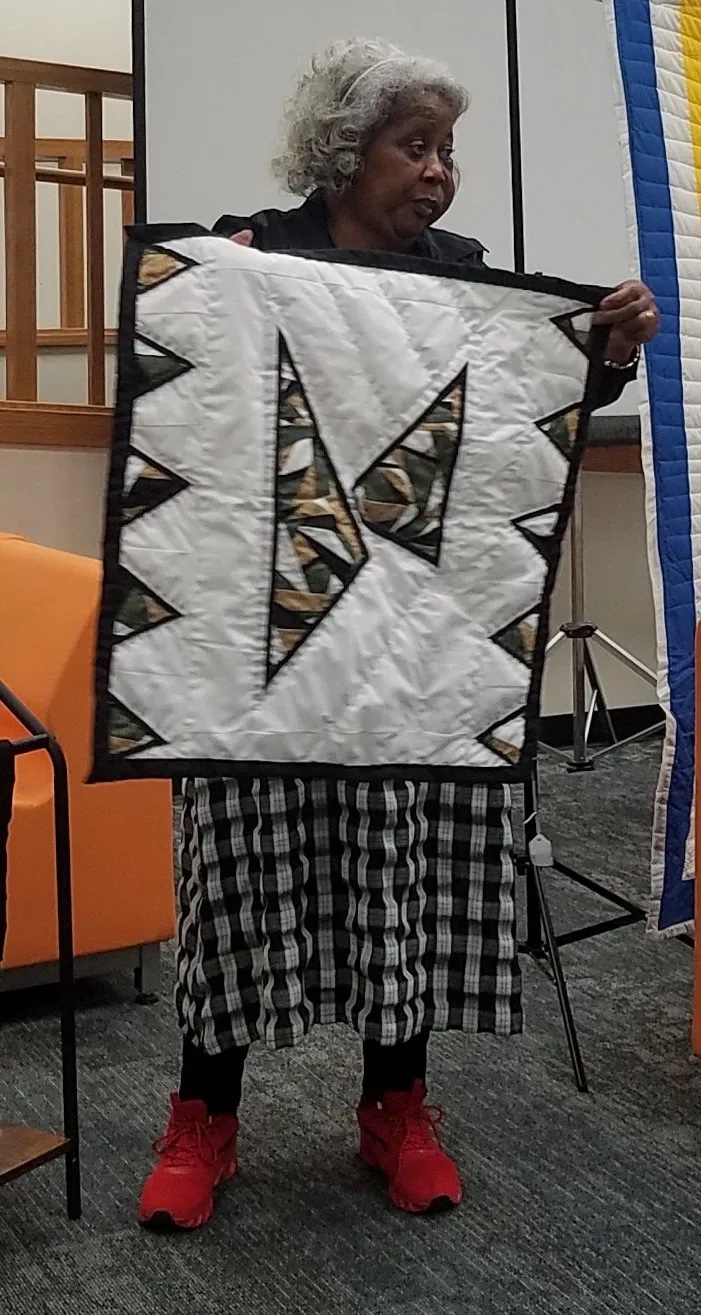

Pettway was joined by China Pettway (no relation), another collective member who explained that the generations-old quilt-making tradition in their small, rural remote town about 45 miles southwest of Selma (surrounded by the Alabama River and with a population primarily of slaves’ descendants) was born of the need to keep warm.

“We put quilts on doors, windows, beds. It was cold,” she said, mentioning that the heavy quilts were made from pieces of old, worn-out clothes.

“We didn’t have new material,” China said. At the time, quilts were viewed mostly as utilitarian objects.

“When I was in school, I didn’t get proper attention. I didn’t know about art. Then they discovered we were doing art,” China said, referring to “a crazy white man who paid good money” for a quilt made by Annie Mae Young.

The man was folk art collector and historian William Arnett, who organized a traveling exhibition of quilts made in Gee’s Bend that originated at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 2002; the show brought attention to the quilts, prompting the formation of the collective and organized moneymaking efforts. (Some of the large quilts in the gallery show are priced at more than $10,000.)

For Mary Ann and China — who take commissions, particularly for customers who are willing to wait — the effort has been successful.

“Find something you’re good at doing, and let someone pay you for it,” said Mary Ann, who, despite her reluctance as a child, enjoys quilting now: “Anytime you’re working on something and having fun, the time flies by.”

At the same time, she acknowledged, “Quilting is not something that’s fast. You just take your time.” If she can’t sleep, she gets up and starts working on a quilt. She’s partial to triangles in her designs.

Same goes for China, whose technique involves sewing together strips of different colored fabric, then using a roller cutter to create eye-catching patterns. She said that quilting makes her feel like she’s “somebody.” She added, “When I can’t get it together all night, I say to the quilt, ‘I’m making you. You ain’t making me.”

But Mary Ann’s grandson DeShuan Smith, who accompanied his elders on the trip and has a few works in the show, said he likes quilting because “it’s calming.”

The Gee’s Bend quilters also are good at another, more rousing endeavor: singing. China and Mary Ann ended their presentation by gorgeously harmonizing on an uplifting gospel number.

Its message nicely dovetailed Mary Ann’s mindset about how her quilts should look. She said, “It don’t have to be straight. It’s not going to be perfect.”

The Quilters of Gee’s Bend exhibition continues through April 1 at Joyce Gordon Gallery, 406 14th St., Oakland. Hours are 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesdays-Fridays and 1 to 4 p.m. Saturdays. Call (510) 465-8928.

Read more about the Gee Bend quilters in this essay by Alex Ronan.