For northern California housing politics, judgment day has come.

Cities across the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area had until Wednesday to show state regulators how they plan to approve a sufficient quantity of housing over the next decade.

Some submitted their plans on time. Most did not. Some made an earnest effort to comply. Others not so much. Some will have their plans accepted. Others have already had theirs rejected. Suburbanites viscerally opposed to new construction and density in their neighborhoods are incensed. Pro-development activists are celebrating a “Zoning Holiday.”

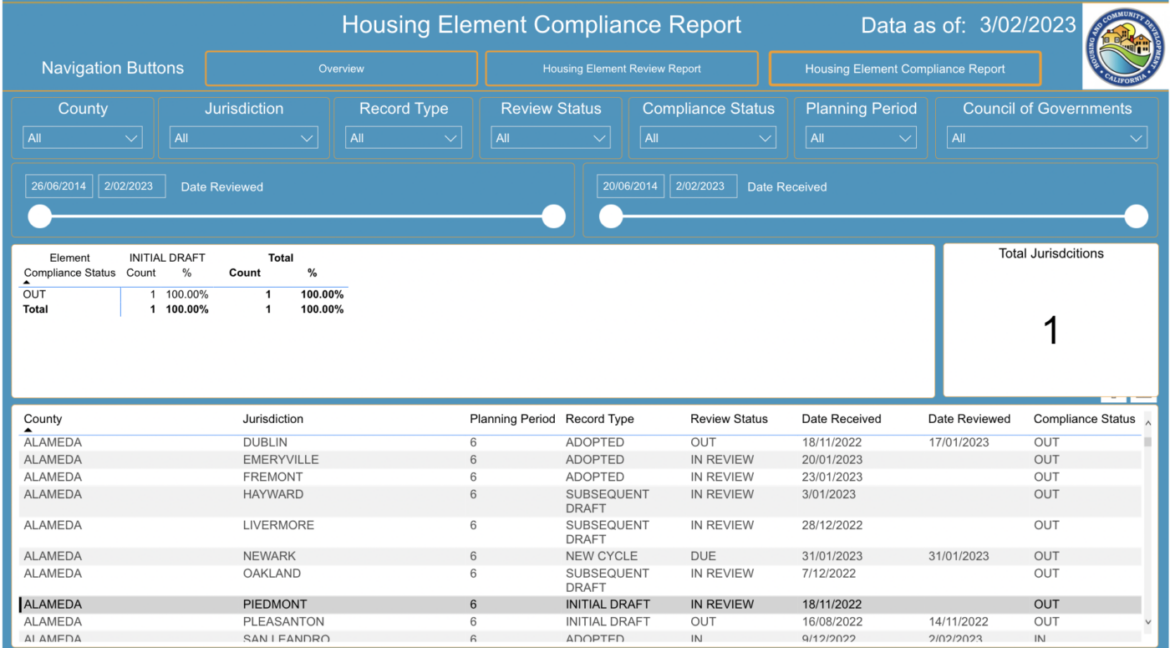

As of Thursday afternoon, of the 109 cities and counties in the region, 66 have either had their plans rejected, or failed to submit one at all. Two have had their plans approved and finalized: San Francisco, which approved a plan for 82,000 additional units, and the city of Alameda, which agreed to make room for another 5,000 homes and apartments. Emeryville and Redwood City have both gotten tentative thumbs- ups, too.

While Gov. Gavin Newsom celebrated the San Francisco approval, 82,000 units in eight years is a far cry from his statewide goal of 2.5 million, which itself is a big cut from the 3.5 million he campaigned on in 2018.

With housing scofflaws abounding, the question remains: What’s the state going to do about it?

First, a brief primer on how we got here:

- Since the late 1960s, the state has been telling local governments how much housing they need to plan for to accommodate a growing population.

- Throughout most of the law’s history, the state hasn’t done much to actually ensure that locals comply.

- In recent years, a series of laws authored mostly by Bay Area Democrats in the Legislature ramped up the state’s housing goals and gave the law teeth.

- Also on the books: The “builder’s remedy” that forces cities and counties that are out of compliance with state planning rules to approve any housing anywhere, as long as 20% of its units are set aside for low-income renters and buyers.

Advocates on both sides of the issue have been alternately clamoring for, and dreading, a “builder’s remedy” bonanza. But housing experts note that we’re in uncharted waters.

- UC Davis law professor Chris Elmendorf: The old law is “so poorly drafted and confusing that developers of ordinary prudence haven’t been willing to chance it.”

- Jordan Grimes with the Greenbelt Alliance: “Most advocates expect there to be litigation around the issue. So much of this is untested.”

Southern California may provide some glimpse of the Bay Area’s future. The state has been slow-rolling its housing plan deadlines, region by region, and much of Southern California fell out of compliance in mid-October. The legal battles are on: Huntington Beach has vowed to “unleash” its city attorney against the state’s mandates and housing groups are suing Beverly Hills to see whether the builder’s remedy applies there.

Top of mind: In a statewide survey this week from the Public Policy Institute of California, 60% of respondents said they were “very concerned” that the cost of housing will prevent younger members of their family from buying a home in their part of the state.

That’s compared to 4% who reported being not at all concerned. Lucky them.

But there’s some progress: A dozen community colleges have been awarded $500 million (with hundreds of millions more on the way) to build new dorms and expand existing ones. Andrea Madison and Katherine Bent with CalMatters’ College Journalism Network reported on two new projects that offer different possible versions of the future for California’s student housing.

You can

City says it expects Housing Element to be adopted in late February or March