State lawmakers are planning an oversight hearing that will look into how California handles toxic soil from old industrial, military and other cleanup sites — waste contaminated with things such as lead, petroleum hydrocarbons and the infamous insecticide DDT.

A CalMatters investigation last month revealed businesses and government agencies routinely dispose of contaminated soil at landfills in Arizona and Utah — states with weaker environmental regulation and oversight — as opposed to in California where the waste would need to go to specialized hazardous waste disposal facilities.

Two of the most heavily used landfills are near Native American reservations in Arizona, including one landfill with a spotty environmental record.

California state and local government agencies largely oversee or directly manage the cleanup projects disposing the waste out of state. California’s own hazardous waste watchdog — the Department of Toxic Substances Control — is one of the biggest out-of-state dumpers and has continued to take its toxic waste to Arizona despite the public revelations, according to information the department recently provided.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a national leader on environmental issues. His office failed to respond to requests for comment both before and after CalMatters’ initial report.

The as-yet unscheduled hearing had been planned to explore various hazardous waste issues, but the chair of the state Senate’s Environmental Quality Committee said it will now also probe the out-of-state dumping.

“It’s a real concern,” said Sen. Ben Allen, a Democrat from Redondo Beach.

“I think at a gut level, everybody feels as though every state should be handling its own toxic waste and not sending it across borders to other states and countries with less stringent environmental standards.”

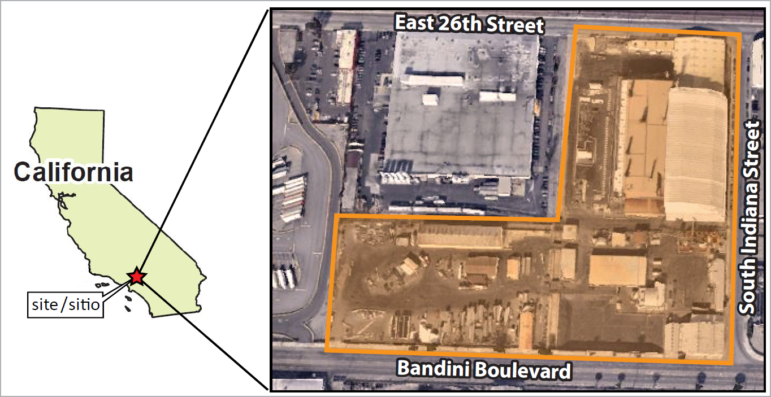

CalMatters’ reporting revealed that California businesses and government agencies have disposed of more than 660,000 tons of toxic soil in Arizona landfills since 2018 and nearly a million tons at a Utah landfill, according to data from the state’s hazardous waste tracking system. That includes more than 105,000 tons from the state’s cleanup of lead-contaminated soil in the neighborhoods around the old Exide battery recycling facility in Los Angeles County.

The out-of-state landfills are a cheaper option than California’s two hazardous waste disposal facilities, which are in Kings and Kern counties.

The Department of Toxic Substances Control took most of the Exide residential cleanup waste to the South Yuma County Landfill, which Arizona environmental regulators in 2021 labeled as posing an “imminent and substantial threat” after an inspection noted windblown litter, large amounts of “disease vectors” (flies and birds), and groundwater with elevated levels of chromium – a metal that can harm people and the environment.

The landfill did make fixes to resolve those and other violations, according to Arizona regulators.

Exide waste has continued to go to that state. The Department of Toxic Substances Control shipped 52 loads of hazardous waste from the Exide residential cleanup to the Yuma landfill from Jan. 25 to Feb. 10, according to figures the department provided.

In Arizona, one lawmaker told CalMatters that she wasn’t aware California was dumping so much hazardous waste in her state’s landfills and called it “very concerning.”

“Arizona is not a dumping ground and hauling California’s hazardous waste so close to Arizona’s agricultural hub and the Colorado River is asking for trouble no matter how many precautions they take,” said Arizona state Rep. Mariana Sandoval, a Democrat whose district includes areas around the South Yuma County Landfill. “I would hope that our new governor will take a close look at this…and encourage California to find landfills in their own state for their own waste.”

New plan coming for California toxic waste

As to whether Californians can expect any major policy change, officials largely pointed to a 2021 law requiring the state to craft a new hazardous waste management plan. As part of the process, the Department of Toxic Substances Control is scheduled to release a report in March looking at how much hazardous waste the state is generating and how it’s being handled.

“The (Hazardous Waste Management) Plan will propose strategies for reducing hazardous waste generation, managing more waste in state, and addressing issues of concern, such as hazardous waste impacts to disadvantaged communities,” according to a statement from the department.

A proposed plan isn’t due until spring 2025.

Asked how the state can justify continuing to dump hazardous waste in out-of-state landfills next to Native American reservations, California’s secretary for environmental protection, Yana Garcia, declined an interview request but provided a written statement.

“The hazardous waste challenges we face across the country are decades in the making. While we know these issues won’t be resolved overnight, California is fully committed to addressing this urgently, and we are prioritizing investing in the search for solutions to do so,” according to her statement.

She said the bill that led to the hazardous waste planning process as well as more stable funding for the department “improved our ability to address this and other toxic waste challenges. Enhancing DTSC’s regulatory oversight and requiring the research and public engagement necessary to come to consensus on solutions moves us in the right direction, but our path to achieve on-the-ground improvements will require true partnership with a multitude of stakeholders and a fundamental shift in how we produce, treat, and handle hazardous waste, across the board.”

Hazardous waste landfills in San Joaquin Valley

Regulators, environmental advocates and lawmakers said the issue is complicated and any solution is likely to be controversial.

California is limited in its ability to regulate interstate commerce. State regulators said there’s not much they can do to stop private entities from taking waste across the border.

And California has only two hazardous waste landfills, both of them in the San Joaquin Valley: the Kettleman Hills Facility in Kings County and the Buttonwillow landfill facility in Kern County.

On paper, the sites appear to have enough space to take contaminated soil. Last year, Jennifer Andrews, a spokeswoman for WM (formerly known as Waste Management Inc.), which operates the Kettleman Hills facility, told CalMatters the site “has enough capacity to meet the State of California’s hazardous waste disposal needs.”

“We also have plenty of space to meet the needs of (Department of Toxic Substances Control) waste for years to come, providing the agency permits new disposal units at our site.”

But the two landfills have been controversial. Both were the subject of numerous regulatory violations over the years and advocates have long protested about the sites, which are near communities of color. In 2014 the Department of Toxic Substances Control approved an expansion at Kettleman Hills, prompting environmental justice and community groups to file a civil rights complaint, records show.

Bradley Angel is executive director of Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, one of the groups that filed the complaint, which ultimately led to a settlement agreement including provisions for more health assessment and environmental monitoring, state records show.

“They need some other alternatives and the reality is I don’t see them building another hazardous waste landfill,” Angel said.

He said there’s “not the political appetite.”

Indeed, the Department of Toxic Substances Control appeared to acknowledge as much in a 2017 report that looked at ways to reduce hazardous waste including treating more contaminated soil on site as opposed to excavating it. The report cited a “difficulty in gaining consensus in the siting of new facilities” as leading to a focus on strategies to reduce the amount of hazardous waste generated.

In other words, if you can’t build more sites to take hazardous waste because nobody wants it in their backyard, then you better figure out a way to make less of it.

Cleaning up hazardous soil

California’s efforts to address a long history of environmental harm at old industrial and military installations produces hundreds of thousands of tons of toxic soil each year.

The Department of Toxic Substances Control “is trying to remediate contamination that was created over decades by unscrupulous private sector actors. Now, does that mean they ought to be dumping in Arizona?” Sen. Allen asked.

The senator said his committee will hold an oversight hearing on the Department of Toxic Substances Control some time this year. Other topics will likely include recent reporting from the Los Angeles Times suggesting the state isn’t ensuring properties around the Exide facility are properly cleaned of lead-contaminated soil.

“There’s not an easy answer here. But that doesn’t mean that we accept the status quo,” Allen said.

Other states could, of course, also take action. Oregon in the late 1980s adopted a rule that effectively bars California from dumping hazardous waste in that state’s regular landfills. Nevada has a similar rule. (California disposed of a large amount of contaminated soil at a Nevada facility in recent years, shipping records show. But that site is designed and permitted to handle hazardous waste.)

The lawmaker whose district includes an area around the South Yuma landfill said Arizona legislation to restrict California’s dumping is possible.

“Nobody wants that in their backyard,” Sandoval said. “Obviously California doesn’t want it in their backyard. That’s why they’re bringing it over to us.”

Utah legislators CalMatters reached out to didn’t respond to requests for comment. Regulators in that state recently signified their intent to deny a permit for a landfill on the banks of the Great Salt Lake that CalMatters reported was planning to take California’s contaminated soil. CalMatters reported in January that the company behind the project filed an economic analysis with its state regulators calling the toxic soil a “unique market opportunity created by California law.”

The proposed permit denial indicates there is already enough landfill capacity to handle Utah’s waste needs.