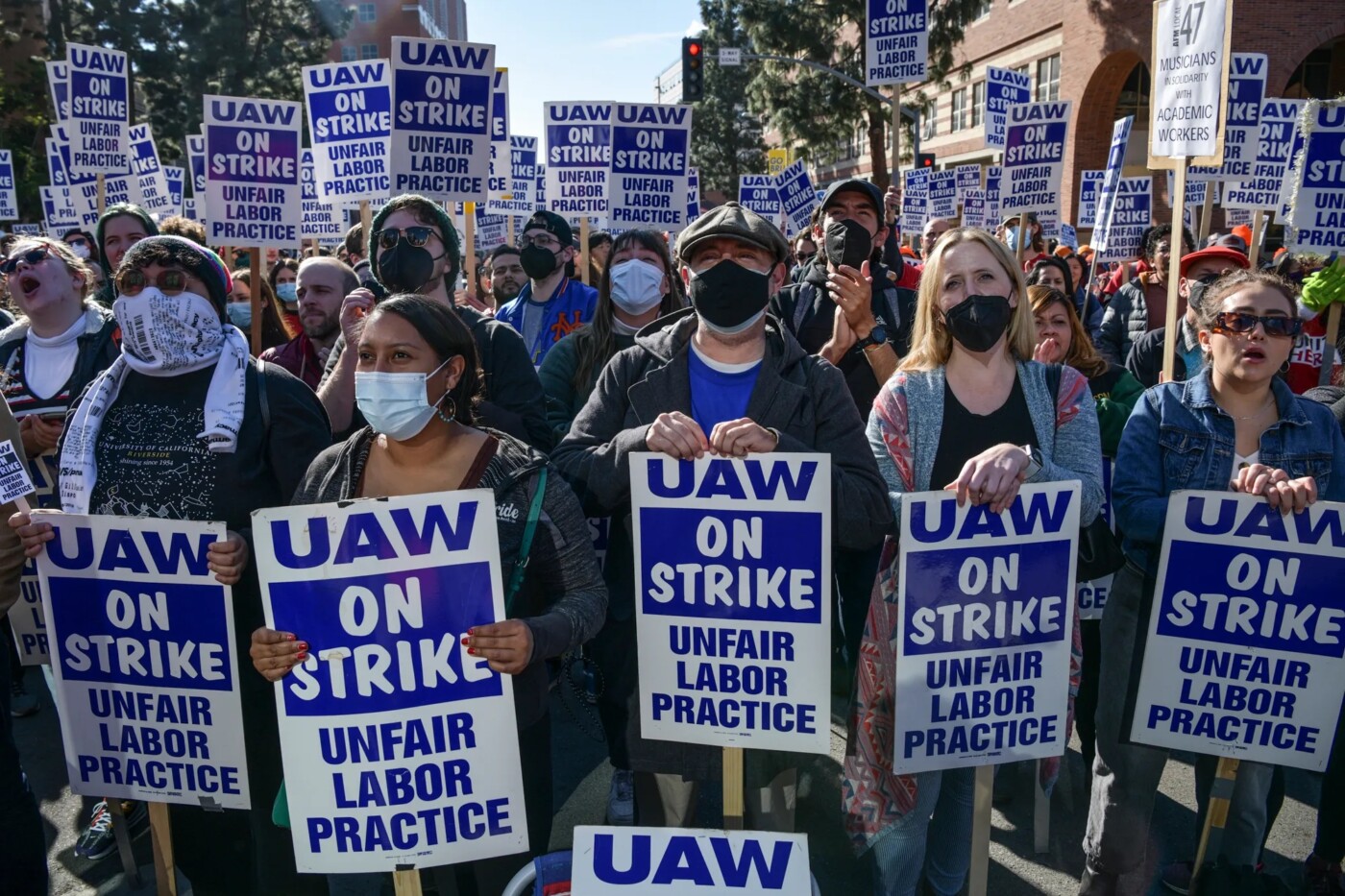

As a labor standoff drags into its second month at the University of California, the graduate student workers on strike are bringing their fury — and hopes for higher wages and benefits — directly to UC leadership through civil disobedience and other tactics that go beyond standard picketing.

Across several episodes in recent weeks, dozens of striking academic workers have ramped up their activism, putting themselves in positions that they know lead to handcuffs and arrest.

“There are lots of members who are very frustrated with the process so far … and they are ready to escalate, and they have been escalating by engaging in civil disobedience,” said Rafael Jaime, a doctoral candidate in English at UCLA who is president of United Auto Workers 2865, the union representing 19,000 mostly graduate students who work as teaching assistants, tutors and instructors.

Several academic workers who were arrested in the Los Angeles area agreed, telling CalMatters that the slow pace of negotiations compelled them to ratchet up their protests, in particular targeting members of the UC Regents, the governing body that oversees the university system. The regents have huge sway over the decision-making of the UC Office of the President, which is handling the negotiations with the remaining 36,000 tutors, teachers assistants and graduate researchers on strike.

On Tuesday, 14 academic workers were arrested after two acts of protests forced the regents to temporarily halt their planned meeting for several hours.

The first wave of arrests occurred just before noon, after all but four of the roughly two dozen protesters who snuck into the well-guarded conference space filed out of the building and disrupted a closed meeting of the regents. The remaining four refused police orders to disperse.

The second set of arrests unfolded during the public comment period in the afternoon. After a graduate worker pleaded with the regents to use their influence to offer the striking workers a better contract, 10 other graduate student workers crossed into the reserved area where regents sit during meetings and sat on the floor, shouting “if we don’t get it, shut it down.”

For roughly half an hour they chanted, clapped and sang to a nearly empty chamber as almost all the regents peeled off into a private room just moments after the unrest began. UC police eventually ordered the student workers to disperse. None did and all 10 were handcuffed as they sang “solidarity forever, for the union makes us strong” — the last two to be arrested carrying the solemn tune by themselves.

At least one regent doesn’t think the strategy is effective.

“The best way to get the deal is to have their negotiators negotiate with our negotiators,” said Regent Jay Sures in a brief interview during the demonstration. Asked whether shutting down the regents meeting compels him to encourage the UC to come to a deal quicker, Sures said “no.”

“It’s clear that with all our striking and protesting and picketing, the university is just not listening to our demands, and they’re not responding,” said Omer Sohail, a graduate student researcher who was one of the four arrested in the morning disruption on charges of trespassing and unlawful assembly.

“We do this because we feel like we’re powerless … and all we have is our bodies and our ability to disrupt a public meeting.”

Juan Pablo Gatica, a graduate student researcher who was one of 10 arrested in the afternoon, said he viewed his civil disobedience as a way to escalate the strike effort after traditional picketing didn’t lead the UC to propose a salary offer he likes.

The acts coincided with a large rally steps from where the regents were meeting on the UCLA campus. Tom Morello, best known as guitarist for the politically left hard-rock group Rage Against the Machine, performed union protest songs.

“Whenever there’s a strike, I’ve got a guitar, I’m willing to play it,” Morello told CalMatters after his set. “My whole career has been about finding ways to use a guitar as a battering ram for social justice.”

Last week, scores of striking workers rallied outside the Los Angeles home of Sures, who is also vice chairman of United Talent Agency — among the largest entertainment talent agencies in the country. Also in Los Angeles, another group of several dozen graduate student workers flooded the hallway and office of The David Geffen Company, directed by another UC regent, Richard Sherman, last Wednesday. As a result, 10 graduate workers were arrested, cited and given a court date.

The actions are an escalation “showing our power and willingness to fight for a fair contract,” said Riley Marshall, 24, a striking graduate academic worker who has helped to organize some of the civil disobedience in Los Angeles and was among the 10 union members arrested last week. “We aren’t just sticking to our departments; this is going after the totality of the UC.”

Across California, striking graduate workers have disrupted university operations through rallies, sit-ins and protests. Last Monday 17 graduate workers were arrested for trespassing during a rally at the UC office of the President in Sacramento. The week before, strikers filled the hallway outside the office of UC Berkeley’s chancellor and then marched on her home. Strikers also rallied outside President Michael Drake’s UC residence in Berkeley, a mansion that the UC purchased last December for $6.5 million. Striking workers have also occupied campus office buildings and events spaces.

Those efforts are an attempt by the striking workers to slow operations at the university system, a strategy the academic workers believe will get them closer to the labor contracts they want.

The strike, thought to be the largest-ever display of university workers withholding their labor in the U.S., has already resulted in missed finals and canceled classes for many of the UC’s more than 200,000 undergraduates.

Graduate student workers provide much of the teaching and research at the university system. Groups representing professors vowed to support their strike and opt out of performing their grading and research labor.

The two remaining unions representing 36,000 graduate student workers are pushing for minimum salaries of $43,000 a year, down from their original demand of $54,000. Currently, the graduate student workers earn an average of $24,000, a salary the unions argue is insufficient to cover the cost of housing in California, especially in the expensive rental markets where UC campuses are located. The poverty line in California is $36,900 for a family of four, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Some graduate student workers take on jobs outside the university, even though the university prohibits additional work. The UC also argues graduate student workers are part-time, officially working 20 hours a week. Graduate students contend their research and teaching work add up to a full-time schedule.

In its latest offer, the UC office of the President proposed raises of around 26% across three years for most graduate students working as teaching assistants, tutors and instructors, in addition to pay bumps based on experience. The system said its latest offer would result in minimum salaries of $29,000 to $36,000 by fall 2024. The UC’s offer for the union on strike representing graduate student researchers would set a minimum pay of $33,500 to $48,500 by fall 2024.

The two sides are now beginning to meet with a mediator, current mayor of Sacramento Darrell Steinberg, to resolve the impasse. Steinberg helped settle another labor dispute in California this fall.

The UC and the unions have agreed on some workplace issues and benefits, such as maternity leave, transit passes and anti-bullying protections. Two other bargaining teams, representing 12,000 academic workers, ratified their contracts with the UC last week and returned to work.

So far the UC has been paying the striking academic workers during their work stoppage, but the unions say that may soon end.

The actions are proposed by local members, not the statewide union leadership, said Jaime, who makes $27,000 during the academic year through UCLA and pays $1,200 a month for his split of the rent and utilities for an apartment he shares with roommates.

Marshall, a UCLA academic worker who uses they/them pronouns, said they took part in a union-provided training on civil disobedience. The training taught Marshall how police order protesters to disperse, the process for an arrest and other worthwhile details, including that those jailed may not have access to prescription medicine or tampons.

From that training, Marshall and others agreed they’d generally comply with police during their protest at The David Geffen Company, but would refuse to leave. That group buy-in is important, Marshall said, because if one member provokes a police officer, other members could receive rougher treatment. Ultimately, Marshall and their striking colleagues were arrested for failure to disperse.

Marshall, a third-year graduate student worker in social psychology who earns $30,000 a year, manages a small WhatsApp group chat to plan acts of civil disobedience in Los Angeles. Marshall jokingly named it “totally spies” on their phone — a nod to an early 2000s animated show. The group researches what to expect at a protest site, exit strategies, whether there’s security personnel and how many strikers should take part in a given location, among other considerations.

The university wouldn’t say if the protests are influencing its bargaining position. “Though the University respects the right of those on strike to peacefully protest, the activity is not a factor at the bargaining table,” wrote Brent Colburn, senior vice president of external relations and communications at the UC, in an email.

The university is also critical of tactics that target UC officials’ homes and businesses. “While we fully support protestors’ right to express their grievances through legal means, we believe that disruptions that fall outside of the law at private businesses or homes are inappropriate and uncalled for,” wrote Roqua Montez, a spokesperson for the UC Office of the President.

Sures, the UC regent whose home the graduate student workers gathered in front of last week, said that no one from the unions reached out to talk to him first. He was home the day union members arrived, he said.

Support from other unions

California’s strong labor presence has helped the striking graduate student workers. The California Federation of Labor, representing 1,200 unions and 2 million workers, allowed its members to withhold their labor in solidarity with the UC students.

Desmond Fonseca, a UCLA graduate student worker studying history, described an early morning when he and others on strike began picketing a campus construction site. Some of the unionized construction workers walked off the job. Grad student workers at UCLA have picketed delivery sites at the campus, prompting some drivers represented by the Teamsters union to turn around without ever dropping off shipments UCLA ordered, including sodas and parcels for research labs, Fonseca said.

Some unionized workers unaffiliated with the graduate workers have honored the picket line, confirmed Elizabeth Strater, communications director for the labor federation.

“When you have this kind of comprehensive solidarity, you are going to have a death of 1,000 logistical cuts keeping your operations running the way you’re used to,” Strater said.

Some graduate student workers are attempting to attract more undergraduate students to their cause. One approach is a petition to have the UC distribute partial tuition reimbursements to undergraduate students affected by the strike. So far around 3,300 presumed undergraduates have signed the petition.

“The purpose of a strike is to put pressure on the employer. However, as it stands, UC administrations have nothing to lose,” the petition reads. “Students pay the same tuition regardless of how much time and learning we lose if a strike occurs.”

Aly Fritzmann, a UCLA graduate student researcher in atmospheric and oceanic science helping to organize the signature-gathering, said she feels for the undergraduate students who for weeks were enrolled in courses without teaching assistants providing lessons, grades or feedback on their assignments.

“Students did miss out on their education that they paid for and anticipated,” Fritzmann said.

Supporting partial tuition reimbursement for undergraduates is also “an expansion of our strike efforts and increasing our solidarity,” she said. Attracting more undergraduates to the union’s cause could help fill the chasm left by the 12,000 academic workers who agreed to new contracts last week and now can no longer strike.

Fritzmann prefers this strategy to the direct actions targeting UC leaders, including the UC regents. “It didn’t really seem like … targeting their spaces directly was the best use of all of our times,” said Fritzmann, who took part in the events targeting Sures. Still, she added that with 36,000 striking members, there are many simultaneous approaches graduate student workers can pursue to pressure the UC.

On the final day of the fall term at UCLA last Friday, when many graduate students left home for the holidays, Marshall and about a half dozen other grad workers partially blocked the entry into the campus office where professors run their students’ multiple choice exam responses through a grading machine.

With a laugh, Marshall said: “We called the Scantron machine a scab.”