Funding for schools and community colleges will fall next year for the first time in a decade, under the first pass at the 2023-24 state budget, which Gov. Gavin Newsom released Tuesday. Both the University of California and the California State University would receive 5% base increases. (Go here for more details on higher education funding.)

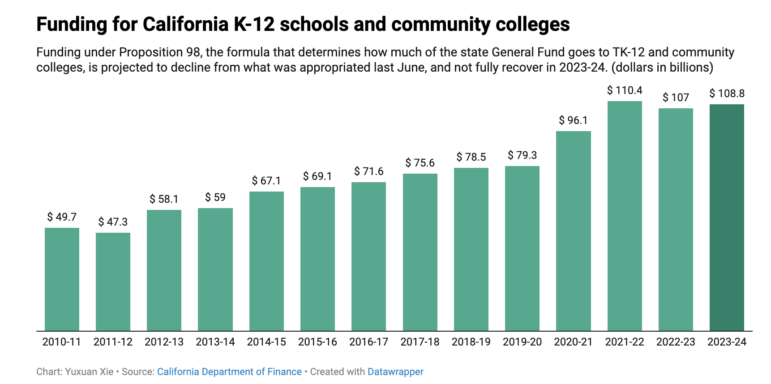

Newsom projected a drop of $1.5 billion below the $110.4 billion the Legislature approved last June for Proposition 98, the formula that apportions how much of the state’s general fund goes to TK-12 and community colleges.

He said that the state would meet the statutory requirement to pay a projected 8.1% cost of living adjustment, the highest rate in four decades. School organizations have reiterated that funding COLA would be their top budget priority this year.

“That’s a number I never expected to see…” Newsom said. “It’s an expression of our commitment to equity.”

The COLA increase would apply to general funding through the local control funding formula as well as special education and other ongoing programs.

At the same time, he said he would continue the big initiatives he funded during the past two years, including $4 billion for community schools, $12.5 billion for learning recovery from Covid and $4.7 billion for mental health needs. “We’re going to continue these commitments. We’re not backing off,” he said during a lengthy budget presentation.

Schools would fare relatively well compared with other areas in the budget plan, as the state grapples with a projected $22 billion shortfall in the general fund. While Newsom is proposing funding delays and cuts to climate change, transportation, housing and workforce development programs, he mostly committed to keeping cuts away from schools.

Newsom’s forecast does not assume there will be a recession, and much could change between now and May, when the governor issues a revised budget based on updated revenue forecasts, followed by negotiations with the Legislature.

The drop in Proposition 98 funding — several billion less than the Legislative Analyst Office projected in November — follows 10 years of funding increases. Between 2019-20 and 2021-22, the minimum guarantee alone grew $31.3 billion to $110.3 billion, or 39.5%. It was the biggest increase in any two-year period since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988, according to the LAO. The drop in 2023-24, if it holds, would erode only a small portion of this gain.

Despite less money, TK-12 per-student funding under Proposition 98 would actually rise slightly to a record $17,519 in 2023-24. That’s because of declining enrollment. Under Proposition 98, schools and community colleges will continue to receive 39% of the general fund revenues, dividing it among a shrinking number of students. Total per-student funding, with funding from the federal government and other sources, will be $23,723 next year, according to the Department of Finance.

Newsom is projecting that Proposition 98 revenue for 2022-23 will fall $3.5 billion below what the Legislature approved last June. Rather than cut ongoing funding or backfill with money from the $8.3 billion education rainy day fund, he would make up the difference by delaying money for kindergarten facilities, cutting $1.2 billion from one-time discretionary funding for arts and instructional materials and applying other unused one-time funding.

Newsom is not proposing new big-dollar programs. However, he would broaden the local control funding formula by $300 million through what he is calling an equity multiplier, a new school-based funding concept that is an effort to address a commitment he made last year to Assemblywoman Akilah Weber, D-La Mesa. It would provide additional funding to the highest-poverty schools to address underlying issues behind the lowest-performing students — as identified by the California School Dashboard.

“This is an important investment that would double down on improving opportunities and closing gaps at our state’s lowest-income schools. And we’re particularly pleased to see the funds focus on improving teacher quality at the neediest school sites,” said John Affeldt, managing attorney and director of education equity at Public Advocates.

But Weber’s plan, in a bill she withdrew last year, would have provided extra funding for the lowest-performing student group not already receiving extra funding under the formula. Black students statewide persistently have been that group. Fewer than 1 in 6 Black students met standards in math, compared with one-third of all students, in the latest Smarter Balanced results.

One issue of disagreement is whether her bill would violate Proposition 209, which bans preferential treatment on the basis of race and ethnicity in public education. In a statement on Tuesday, Weber did not endorse Newsom’s proposal, but she called it “a step in the right direction” and said she looked forward to continued discussions.

Newsom is also proposing:

- $250 million more to districts with the lowest income elementary schools to hire and train literacy coaches. The number of schools with literacy coaches will double.

- An additional $1.5 billion to continue other programs designed to increase the number of qualified teachers in classrooms including the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, which pays teachers with needed credentials up to $20,000 a year to work in schools that have a high number of foster youth, English learners and students from low-income families, and the Classified School Employee program, which helps classified staff earn a bachelor’s degree and teaching credential. “These investments have begun to increase the number of fully prepared teachers graduating from California teacher education programs and entering the state educator workforce, and to reduce the number of teachers who are hired on substandard credentials,” according to the budget summary.

- $100 million to enable high school seniors to visit museums, attend theater performances or enjoy other arts enrichment activities. The funding amounts to about $200 per student.

Susan Markarian, president of the California School Boards Association, praised Newsom’s previous commitments to extending the school day and funding learning recovery while providing the full cost-of-living adjustment. “Combined with an additional investment to implement transitional kindergarten, this budget contains important tools school districts and county offices of education can use to fund academic interventions, supplemental services and mental health supports,” she said in a statement.

But she also called for “more action to address the staffing shortage and provide pension relief at a time when 25 cents of every dollar received by local schools goes toward pension obligations.” She also requested “more robust support for schools to combat cyberattacks that put student and staff privacy at risk and compromise school operations.”

Consistent with previous years, the governor’s budget includes reforms for Special Education Local Plan Areas — the organizations that oversee services for disabled students in California public schools. The budget extends the moratorium on new SELPAs, increases transparency for SELPA budgets and governing plans, and limits the amount of money SELPAs can spend on services not directly related to children, such as financial support and monitoring.

But administrators will have to wait until May’s budget revision for more details on what these changes will actually mean, said Anjanette Pelletier, director of management consulting services for School Services of California.

“We definitely have to wait to see more detailed language,” she said. “But I feel it continues the path we’ve been on.”

Aaron Benton, Butte County SELPA director and communication chair of the SELPA Administrators Association, said SELPAs need more support from the state, not less.

“We applaud the efforts of the Administration and Legislature” to increase base funding, he said, “but we believe the surest way to address the achievement gap and improve outcomes for students with disabilities is for the state to strengthen SELPA structures.”

Early education

Newsom reaffirmed his commitment to offering transitional kindergarten to all 4-year-olds by 2025, eventually at an ongoing cost of $3 billion per year. Last year, more than $600 million was funded for the first year of eligibility, where all children turning 5 years old between Sept. 2 and Feb. 2 were eligible.

Newsom is proposing $690 million to implement the second year, in which 46,000 more children will be eligible when the cutoff date moves from Feb. 2 to April 2. In addition, $165 million is proposed to support adding one certificated or classified staff person in every TK classroom.

The proposed budget delays adding more child care slots toward the goal of an additional 200,000. Funding for 20,000 new slots will be funded in 2024-2025, instead. Thousands of the previous slots have not yet been filled, which providers attribute to funding too low to hire more staff.

Child Care Providers United, the union that has worked on legislation and reimbursement negotiations, said they were disappointed to see the delay “at a time when families are still in critical need of quality, affordable child care for all ages, beyond just TK. …”

“We also recognize that without increases in provider pay and investments in provider safety nets, including retirement investments, new talent won’t enter the workforce,” their statement continued. “Delays in expansion only serve to hurt California’s working families.”

The budget also includes an additional $116 million to continue a multiyear plan to ensure preschools enroll more dual-language learners and children with disabilities. In 2023-24, state preschools, which serve low-income families, are required to make students with disabilities at least 7.5% of their enrollment, and to also provide more support for dual-language learners.

EdSource reporters Ali Tadayon, Carolyn Jones, Diana Lambert and Ashleigh Panoo contributed to this report.

Correction: The original version incorrectly stated that the proposed budget includes an additional $1.5 billion to develop the teacher workforce through a block grant program. That money was appropriated in an earlier budget.