On a recent night, by the Miramar Reservoir in San Diego County, a man named Erwin sat at a picnic table scrolling through dozens of texts from his wife. He read aloud her warnings about police patrolling a road near their home.

“‘There’s a lot of cops out tonight,’” he read. “Cops everywhere.’ ‘Be careful; lots of cops.’ ‘Too many cops.’

“Every time I want to get a burger or juice or anything like that and I leave the house, she will text me ‘There’s a lot of cops. Be careful,’” Erwin explained. “It’s a reality that we live in. We adapt our life and our every day to it.”

Erwin, who asked not to use his last name for fear of deportation, is a 27-year old business manager, husband and father of a 6-month-old baby girl. He’s also a Congolese immigrant whose visa expired. His wife, a U.S. citizen, fears what would happen if police stop him.

Although California is a sanctuary state — with protections for immigrants who lack documentation authorizing them to be in the United States — there are loopholes and law enforcement sometimes works with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Beyond that, Erwin worries a traffic stop might escalate.

“Believe me, in my country, I would never have to worry about getting pulled over and being scared that they’re going to shoot me,” he said.

Erwin wants to swap his foreign driver’s license for a California one.

“Before I didn’t have a family, so I could risk it,” he said, “but now I have my family and I drive my kid everywhere we go. So I decided to get right and get the driver’s license, so it’s less of an issue if I get pulled over.”

A license to drive

Erwin has made multiple attempts to obtain an AB 60 driver’s license. It’s a special license that lets undocumented California residents legally drive, but with federal limitations.

Proponents say the special license was a boon to immigrants and the state’s economy. But critics, and even some immigrant advocates, say it has drawbacks and risks, since law enforcement and immigration officials can access it. Nevertheless the state is expanding its flexibility, giving IDs to more undocumented residents.

California lawmakers first passed AB 60, called the Safe and Responsible Drivers Act, in 2013, as part of a broad effort to adopt more inclusive policies toward immigrants, to decriminalize their daily lives and maximize their contributions to the economy, experts said.

Since the law took effect in 2015, more than a million undocumented immigrants, out of an estimated 2 million, have received licenses, and more than 700,000 have renewed them.

Besides California, 18 other states have followed suit.

“With AB 60, what we did was recognize the needs of many hard-working immigrants living here and contributing so much to our great state,” said Luis Alejo, the former Assembly member from Watsonville who authored the bill. Now he is a county supervisor for Monterey County.

Undocumented immigrants in California contribute $3.1 billion a year in state and local taxes; nationally they contribute $11.7 billion in taxes, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a Washington D.C. research entity.

New legislation signed in September will make other California ID’s available in January to undocumented immigrants who don’t drive or who can’t take the driver’s test. Backers of that measure say residents most likely to benefit are the elderly and people with disabilities.

“IDs are needed for so many aspects of everyday life, from accessing critical health benefits, to renting an apartment,” said Shiu-Ming Cheer, deputy director of programs and campaigns at the California Immigrant Policy Center, a sponsor of the law.

Experts say more flexible ID laws may do more than help people on an individual level. Eric Figueroa, a senior manager at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said licenses enable undocumented immigrants to look for better jobs and gain better protections from employers trying to steal or withhold wages.

“It helps build the economy broadly — by unlocking people’s potential — and it helps the workers by giving them more options,” he said.

Erwin uses family connections to remotely renew his Congo license — a privilege he noted not everyone has. Being able to drive allowed his family to move to a better neighborhood and him to find better employment in a suburb about 25 miles away, he said.

No one has studied how many people have garnered better jobs as a result of the special licenses. Alejo said many of his constituents describe “profound economic impacts,” but he agrees more research is needed.

Some opponents of the licenses say their economic benefits are likely negligible. Instead it is encouraging illegal migration to California, they say, which further strains the state’s budget to provide education and other services.

More than that, it makes undocumented residents too comfortable, critics argued.

Before the special licenses, immigrants said they feared routine traffic stops and drunk-driving checkpoints, where their vehicles could be impounded for not having a driver’s license. Many also could face deportation proceedings after being contacted by police.

“Community members used to share that they always used to have to buy beat-up cars because they always knew it would get impounded,” said Erin Tsurumoto Grassi, policy director at Alliance San Diego, a community organization focused on equity issues.

“Folks were always losing their vehicles because they didn’t have a license. They didn’t have the ability to have a license,” she said.

Accident trends

Some opponents of the special license law claimed it would make roadways less safe, because some immigrant drivers wouldn’t be able to read traffic signs in English.

But a 2017 study by the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford University showed those safety concerns were speculative. The rate of total accidents, including fatal accidents, did not rise and the rate of hit-and-run accidents declined, which likely improved traffic safety and reduced overall costs for California drivers, researchers said.

The study, which documented a 10% decline in hit-and-run accidents, ran in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in April 2017.

“Coming to this as scientists, we were immediately shocked by the absence of facts in this debate,” said Jens Hainmueller, a Stanford political science professor and co-director of the lab. “Nobody was drawing on any evidence; it was more characterized by ideology.”

Other research by Hans Lueders, a postdoctoral research associate for the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice at Princeton University, found AB 60 did not improve insurance premiums nor increase the share of uninsured drivers.

Are license holders safe?

Questions persist about whether the special licenses make recipients easier targets for immigration enforcement.

Some immigrant advocates initially opposed the new licenses because they looked different from other driver’s licenses. On the front of the cards’ upper right side is “Federal Limits Apply” instead of the iconic gold bear of California. On the back the cards say: “This card is not acceptable for official federal purposes.”

Alejo said legislators had intended to protect people from immigration enforcement, so they wrote certain protective measures into the original AB 60 bill. They added language prohibiting state and local government agencies from using the special license to discriminate against license holders or for immigration enforcement.

Yet some advocates point to reports of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement accessing the databases of state and local law enforcement agencies and of state departments of motor vehicles.

In December 2018, the ACLU of Northern California and the National Immigration Law Center published a report detailing multiple ways federal immigration agencies get access to motor vehicle records. After that, the California Attorney General’s Office implemented new protocols to protect immigrants’ DMV information from ICE and other agencies.

A chilling effect

Dave Maass, director of investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said there is always going to be a risk someone will misuse data on undocumented people.

“I wouldn’t say that people should feel 100% safe,” he said.” I would just say that the risk has been lessened quite a bit … but that does not mean the risk has totally gone away.”

In recent years there has been a large drop-off in the number of immigrants applying for AB 60 licenses. According to the Department of Motor Vehicles, 396,859 immigrants applied for the licenses in fiscal 2014-15, but only 68,426 applied in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2022.

Advocates said that may be because most people who wanted a license applied for it already, or because education and outreach about the law have lessened over the years.

Cheer said news of ICE accessing California databases could have a chilling effect on immigrants’ willingness to interact with government.

“It does create more of a trust deficit with government agencies whenever there is a story about ICE having access to California databases or information in California databases,” she said.

Being seen

On the other hand, there’s an added benefit to the new licenses, Cheer said: immigrants now have a feeling of being included and acknowledged as residents of California.

“I feel like that’s a very important psychological piece, in the sense of ‘This is who I am. I have an ID to show you who I am,’” she said.

Erwin said he carefully weighed the possibility that he would be effectively giving ICE his home address against wanting to have the proper paperwork, so there would be no excuse for a police officer to escalate a traffic stop with him. He decided one risk was worth reducing the risk of the other.

For some immigrants, the passage of the license law didn’t come soon enough.

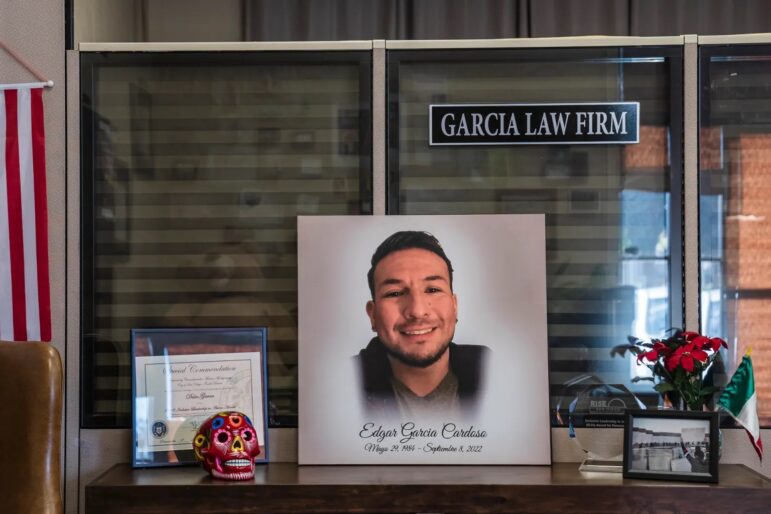

Dulce Garcia, an attorney and advocate for immigrants, recently described at a San Diego public forum on immigration enforcement what happened when police stopped her brother who was undocumented.

Police cited Edgar Saul Garcia Cardoso for driving without a license and when he appeared in a courthouse in January 2020 to face the consequences, ICE detained and deported him, within hours, to Tijuana, she said.

There he was kidnapped, held for ransom and tortured for eight months, Garcia said.

In May 2021, he returned to the United States and received asylum protections. But he never recovered from the trauma, Garcia said. He died of unknown causes in September 2022.

“I wish there was a way you could see through my eyes the harm you have caused by colluding with ICE,” Garcia told law enforcement officials at the forum. “Edgar was loved, and his life mattered.”